A man and a woman from a major corporation had visited Rebecca’s school: the same corporation that had underwritten the new wing of the gymnasium, which now bore the corporation’s name. In honor of the cooperation with the school, the man and the woman had promised the students promotional gifts they could claim by becoming fans of the company in the social media everyone Rebecca’s age had switched to this year. Rebecca had joined the fan base, and she’d received shampoo, conditioner, and hairspray in the mail, along with a drug called ALTIUS! For “pressure-induced interaction deficiencies” and “situational stress,” and an experience device–the iAm.

The iAm device, this phone that wasn’t a phone, was a mini “UI-free” viewing device. The unit Rebecca had received was still a prototype, but an improved version would be coming to the market this fall.

You could use the device to browse the internet, watch videos, listen to music. But there was no UI to speak of, as the company explained in the user guide: the experiences were transmitted via a few small, stylishly designed electrodes directly to the auditory and visual cortex. You still needed the sensory terminals in the cortex but you didn’t need the sensory cells, the experiences but not the outside world–just the device.

Apparently the user experience was still a little choppy at times. According to Rebecca, things appeared in double or disappeared completely pretty often, and the sound could randomly muffle in a weird way. But the feel was supposed to improve the more you used the device. Every detail–like where, what, and how Rebecca watched and how her brain reacted to it–was apparently registered directly with the device manufacturer without any need for separate action. This meant the manufacturer could fix problems and upload new updates in real time. They could also automatically send Rebecca links, movies, and music customized just for her without any requests or unnecessary fiddling with the settings.

To say the man and the woman had been enthusiastic about the device was a gross understatement. For Rebecca, the coolest thing was being able to watch and listen to whatever she wanted while she was in class or eating dinner. You didn’t have to face any particular direction, like you did with a dedicated screen, because movies and written text appeared in front of your eyes when you focused on them. If you wanted to, you could also look right through them; it wasn’t like the rest of the world went anywhere. So you could read your emails while you were strolling down the street, watch movies while you were jogging! Whatever you wanted wherever you wanted! Without a screen or monitor. Within certain limitations, you could change programs and volume by power of thought. Calibrating the commands took some time and wasn’t always perfect, a little like speech recognition in the early stages.

“What sense does that make?” her father Joe had asked. “There’s no way you can concentrate on what’s going on here if you’re watching a movie at the same time!”

Rebecca rolled her eyes. “I’m sure I’m missing out on a ton.”

“Listen, Becca,” Joe said. “About that medication ALTIUS! your ‘friends’ gave you. I believe you when you say you haven’t taken it. But there’s something about it I’d still like to…

He considered how to continue. He didn’t want to be too controlling or, on the other hand, frighten her too badly.

“I did a little looking into what’s known about it.”

“Ooh, world-famous innovator Joseph Chayefski is on a mission to deconstruct. Stock prices collapse.”

“It was developed to treat autism.”

“Hm.”

“From what I can understand.”

“Hm,” Rebecca said again. She frowned at him as if she were deep in thought. The expression on her face encouraged Joe to continue.

“I’m not sure it’s a good idea to interfere with the brain’s neurochemistry using a substance like that. To be perfectly frank, I’m worried. I’m not convinced its long-term effects have been researched properly.”

He said that he’d spent several days reading studies, trying to figure out what was known about the operating mechanism of the new neurochemical. But the studies that had been published were commissioned by pharmaceutical companies, and companies structured tests in a way that was beneficial to their products, misrepresented results, and left negative results unpublished. Positive results, on the other hand, they published over and over again.

Joe had called the Federal Drug Administration, which had granted marketing permission for the drug – aside from autism, solely for a psychological disorder Joe had never heard of, pressure-induced attention deficiencies in social interaction. But he hadn’t been able to get anything out of the person he spoke with except a list of the steps it would take to acquire copies of all the test results registered with the administration, including those that had never been published. It was possible, in theory, but it would take a while. And would demand substantial investigation into a field of research that he, to be honest, knew nothing about. Furthermore, a colleague had told him that senior authorities in the drug administration were often the former big pharma CEOs and vice versa, and that some members of the panels evaluating the safety of drugs received compensation from the pharmaceutical companies.

He sighed.

“Becca, no one knows what the long-term effects of interfering with brain function that way could be. Apparently it changes the way cell membranes work, and it might affect transporters, too, but… Does it matter? How will that affect the brain? Tomorrow? Next year? Ten years from now?”

Rebecca was staring straight ahead, looking thoughtful. Her smooth, perfect forehead was wrinkled. Joe felt a pang of tenderness. For once he had managed to keep his dear daughter’s attention, for once his expertise meant something to his critical, intelligent girl-for once he got to be a dad, one his daughter found worthy of her undivided attention.

“We don’t know,” Joe continued, more tenderly. “We really don’t know. No one knows. Ask any expert, Becca, and the honest answer is that no one knows. We would need independent, real studies, but they don’t exist yet. Of course everything looks great in the pharma companies’ own tests, because they purposely conceal all the problems. That’s not science, it’s just marketing that looks like science.”

Rebecca looked at him for a long time. Just when he thought she wasn’t listening, Rebecca nodded. Something about her expression was a little off.

“So could we make a deal that you won’t take that chemical before you talk to us? Before we’ve had time to investigate what’s known about it?”

From the look on Rebecca’s face, which appeared to roam at the frontiers of confusion, uncertainty, and affection, Joe got the impression he was giving the pharma companies a drubbing.

“Your mom agrees with me,” Joe added. “She’s really worried about this, too.”

Rebecca stared at him as if she didn’t understand what he was saying.

“So could we?”

“What?”

“So could we make a deal? Now. Shake on it.” Joe held out his hand.

“What?” Rebecca snapped and plucked the electrodes from her hair, looking irritated. Apparently she had put them back on without Joe’s noticing.

Oh, hell, no.

“What? What?”

“Did you have those electrodes on this entire time?”

“Excuse the fuck out of me.”

“Didn’t you hear a damned word of what I just said? I’ve been talking for the last half hour!”

“I told you I was watching a movie!”

Hell no. Hell no.

“Besides, they’re not fucking electrodes! They’re paws! And if you’re done talking now, I’d like to finish watching this movie.”

__________________________________

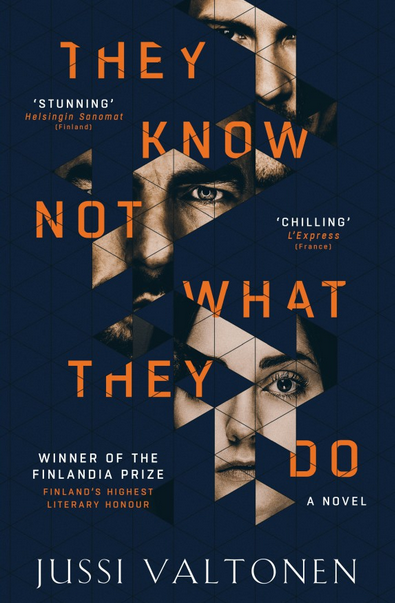

From THEY KNOW NOT WHAT THEY DO. Used with permission of Oneworld Publications. Copyright © 2017 by Jussi Valtonen.