Before we begin talking about her book, Tori Amos wants to know how I’m doing. “How are you and where are you?” she asks a second time, after I shyly deferred her first inquiry.

I tell her I’m calling from New York, a city on quarantine from the novel coronavirus pandemic, where at all hours sirens shatter the silence of empty streets. “New York is in my thoughts,” she tells me. “If anyone can get through this, New Yorkers can. You have the resilience.”

And Tori Amos knows about resilience. It’s a theme of her new book, Resistance: A Songwriter’s Story of Hope, Change, and Courage. Like any one of Amos’s 15 albums, the book is difficult to pin down stylistically. It is in part memoir, going from Amos’s start on the stage as a young teen playing piano bars in Georgetown in the late 70s and early 80s, to the death of her beloved mother, Mary, just under a year ago. It is in part an extensive critique of patriarchal power built on personal experience, the many stories she’s heard from her fans over the years, and her impressive command of geopolitics.

And, at the same time, it’s an exploration of process, as she essentially pops open her piano and shows us her strings, the work and imagination required to bring “Tori Amos” to life on stage and record. All of this is structured around a backbone of verse, with the chapters of prose bracketed by song lyrics.

Displayed on the page, the poetry of her songwriting shines. Amos said this decision came to her one night over dinner with a friend. “She said to me, ‘I have no idea what your songs mean, because I can’t hear the music and the lyrics together and understand what you’re talking about. So can you just read the words to me?’ After a bottle and a half of very good Bordeaux I finally said, ‘I’ve never done that before, but okay, pick a song.’”

As she recited the lyrics, her friend began to cry. Amos was struck by how her words had a different meaning in this context, offering a new point of entry for a listener. That portal worked for her as a writer as well. The songs operated as a time machine, bringing her back to past crises, both personal and political. “I’d look at the songs and say, ‘Take me back, “Silent All These Years,” to when Anita Hill was on the stand. Take me, “Ophelia,” to when Dr. Ford testified against Brett Kavanaugh.’”

The lyrics lend a thematic cohesion as the book jumps around her life in not-quite-chronological order. As a reader, you’re never lost, because—just like for the author—the songs lead the way.

*

Amos is speaking to me over the phone from her home in Cornwall, England, where she’s socially distancing with her husband, Mark Hawley, a producer and sound engineer, and their 19-year-old daughter Tash. It’s farm country. “Most days, I see more animals than human beings.”

The barn in the backyard houses Martian Engineering, her recording studio, where she’s working on a new album. “I’m writing towards what people are feeling, because there are so many triggers right now—grief, loss of freedoms, and anxiety as we wonder, when the virus is contained, will all those freedoms come back? It’s pushing me to write a different record then the one I was writing.”

Resistance was inspired by a moment of political crisis as well: the election of Donald Trump in 2016. A year later, Amos toured the country in support of her album Native Invader. While backstage at the Beacon theater in New York, Rakesh Satyal, the editor of her previous book, Tori Amos: Piece by Piece (co-written with the music journalist Ann Powers), suggested she write about the value of being an artist at a time when the country felt perilously close to losing its democracy. “I said okay, not realizing this would be the most challenging thing I’ve ever done.”

Amos spent a year-and-a-half writing Resistance. Then, in May of 2019, her mother died after having suffered a stroke two years prior. “It was cruel, what that vicious stroke did to her. Because it was her greatest fear. Her mother had a stroke and was in a nursing home for two years, and my mother would visit her and say, ‘If this ever happens to me, you have to find a way to let me off this planet.’ But I did not have the courage to do that.”

After a pause, she continues, “People tell you they’ve lost their mother and you think you understand because you lost someone you cared about too, but I don’t know if anyone really knows how they are going to handle grief. It’s different when it happens, different for everyone.”

She wrote into those feelings, describing how the aftermath of her mother’s death left her depressed, sitting in a broken rocking chair, unable to do anything except commune with Mary in memories. Like a ghost out of A Christmas Carol, Mary takes her daughter from scene to scene in her life. There’s a rawness to these moments that’s as powerful and moving as anything Amos has put to music, an immediacy and vulnerability to her storytelling and the dynamic between the spectral mother and distressed daughter in dialogue.

Writing these chapters provided the key that unlocked Resistance for her. “When my editor read them, he called and said, ‘I think you found the voice for the book in these chapters. Now you need to rewrite the rest of it.’ And he was right—I had tried so hard, but the book did not have heart. I couldn’t get there until grief cracked me wide open.”

“Being a good editor is not about saying yes. Sometimes it’s about saying, you don’t have it. So as a writer, you have to begin again—and you know, you should want to. But still, you also want to pull your hair out.”

