“The Wines Tasted Alive.” Visiting an Icon of Natural Winemaking in Slovenia

Rachel Signer on an Afternoon with Saša Radikon

We arrived to spectacular views of the snow-capped Alps. As we wandered between hotels, trying to find a vacancy, I noticed various signposts referencing Ernest Hemingway, who apparently had written much of A Farewell to Arms in Kobarid, surrounded by the front lines where thousands of men had died in the Battle of Caporetto, a decisive moment in World War I when the Austro-Hungarian forces pushed back the Italians.

I found a wrinkled, barely acceptable dress to wear—I hadn’t had time to do laundry during my weekend in Paris. Wildman and Tom put on, to, my surprise, collared shirts. We made our way to dinner after what had turned out to be a long day and upon sitting down at one of the outdoor tables, we immediately asked for some natural wine. The young, clean-shaven sommelier went away and returned with a funny shaped, clear bottle. It was narrow on top, bulbous and large on bottom. “This is a Chardonnay from a very respected producer here, called Batič,” the sommelier said, pouring for us, adding, “biodynamically farmed.”

We tasted eagerly, smiled broadly, and then as soon as he walked away, began to criticize the wine in unison.

It was biodynamic, which was fantastic for the earth, and a great start in terms of making a natural wine. But, as Wildman put it, “Too much sulfur.” Tom and I agreed. The wine tasted tight and confined, and not living, thanks to the addition of sulfur. Wildman guessed that it had “fifty parts,” meaning fifty parts per million. We politely pushed our glasses to one side and asked the bewildered sommelier, who had expected us to love the wine, for “something really crazy.”

We wound up with a bottle of Franco Terpin’s Sauvignon Blanc, shaded bright orange from extended skin contact during fermentation. It had strong aromas of fresh peaches and clementines, and more important, it had edginess—it was so alive, it even seemed like it was on the brink of being faulty. It was made without any sulfur.

Franco Terpin wasn’t technically a Slovenian winemaker—he was based just over the border in Friuli, in a village called Collio, which historically was deeply connected to Slovenia, and only part of Italy since 1945, when Slovenia joined Yugoslavia.

“He’s near Saša, I think,” said Tom to Wildman, who nodded.

“Saša… as in, Radikon?” I asked. Tom nodded and explained that they had met Saša Radikon, a famous natural winemaker, at a festival called Rootstock in Sydney a year or two earlier. His wines had been an early inspiration for the two of them. “Sam showed them to us,” explained Tom. I didn’t know yet who Sam was, although the mention of his name seemed to trigger sadness in Wildman and Tom. But I definitely knew about Radikon. When Tom suggested we try to visit him during our time in Slovenia, I wholeheartedly agreed. In the world of natural wine, there are a few names that inspire absolute reverence; Radikon is one of them. In New York, these highly allocated, mostly skin-contact white wines are difficult to come across and expensive to enjoy. A Radikon bottle was striking in that it came in two unique sizes, either 500 mL or 1 L as opposed to 750 mL. But despite the great branding, Radikon wines weren’t just status symbols. They were completely unique in taste. A glass of Radikon was powerful, electric energy.

We finished our lengthy meal with a fragrant dessert—crumbly walnut cake with cow’s milk kefir and pollen ice cream, alongside pear poached in chamomile and drizzled with local honey—then drove through the dark to the little hotel in Kobarid and slept.

*

The world was spinning, inside my head. My gut was spinning, in the backseat of the Fiat 500. The guys chatted happily in the front, while Tom drove like a true Italian, taking the curves at breakneck speed. One moment, we were in Slovenia, the next, a road sign told us we’d passed into Italy. Then around the next bend, back to Slovenia—and so on. I no longer saw the natural beauty around me—I only concentrated on holding in my breakfast.

We were late to visit Saša Radikon, because Wildman had decided to stop and chat with the owner of Hiša Franko earlier that day, and then we’d all gone for a quick skinny dip in the river. Now we were rocketing through the hills—incidentally, collio is Italian for “hilly”—at the expense of my personal equilibrium.

We arrived in Oslavje, the valley where the Radikon family’s home, vineyard, and winery has stood for several generations, and Tom and Wildman lifted themselves out of the Fiat 500. We’d driven with the top down, and Tom had wisely pulled his long locks into a bun, but Wildman’s hair was sticking straight up. I opened the door and spilled out onto the grass, where I lay belly-up for the next twenty minutes, taking deep breaths.

