The Writers Vincent van Gogh Loved, From Charles Dickens to Harriet Beecher Stowe

6 Books Essential to Our Understanding of the Artist

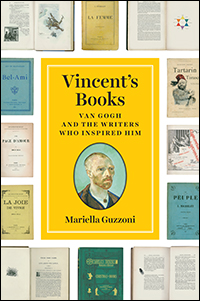

Vincent van Gogh’s art is known even in remote corners of the world, but his dramatic life story has often obscured the richness and complexity of his work. In Vincent’s Books I attempt to tell this story anew by considering the books he loved and showing the crucial role literature played in his life and work.

Vincent was an avid and multilingual reader, a man who could not do without books. In his brief life he devoured hundreds of them in four languages, spanning centuries of art and literature. Throughout his life, his reading habits reflected his various personae—art dealer, preacher, painter—and were informed by his desire to learn, discuss, and find his own way to be of service to humanity.

Which books were among the dearest to him? I have chosen six that can tell us something about a “new” Vincent, the real man behind the often-exploited scenes of his life. This Vincent is a far-cry from the impulsive artist he has frequently been depicted as.

Let’s take a stroll through these books: an exercise in “anti-mythologizing.”

*

Jules Michelet (1798–1874), Histoire de la Révolution française(1847–1853), 9 vols, Paris: Le Vasseur, Nouvelle Édition, Préface de 1868

Jules Michelet (1798–1874), Histoire de la Révolution française(1847–1853), 9 vols, Paris: Le Vasseur, Nouvelle Édition, Préface de 1868

June 1880: “Good—now I no longer have those surroundings—however, that something that’s called soul, they claim that it never dies and that it lives for ever and seeks for ever and for ever and for evermore. So instead of succumbing to homesickness, I said to myself, one’s country or native land is everywhere. So instead of giving way to despair, I took the way of active melancholy as long as I had strength for activity, or in other words, I preferred the melancholy that hopes and aspires and searches to the one that despairs, mournful and stagnant. So I studied the books I had to hand rather seriously, such as the Bible and Michelet’s La révolution Française, and then last winter, Shakespeare and a little V. Hugo and Dickens and Beecher Stowe…”

Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811–1896), Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life among the Lowly (1851–1852), London: Routledge & Sons, c.1880

Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811–1896), Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life among the Lowly (1851–1852), London: Routledge & Sons, c.1880

Vincent, 27, is in the mining region of the Borinage, in Belgium. For a year and a half he has been among the miners, seeking to console the workers of the underworld. He is at a dead end. He cuts himself off from the world, and immerses himself in reading.

Two books were crucial in what was to become the period of his rebirth as an artist: Histoire de la révolution française (History of the French Revolution, in 9 volumes), by the greatest of the French romantic historians, Jules Michelet, and Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, the novel that helped foment anti-slavery sentiment in the United States and abroad.

Michelet’s new approach to writing history dared to give the People agency, placing them firmly at the center of the revolutionary dynamic. Vincent, too, would put the faces of the People at the center of his revolution in portraiture. Michelet himself described Beecher Stowe as “the woman who wrote the greatest success of the time, translated into every language and read around the world, having become the Gospel of liberty for a race.”

What are the common themes? The fight for freedom and independence; the moral importance of literature; the plight of the poor and deprived. Both books were modern gospels for Vincent in a moment of great doubt, when he rejected the “established religious system.”

“Take Michelet and Beecher Stowe, they don’t say, the gospel is no longer valid, but they help us to understand how applicable is it in this day and age, in this life of ours, for you, for instance, and for me…”

Alfred Sensier (1815–1877),La Vie et l’œuvre de J.-F.Millet, Paris: Quantin, 1881

Alfred Sensier (1815–1877),La Vie et l’œuvre de J.-F.Millet, Paris: Quantin, 1881

March 1882: “Listen, Theo, what a man that Millet was! I have the big work by Sensier on loan from De Bock. It interests me so much that I wake up at night and light the lamp and go on reading. […] Here you have a few words that struck me and moved me in Sensier’s Millet, sayings of Millet. Art is a battle—you have to put your whole life into art.”

