“Ghosts come out of nowhere, but the dead just come back.” That’s what Lupillo said to me as he squeezed out a sponge. You have to believe massage therapists. They’re the only ones on a team who’ll tell you the truth, the only ones whose sole aspiration is to spray on the analgesic.

Lupillo’s line was the first sign I’d become an outcast. The second was that nobody played any welcome-back tricks on me. I had returned to Estrella Azul, the team where I got my start. If anyone had still cared about me, they would have pissed in my shampoo. That’s how simple the world of soccer is.

“We even held a funeral mass for you!” added Lupillo. I was watching his bald head, shiny as a crystal ball. Yes, they’d held a mass for me where the priest praised my hustle and integrity, virtues death had conferred. Dead men have integrity.

I almost died with the Mexicali Toucans. I’ve seen pictures of people playing soccer in minefields. In any war there are desperate people, desperate enough not to care about losing a foot, as long as they can shoot a ball. Maybe if I went to war I’d think there was nothing more badass than kicking something round, like your enemy’s head. In my heaven, there are no soccer balls. Heaven for strikers is full of them, I guess. But for defensive midfielders, heaven is an empty field where there’s nothing to do and you can finally scratch your nuts, the balls you haven’t been able to touch your whole career.

I almost died with the Mexicali Toucans. I’m saying it again because it’s absurd and I still don’t understand it. I wonder if the bomb was ball-shaped, if it was like the one The Road Runner hands to Wile E. Coyote in the cartoons. A stupid thing to worry about, but I can’t stop.

I spent three days under rubble. They figured I was dead. I was erased from every team’s roster. (Not that many clubs were fighting over me, but I like to think I had to be erased.)

When I woke up, the Toucans had sold their franchise. When the bomb exploded, so did the dream of having a team that close to the United States, on the only field below sea level. There were lots of rumors when the news got out. Almost all of them had to do with narcotrafficking: the Gulf cartel didn’t want the Pacific cartel hijacking its move into soccer.

I didn’t know anything about Mexicali until the triplets walked into my room in Mexico City. I’d fractured my ankle and was sick of watching TV.

“Somebody’s here for you,” said Tere. From her expression, I should have known my three visitors had buzz cuts.

Not just that: they were enormously fat, like sumo wrestlers. Colored tattoos spilled out from under their t-shirts. All three had neatly trimmed goatees.

They set a case of Tecate beer on the bed, as if it was some incredible gift.

“The brewery’s close to the stadium.” That was what they said.

I’ve always liked Tecate beer. Maybe what I like most is the red can with the shield. Still, it wasn’t a great way to start a conversation.

The fat men were weird. Maybe they were insane. They were the board of directors for the Mexicali Toucans, and the brewery was their sponsor.

I asked them their names and they answered like a hip-hop group:

“Triplet A,” “Triplet B,” “Triplet C.”

Could I do business with people like this?

“We like to keep a low profile,” whichever one of them said. “No photos, no box seats, no names. We love soccer.”

“Sorry, but where the fuck is Mexicali?” I asked.

They explained things I’ve never forgotten that possibly weren’t true. In Porfirio Díaz’s day, the Mexicali desert was famous for a platoon of soldiers that disappeared there. They lost their way and all of them died, fried to a crisp. No one could live in that desert. Until the Chinese arrived. They were allowed to stay because everyone was sure they would die. Who could survive 120° heat below sea level? The Chinese.

As they talked, I started to distinguish between them in a strange way. They appeared to have Chinese blood and I could only tell them apart the way most Mexicans differentiate tattooed Chinese people—the one with the dragon, the one with the knife, the one with the bleeding heart.

“Do you like Peking duck?” asked Triplet C.

Then they started talking about money. They mentioned a number and my throat seized up.

I didn’t answer. The triplets were barely thirty years old. Their obesity made them look like radioactive babies from some Chinese sci-fi flick.

“That’s what you’re worth.” Triplet B scratched his beard. “The Toucans really need you.”

“The brewery is backing us.” They gestured to the case on the bed.

At that point, I should have understood they were planning to launder their money with beer. Narcos are so powerful, they’re free to act like narcos. They didn’t need to dress as geography teachers.

Instead of asking for a few days to consider, I asked the question that would be my undoing:

“Are you thinking of hiring any Argentinians?”

“No fucking way!” said Triplet A.

He smiled, and I thought I saw the gleam of a diamond on his incisor.

I had just turned 33, and I had a fractured ankle. I couldn’t afford to turn down this season in the desert. In the match where I broke my bone, I’d scored an own goal. “The Last Sensation of Christ,” wrote some snarky reporter, rejoicing in my martyrdom.