Once I recovered, I followed the voices until I found Tom and Wildman standing with the larger-than-life Saša, just outside the winery. Saša, this icon of natural winemaking, paused to look at me from his height of six feet. “I’ll be right back, I’ll just ask my mother to bring you some of our grappa,” he said in a booming voice. “Then you’ll feel better.”

We headed underground to the winery, where large, wooden fermenters filled the cramped space in which the famed Radikon wines are made. Saša explained the winemaking approach, most of which he’d inherited from his father, Stanko: three to six months of maceration on the skins for the white wines, then around two years of aging before bottling. Finally, Saša’s mother, Suzana Radikon, appeared with a small glass of strong grappa, which I swallowed. The dark cellar came into focus, and my headache began to subside.

The wines tasted alive, as vibrant as the Merlot just entering veraison just below us on the hill.

It is sometimes said about natural wine that “the wine makes itself,” or that “nonintervention” means doing nothing. Nobody thinks wine makes itself. What is meant by the term “natural wine” is that nobody forces fermentation to happen by adding yeasts, no sugar is added to boost alcohol, no flavor or color adulterants are used, no filtration is applied, and no fancy “reverse osmosis” machines are deployed to engineer the wine. All of those practices are quite common, in commercial and even boutique wineries. At Radikon, by contrast, only organically farmed grapes and, sometimes, small doses of sulfur went into the wine, and the techniques were hardly modern.

This approach originated with Saša’s father, Stanislaus, known as “Stanko”—a man whom I’d heard spoken about in tones of reverence amongst the previous generation of natural wine professionals in New York. In the 1990s, Stanko was part of a group of pioneering winemakers from the Italy-Slovenia nexus who decided not to pursue the conventional winemaking that was all-the-rage and instead committed themselves to old-fashioned techniques, organic farming, and minimal or no sulfur additions. Radikon was (and still is) often spoken about alongside another now-famous producer, Josko Gravner, known for his exclusive use of Georgian qvevri in the cellar.

Whereas modern white winemaking eschews skin contact and generally relies upon the newly introduced stainless steel tank for fermentation—think of a sharply acidic Italian Pinot Grigio for reference—Radikon and Gravner embraced these antiquated forms of winemaking. In an “aha moment” that for Stanko began with the area’s native grape, called Ribolla Gialla, it was found that leaving white grapes on their skins for months at a time before pressing delivered an entirely different wine. As Saša recounted for us, Stanko had loved the strong aromas, bright orange hue, and rich texture of the skin-macerated Ribolla Gialla, and soon all the Radikon estate white wines were made this way.

The large open-top oak fermenters in the cellar around us were used during this skin contact phase, Saša explained. “The grapes get destemmed, and we punch down the cap a few times each day during fermentation,” he added. It was a simple wine cellar, but it produced some of the most exciting wines I knew, and not everybody was invited to view with Saša himself.

“Your wines, and your father’s wines, they showed us that sulfur-free winemaking was possible,” said Tom, laying his admiration bare.

In 2016, when Stanko passed away from cancer, his loss was felt in New York and other natural wine capitals. By then, Saša had already been working alongside Stanko for several years and had even debuted a new line of wines, one featuring Pinot Grigio and a blend called Slatnik, both of which were bottled earlier than most Radikon wines and received a small addition of sulfites. Saša hoped these bottlings would draw in new fans and make the overall Radikon range more approachable and accessible.

After touring the winery, we headed into the newly built tasting room upstairs, to taste from the recent release of bottles, alongside slices of pecorino cheese. The wines tasted alive, as vibrant as the Merlot just entering veraison just below us on the hill.

__________________________________________________

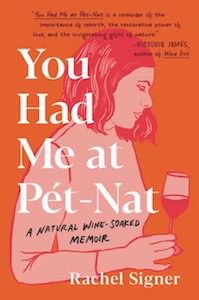

Excerpted from You Had Me at Pét-Nat: A Natural Wine-Soaked Memoir by Rachel Signer. Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Hachette Books. Copyright © 2021 by Rachel Signer.

Rachel Signer

Rachel Signer is the author of YOU HAD ME AT PÉT-NAT: A Natural Wine-Soaked Memoir, and publisher of Pipette Magazine, an independent natural wine-focused print magazine. Originally from the U.S., Rachel lives in Australia with her husband and daughter, making natural wine under the labels Lucy M and Persephone.