Vincent is living in The Hague. He is moved by the words of Jean-François Millet, as reported in La Vie et l’œuvre de J.-F. Millet, which the writer Alfred Sensier dedicated to the French realist painter of peasant life. Millet’s melancholic character is a revelation for Vincent, a mirror in which he recognizes many aspects of himself. His devotion to “Père Millet” soon compels him to set an ambitious work schedule focused on peasant painting.

Guy de Maupassant (1850–1891), Bel-Ami, Paris: Victor-Havard, 1885

Guy de Maupassant (1850–1891), Bel-Ami, Paris: Victor-Havard, 1885

October 1887: “Like me, for instance, who can count so many years in my life when I completely lost all inclination to laugh, leaving aside whether or not this was my own fault, I for one need above all just to have a good laugh. I found that in Guy de Maupassant…”

Vincent wrote to his sister Willemien from Paris, referring to Maupassant’s “masterpiece,” Bel-Ami, a book that takes center stage in Van Gogh’s own Still life with plaster statuette (Stilleven met gipsbeeldje, 1887). Vincent gives his “little” sister advice on reading, suggesting some of the most prominent French naturalist authors like Émile Zola, Edmond De Goncourt, and Guy de Maupassant, whose work he had gathered in Piles of French Novels.

Maupassant’s Bel Ami is the nickname of protagonist George Duroy, who is very popular with the women of the beau-monde in Paris.He uses his success to climb the social ladder. From Arles, Vincent writes jokingly to his brother Theo “I’m not enough of a Bel Ami for that,” referring to his struggle to convince the women of Provence to sit for him.

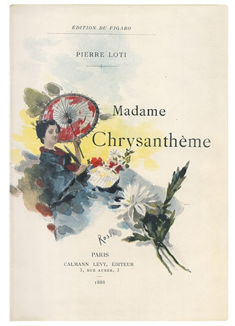

Pierre Loti (1850–1923), Madame Chrysanthème, Paris: Édition du Figaro, Calmann-Lévy, 1888

Pierre Loti (1850–1923), Madame Chrysanthème, Paris: Édition du Figaro, Calmann-Lévy, 1888

June 1888: “I’ve just read Pierre Loti’s Madame Chrysanthème; it provides interesting remarks on Japan…”

Vincent writes from Provence to Émile Bernard, the painter friend he had left behind in Paris, where a wave of Japan-mania was gripping art circles.

Loti’s dramatic romance (which inspired Puccini’s Madama Butterfly) is set in Nagasaki and tells the story of a French official who marries a Japanese woman. For Vincent, Provence was “his Japan” and Madame Chrysanthème inspired him deeply—one only has to look at the most striking of his self-portraits, Self-Portrait Dedicated to Paul Gauguin (1888). The artist’s eyes take on an almond shape. Vincent paints himself like a Japanese monk, “a simple worshipper of the eternal Buddha”.

Charles Dickens (1812–1870), The Works of Charles Dickens. Christmas Books, Household Edition, London: Chapman & Hall, 1878

Charles Dickens (1812–1870), The Works of Charles Dickens. Christmas Books, Household Edition, London: Chapman & Hall, 1878

April 1889: “These last few days I’ve been reading Dickens’s Contes de Noël, in which there are things so profound that one must re-read them often…”

In the darkest moments of his life—self-exiled in the asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence—Vincent finds consolation in Charles Dickens, his favorite British author, “one of those whose characters are resurrections….” In the spring of 1889 he goes back to Dickens’s Christmas Books and Beecher Stowe’s novel. These two old friends, whose landmark works Vincent unites in one of his portraits, now offer him positivity and humanitarian sentiments. The ethical and political potential of (literary) art, both in Dickens and in Beecher Stowe, flows naturally in their fiction as examples of clear moral commitment. Art for mankind, Vincent’s artistic credo.

Much has been written about Vincent’s astounding artistic evolution, over a period of just ten years. In his passion for books lies part of the energy and creative tension that flows through his art. Faithful friends, sources of inspiration and consolation, safe harbors in rough seas—for Vincent books were all this and more. It is great lesson for us, too, to bring joy in these difficult times.

__________________________________

Mariella Guzzoni’s latest, Vincent’s Books, is available now.

Mariella Guzzoni

Mariella Guzzoni is an independent scholar and art curator living in Bergamo, Italy. Over many years, she has collected editions of the books that Vincent van Gogh read and loved.