“You’re playing with fire,” Tere told me. I liked that. I liked playing with fire.

She saw things differently. Anyone who was interested in me had to be suspect.

“There are no toucans in Mexicali.”

She kept saying that, day after day, until we stopped talking about toucans and started talking about Argentinians.

I owe Maradona’s country two fractures, sixteen red cards, and one season on the bench, thanks to a coach who accused me of “prioritizing my trauma.” What I didn’t know was I would owe my divorce to the Argentinians, too.

Baldy Díaz played on two teams with me. One of those guys whose head was fat with talk; in interviews, he spoke like he’d just come from breakfast with God.

He had a big mouth, but nothing on him was as big as his cock. You can’t avoid seeing things like that in the locker room. None of this would’ve been important, except Tere knew about it too. About Baldy’s size, I mean. The time she accused me of “playing with fire,” she had just come back from visiting him. Later, I found them in my own bed. It wasn”t the classic situation where the husband arrives home early. “I’ll be home at six,” I told Tere, and at six I found her riding Baldy’s giant cock. It was her way of telling me she didn’t want to go to Mexicali.

We got divorced through the mail, thanks to a lawyer with five gold rings whom the triplets found for me.

On the way to Mexicali, I went through La Rumorosa, a mountain pass where the wind blows so hard it flips trucks. Looking down from the cliffs, I could see the remains of crashed cars at the bottom. I felt a weird kind of peace. A place for things to end. A place to end my career.

I continued as midfielder, but acted more like a fifth defender. I recovered balls at a reasonable rate for the triplets, although more often, I was being recovered from between the opposing team’s legs.

I got used to playing through the pain. Then I got used to the injections. I played on painkillers more often than a normal body should. But my body isn’t normal. It’s a kicked-in lump. When she was feeling for my nerve with the needle, the doctor talked about my calcified flesh, as if I were turning into a wall. I liked that idea: a wall the opposing team smashes into, a wall on which Argentinians crack open their heads.

One of the triplets had a white tiger. Feeding it cost more than my salary. I got on the triplet’s good side when I asked him to pay me the same as his pet.

“I have an orca, too,” he told me. “Which would you rather have, a tiger salary or an orca salary?” He narrowed his mysterious Chinese eyes.

I know nothing about animals. My salary went up, but I never knew which animal it corresponded to.

I liked Mexicali, especially the food. Peking duck, wontons, sweet and sour pork ribs. That’s the traditional food around there. In one of the restaurants, I met Lola. She was working as a waitress. Her parents were Chinese, and she pronounced her name “Lo-l-a.” I liked to sit in front of the electric waterfall painting. I’d watch it until they pulled out the plug. Lola told me a Chinese guy had been hypnotized once, watching the painting. He only woke up when they put a phone playing “Yellow River” to his ear.

“Have you ever heard that song?” Lola asked me. I told her I hadn’t.

“Fancy music, Yangtze music.” Sometimes she’d talk like that. You didn’t know if she was saying two different things, or if the words that came after cancelled out the ones she’d said before.

The hypnotized Chinese guy had worked for the triplets.

“Don’t believe what people say about them,” explained Lola. “They’re not from the Pacific cartel. They work for the other Pacific. Their mafia is from Taiwan.” She said the last part as if it was a really good thing.

After meals, Lola would hand out toys. Little plastic cats with light-up bellies, things like that. They all fell apart ten minutes later.

“The triplets bring the toys,” she told me as I walked out with something broken in my hands. It was very presumptuous of me to think they’d bought my contract with drugs. They’d paid for me with toys that fell apart.

The triplets promised that the Toucans would have no Argentinian players, but one of them took a trip to La Pampa anyway. He came back with a tattoo of Che Guevara. Some people said the wind in Patagonia drove him nuts. Others said he got high on a boat headed to a glacier, fell into the icy water, and was pulled out frozen stiff. Now he wanted everyone to call him Triplet Che.

Part of his craziness was good for the team. He had hired a very rare kind of player for the Toucans, one with more of a future than a past. Patricio Banfield had just turned 22 and was coming from Rosario Central. He kicked the ball like he was advertising shoes. “You gift-wrap yourself,” the trainer told me when Patricio proved he could punt me all over the field.

The only weird thing about Patricio was the way he’d whistle to catch your attention. “It’s a habit from the pueblo,” he’d say. “I like everyone to know where I am.” I got used to recovering balls and hearing his whistle, way off in the distance. I’d shoot hard in that direction. We didn’t perform any miracles, but Patricio scored consistently. A long-suffering ace, trying to shine in a place that only existed because the Chinese had survived the sun.