Over the course of a busy three months, Amos rewrote the book entirely.

*

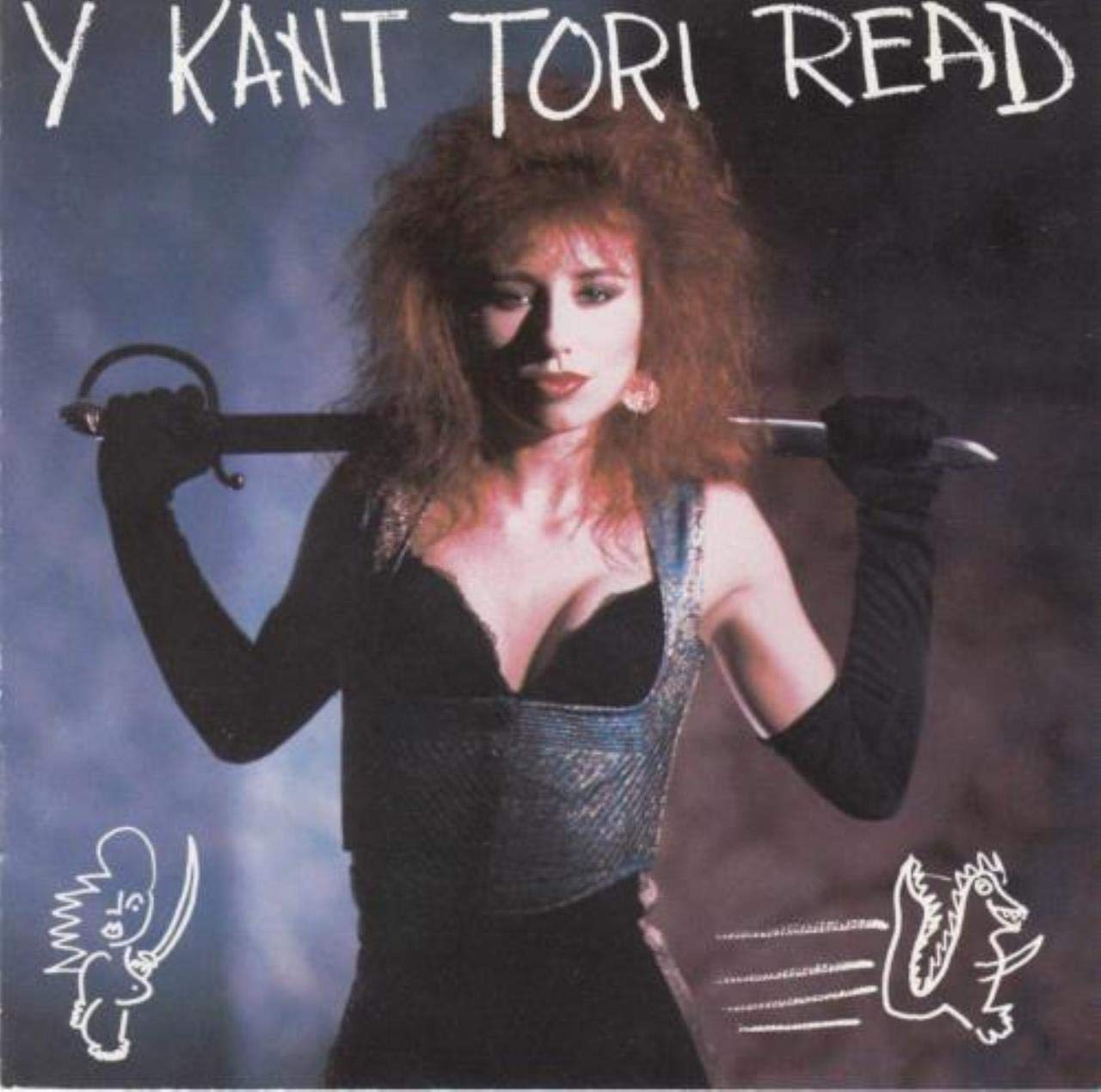

At the age of five, Amos was the youngest student ever admitted to Baltimore’s Peabody Conservatory, with a full scholarship and a repertoire of about 200 songs. She could play by ear songs she had heard only once. But at eleven, Peabody rescinded the scholarship and asked her to leave, in part because Amos refused to read sheet music. This incident gave name to her first commercial project, the band Y Kant Tori Read, which released one self-titled album in 1988. At the time, Amos was 25, and had been living in LA for about four years, trying to break into the pop scene.