I don’t like animals, but I was tired of coming home to a silent house, so I bought a parrot. It talked as much as an Argentinian. I offered it to Lola, but she told me, “Parrots bring bad luck.” That was the first sign of what was going to happen. Or maybe not. Maybe the first sign was how good I felt in La Rumorosa, staring at the cars that had gone over the edge. “In soccer, the end comes soon enough,” Lupillo had told me when I was just starting. “That’s not the problem. The problem is it never stops ending. Memories last a lot longer than legs: you’d better make them good.” I was in the desert, ending a career of bad memories, but I wasn’t sad to be there. A place to make my exit, for everything to end and nothing to matter.

I even got used to the parrot. I’d sit with it on the porch of the house. A one-story house with screens in the windows. Across the street, there was a trailer home where a gringo couple lived. For forty years, the husband had sold caramels at Woolworth’s; his pension went further in Mexico. The only way he was going back to the other side was in a coffin. My parrot was going to outlive my neighbors. But none of that upset me. Now it seems sad, but out there I only thought about the sun. How to stop it beating down on me so hard.

One afternoon, I broke open a fortune cookie in Lola’s restaurant. It said, “Follow your star.” Just that.

That afternoon, one of the triplets came out of the restaurant’s kitchen, followed by a cloud of steam. He looked at the fortune cookie and made a prediction: “You’ll go back to Estrella Azul.” Then he walked out of the restaurant very slowly, as if we were hallucinating his movements: a fat, floating ghost. Going back to Estrella Azul seemed like a terrible idea. Maybe that’s why I thought following my star meant being with Lola. I looked at her young, Chinese face; not pretty or ugly, just young and Chinese. She smelled like tea. I proposed we see each other some place else. She didn’t want to. “Your parrot brings bad luck,: she repeated, as if the animal was part of my body, or we were trapped in a legend, and the parrot housed the spirit of her dead Chinese grandfather.

Together with my change, she gave me a little bag with a Chinese character on it.

“It means ‘lots of wind,’” she explained.

I thought about La Rumorosa and this time those crashed cars made me anxious. I remained nervous until Lola turned off the waterfall. I didn’t want to go back there.

I broke up with Lola despite never having been with her. Though, I had liked the team cheerleaders long before that. When I saw them for the first time, I felt as if I had selected each one, but I focused mostly on Nati.

Patricio Banfield paved the way for me and Nati. His girlfriend—a country singer who sang with too much feeling, making Star Wars faces—was Nati’s friend. We started going out, and one morning Nati forgot her little cheerleader shorts at my house. She left them in the kitchenette, next to her bowl of cereal. I looked at the gringos’ trailer through the window, at the parrot’s cage, the honey-colored light of the desert. I finished what Nati had left in the bowl; the best thing I’ve ever eaten.

Another day, while we watched the blood-colored dawn, she told me they were going to sell the whole team. I asked her how she knew. She didn’t answer and I looked her straight in the eye. On the field, there’s nothing worse than looking into the eyes of someone from the opposing team. He can insult and spit on you all match without rousing you, but look directly at him, and your blood starts to boil. That’s what happened to Zidane in Germany. I’m sure of it. The fury in his eyes. They’ve red-carded me for trying to see what my rivals store in there. With Nati, it was different. Her eyes said nothing. Two still coins. I hated being unable to agitate her. She said, “Patricio should stay. If he does, they won’t sell the franchise.”

My friend Patricio was in negotiations with Toltecas, a strong team out of Mexico City that never wins the leagues but goes far enough to buy and sell players. Here, business isn’t about being champions, it’s about making trades.

One day there was no hot water in the locker room, and they told us the triplets were broke. On a different day, they told us the Chinese liked football and wanted to buy the team. Another day they told us the triplets’ enemies didn’t like that the Chinese liked football. Patricio talked with promoters all day long.

One night we went to the Nefertiti to dance, with Patricio and the country singer. I remember it better than my debut in the Premier League. A sarcophagus appeared in the middle of the dance floor, and out of it came a spectacular woman, completely naked. She floated over to Patricio, who was drinking Diet Coke, and pulled him up to dance. I stared intently at the hieroglyphics tattooed on her back, as if I could decipher them. That’s what I was doing when the bomb exploded.

Hours later I opened my eyes and saw a bracelet shaped like a little snake. The woman who’d danced with Patricio had been wearing it. I smelled chemicals. There was a bottle of water near me. I drank desperately, like I do at the end of a match. I tried to move, but pain shot through my right leg. Then I heard a whistle.

I learned from the papers that I was rescued two days after the explosion. I spent a week in the hospital. Nati didn’t visit me. One of her friends told me she’d found a job in Las Vegas.

Maybe Patricio had been the target of the bomb, the crack midfielder showing off and tempted by other teams. Did the triplets need a martyr, or was it someone else trying to fuck them over? The only certain thing was that Patricio had made it out of the explosion unharmed.

While I was in rehab rolling a bottle under my foot, he had started to shine with Toltecas.

The Toucans were sold and my contract was auctioned off for a piddling amount. When Estrella Azul bought me, the papers called it “A Sentimental Recruit.” In the locker room, though, nobody knew I was back because of sentimentality. Here was the star my fortune cookie had promised.

That’s when Lupillo said that ghosts come out of nowhere and the dead just come back. I’d gone to Mexicali to find the end, but as the sportscasters put it, “It’s not over till it’s over.” When can something with no finish line ever come to an end?

I missed the waterfall that never stopped falling. I missed having a crazy board of directors that paid me the same wage as a tiger. I missed the desert where it didn’t matter that there was nobody around to see me. I missed Nati’s hands after they folded something very precisely, then touched my calcified flesh and I felt them, gentle and cold. The best thing about Nati was that I never knew why she was with me. It could have been a horrendous reason, but she never told me what it was.

It took me a while to get back into the rhythm of things. I went to a doctor’s office opposite Gate 6 of Estrella Stadium. I became a fan of electric massages, and then I became a fan of Marta, a dark-skinned girl who touched me with the tips of her fingers more than was strictly necessary, barely grazing me with her long nails. The first time I made love to her, she confessed she was in love with Patricio. That detail had stopped surprising me. Sooner or later, they all asked: “Did he really save your life?”

Yes, Patricio had saved me. He had searched for me in the ruins of the Nefertiti alongside the firefighters, while in Mexico City they were already performing my funeral mass. He was still Argentinian, but even my parrot missed him.

Around that time, people were talking about the triplets. How they were killed with dynamite. They had only identified one, by his Che tattoo. But the other two had also been there. The police knew this because they’d counted the teeth in the rubble. The triplets died next to a warehouse full of contraband Chinese toys.

I remember the day they came to visit me with the case of beer. “We rise like foam,” they’d told me. They were younger than me. Their bodies had swollen up as if they knew they wouldn’t live very long. All three of them, as if they had made a pact to inflate together.

Against every prediction, Estrella Azul made it to the finals against Toltecas. Patricio called to wish me luck. Then, casually, he added:

“The board of directors needs new recruits. They put a price on my contract.”

Every three or four years, Toltecas overhauls their roster. No other team makes as much in commissions. People like the triplets blow up. People like us get traded.

The first leg ended in a dirty 0-0. Patricio was kicked viciously. The referee turned out to be my parrot’s vet. He hated Argentinians. He didn’t call the fouls made on my friend. Even I gave Patricio a few extra kicks.

I don’t know what that second leg looked like from the outside. I never saw it on TV. For me, that afternoon marked the end of soccer, though movement remained an unending agony. We were 0-0 at minute 88. You could smell the disappointment of a final gone to penalties. Patricio had played like a ghost. We’d kicked him too much in the first match.

Suddenly, I swept the ball away and kept it. It was as if everything was spinning and the sun was beating down from inside me. There was a shattering silence, like when I woke half dead in the Nefertiti. I looked up, not at the field, but at the sky. Then I saw the grass all around me; an island, the very last island. It was like breaking open a fortune cookie. Everything stopped: the water in the electric waterfall, the sweat on the triplets’ cheeks, Nati’s hands on my back, the twelve teams who’d kicked me, the red, white and green jersey I never got to wear, the needle feeling for my nerves. And then I saw nothing, just the desert, the only place I could make a backwards play.

I heard a whistle. Patricio was open on the forward line. I saw his jersey, an enemy to both of us. I passed him the ball.

He was alone in front of the goalie, but simply scoring wasn’t enough for him. He launched a beautiful little curve shot that caressed the ball towards the corner. I admired this, the play I’d never been capable of making, which was now just as much mine as the jeers and insults and cups of beer they threw at me, and which finally meant something different.

I walked off the field and started my life.

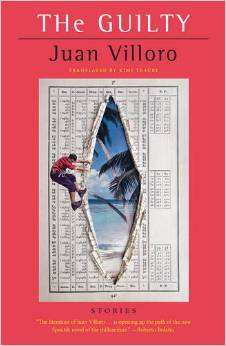

From THE GUILTY, translated by Kimi Traube. Used with the permission of George Braziller, Inc. Copyright © 2015 by Juan Villoro.