“Being a good editor is not about saying yes. Sometimes it’s about saying, you don’t have it. So as a writer, you have to begin again.”Looking back on that album cover is like glimpsing an alternative universe, with Amos’s red hair teased and permed, a sword held behind her head, chest thrust forward in a push-up corset—a look manufactured to appeal to young male fans of hair metal. The album failed to spawn a hit song. Amos hopes Resistance speaks to artists like the one she was at the time, trying to find their voice, and feeling pressure—both internal and external—to be something they’re not, chasing commercial fame.

Without casting any shade, she says that’s just not the kind of songwriter she is. Though the lesson wasn’t an easy one for her to learn.

“The world did not miss a beat when my first record bombed, but it practically destroyed a part of me. And the disappointment for my father? It’s like, how do you go from child prodigy to bimbo? That took me down. I mean, I was on the floor.”

It’s true, she says, some artists find their voice young, and some know exactly what style they want to work in. But for her, it was harder. In the Georgetown piano bars, she could go from playing a military style march to a Dolly Parton and Kenny Rogers duet to a Led Zeppelin track. But that was performing, not creating. “Songwriting requires a very different set of skills than performing, but it took the failure of Y Kant Tori Read to teach me that.”

And it also required years of struggle, during which record executives heard demos of now classic songs and told her to replace the piano with guitars. Feeling like she had already betrayed her instrument with Y Kant Tori Read, she refused. Though it took more than two years to make, the resulting album, 1992’s Little Earthquakes, features her on the jacket looking like the iconic Tori Amos we know—clad in a blue jumpsuit, red hair relaxed, literally a giant next to a toy piano, poised to step forth from a box. In every album to follow, she’d be just as in control of her messaging; the lyrics, sound, and imagery all work in tune, telling a tale.

“Putting together a list of songs to create a narrative was something I cut my teeth on in those piano bars,” she tells me. And for Amos, a big part of storytelling is listening. “I toured Little Earthquakes alone, allowing the audience to collaborate in the show. Ever since, on the road, I try to have a meet and greet with fans; if I can’t, then they give me letters. So the set list will reflect what’s happening in Chicago, say, for that week and that audience, or what’s happening in Berlin. Sometimes, right before I walk on stage, I feel the audience’s energy through the curtain and I’ll decide to swap out one song for another. It’s a conversation, and the audience is very involved.”

Creatively, writing the book required a different, more solitary kind of work and analysis. “I’m trying to explain my process instead of living the process,” she says. “The songs are the magic.”

*

Throughout Resistance runs the idea that the artist exists to serve; not just her audience, but the creative force that speaks through her, The Muses. “There are some people who think that they write their songs, and you know what, maybe they do,” Amos says. “But I don’t. I co-create.”

The Muses gift her with bits and pieces of a song—“usually only eight bars at a time”—and she works with that to develop the whole. Her writing process, as she describes it in the book, involves travel and research, word maps and free association, and most of all, listening, paying close heed to people oppressed, and critical attention to those in power. This too grew out of her time in the piano bar, when she witnessed senators sharing drinks and handshakes with lobbyists, Big Oil, and corporations.

“The Muses are quite something,” she tells me. “They’ve been with me since I was a tiny little girl, and they are real. Even my husband, who is a cynic, and an agonistic—he doesn’t believe in things unless they make sense—has seen it happen. I’ll be ready to record a song that’s written and all of a sudden something I’ve never heard before comes out. For example, “Marianne,” on the album Boys for Pele, was written as you hear it on the record. And I feel I’ve never really learned how to play it properly, because when a song just downloads like that, I’m left thinking, ‘What in the world was that?’”

Under The Muses’s influence, Amos develops a Song Being, a musical form with its own soul and essence. The relationship she forges with that Being is personal and intense. Handing them off to the label, at the end of the recording process, is tough for her, and she marks it with a glass of champagne or, “when I really need it,” tequila, and a few hours alone in the studio.

“It’s not a private conversation once they leave the control room.” The Muses, she says, have made clear to her: she doesn’t own the songs or control what they mean. “What somebody thinks of a song is just as valid as what I think of it. You have to accept that, I think, as an artist.”

And yet, when I ask her about her feelings now, right before the book’s release, she expresses trepidation. Though she’s 56 years old and has been creating music professionally almost her whole life, publishing a book feels different, perhaps because there is no co-creator this time around. “Like it or hate it, you have to point the finger at me, because I wrote it.”

She’s curious to hear what people find in the book, what messages speak to them, what meanings they take from it. For now, she’s back in the process, weaving melodies, a vessel for The Muses. But she is, as always, listening.