The Weight of Memory: On Motherhood and the Ghosts of Racial Violence

Cassandra Lane Considers Family History and the Nuances of Conception Stories

My history classes in small-town Louisiana schools, and later in a Louisiana college, were led by white teachers whose faces and names have long receded from my memory. They stood, symbols of authority, alongside blackboards against whose surfaces were scribbled small chalked numbers. These dates, chronicling ancient world and US events, slipped and skidded in my memory like shacks in a mudslide. The teachers droned on and on about the dates, their voices cardboard and smoke.

They were hiding something. I didn’t know it then. I internalized my thick confusion as a personal intellectual defect. I listened for the stories behind their dates. Something always rang hollow, but you do not know what to ask for when you do not know what is missing.

In study hall, the notes on my index cards mocked me. At test time, my memory failed me. Images of the cards and boards flashed in my mind—blank.

Recoiling from history in the same manner that I recoiled from calculus, my defense mechanism became, as I grew older, a proud declaration that I wore like a badge: I’m right-brained. I love words and art and nature, sensual and imaginative things.

I didn’t realize that history too—even when presented with a capital H—can be subjective, can be a work of the imagination. Or omission. When I was growing up, the old folks used to say, not telling the whole truth is a lie.

The word history hails from the Greek historia, which means knowing, learned, to see, to know. One definition states, “An account of what has or might have happened, especially in the form of a narrative, play, story or tale.”

Might have happened.

It can also mean “something that belongs to the past” or “someone or something regarded as no longer important, relevant, useful.”

To “make history” is to “be or do something important enough to be recorded.”

As a student, I didn’t learn the histories of my people or my people’s people. There must have been sections, or subsections, about Africa and slavery and Jim Crow and the civil rights movement. Right? But when I try to recall my education, which spanned the late 70s to the early 90s, it is a fog to which I cannot connect.

A universe of words swirled inside me, trapped.

Curiously, I chose to study journalism in undergraduate school, becoming the editor of my campus newspaper and then, fresh out of college, a newspaper reporter.

“How are you going to be a journalist?” my mother had asked worriedly when I first declared my major. “You don’t… talk to people.”

It was true: While she is all water and electricity and spoken words, I was timid and awkward and nervous. Petrified wood. Somewhat mum. A universe of words swirled inside me, trapped.

But the listening skills I had honed as a girl, eavesdropping on the conversations of my adult relatives and hanging around my grandparents and their friends, got me through as a young reporter. I learned what kinds of questions to ask. My eyes were big and unguarded, two pools reflecting what people read as compassion and interest. They spilled their responses into my ears. I carried reporter’s notebooks and pens and mini tape recorders as if they were missing limbs I had rescued. I pored over my chicken-scratch notes and transcribed recordings, piecing together my sources’ stories. The recorded interviews were always superior to my shorthand. When I used a recorder, I was not distracted by trying to write down my subjects’ words.

I could hone in on what they were saying, I could look them in their eyes. The recorded interviews captured their vocal tics, their sighs, their pauses, their tears and laughter, their “no, no—don’t put that part in.”

I was an antenna out in the world, tuning into stranger after stranger: astronauts and cancer survivors, city officials and celebrities. Somewhere along the way, I began to think, and then write, about my own family of origin.

How do we connect to all these floating lines of reportage and history and dates? In newspaper columns, I introduced some of the characters of my own life, especially holding reverence for my maternal grandparents, who had died by the mid-1990s.

Their voices had never been recorded, and this void haunts me still. They had been disenfranchised all their days on earth and now disembodied with no audio record of their embodiment. In my hours of greatest need, I strain to remember my grandparents’ cadences and vernacular, their singing and hums and deep-throated chants.

*

In 2017 I sat on the other side of the recording box. The New York Times had put out a call for essays about becoming a mother. I wrote a short essay about my conflicted relationship with motherhood and sent it in.

I wrote about how, at 16, I had decided, fervently, that I would not become a mother. Never, ever that.

I’d seen motherhood, black motherhood, up close: Mama working long hours and raising us children without our fathers’ assistance. My grandmother cooking and cleaning from sun up to sun down after we moved in with her and my grandfather; this when she was in her seventies and eighties and had long ago raised her eight children and should have been enjoying her freedom. And there was my great-grandmother, Mary, who had only had one child, my grandfather, but even that birth story was tragic. My great-grandfather, Burt Bridges, was lynched before Mary could deliver their baby for him to hold and to cherish.

No, motherhood would not dot my path. I would not bring another black child into a world of such oppression and lack. But I started having sex at 16 and got pregnant at 17, the age my mother was when she had me. I had an abortion as quickly as I could. My pledge not to give birth lasted for nearly 20 years, until something within me started shifting, and I yearned (predictably, perhaps) for a child.

At 36, after a determined ride in the other direction, my life changed drastically: I became a mother.

My story was selected as part of the New York Times’s series Conception: Six Stories of Becoming a Mother. To bring our stories to life in a new way, the producer, a visual journalist, would fly to each of our cities to have us retell our stories in sound studios. She would then edit those stories and hire animators to create moving animations to our recorded voices. The result would be a collection of animated videos that the paper would publish online.

The producer found a studio that was five minutes from my job at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles, where I was working at the time. We made plans to meet there one evening after work. I was nervous. I had agreed to speak aloud an intimate personal story—a story that even most of my family didn’t know—to an international audience. I worried, too, how lingering bronchitis symptoms, including a raspy voice and deep chest cough that sometimes felt as though it were strangling me, would impact the recording.

“Don’t worry about the cough,” the producer said. “We can edit that out.”

It was early May. Jacaranda trees flowered the Los Angeles streets with their falling purple blossoms. The studio was Echo Park cool. With 40,000 square feet of “sound sanctuary,” its interior was draped in a moody, retro style: jewel-colored walls, wall textiles, throw pillows, and rugs in earthy boho prints. My producer was a white woman, probably 10 or 15 years my junior. I handed her a bag of Dodgers hats and T-shirts, and she gushed. She introduced me to our sound engineer, who gave me a laid-back, friendly smile.

Why couldn’t I let the heaviness of my family’s past go?

A couple of guitars sat in stands on the floor, and I thought of my mother, a gospel guitarist. The producer motioned for me to sit behind a mic stand that was lowered in front of a wide, burnt-orange leather armchair. I sat down. The arms, gargantuan, were too high for me to rest on comfortably, but I tried to relax.

There was no warming up; the producer jumped right in.

“Let’s start from the beginning. Tell me about your childhood.”

I stuttered. The poetic river I’d been able to create in my essay was all of a sudden dried up; my words jumbled and meandered as I talked about my childhood, my mother’s divorce, our move back into her parents’ house, and how my great-grandmother was also living there.

Trying to tie it all to the motherhood connection, I brought up Grandma Mary’s lynching story.

“She was pregnant with my grandfather when the father of her child, my great-grandfather, was lynched in Mississippi in 1904,” I said.

The producer paused and raised one eyebrow slightly. Then she tilted her head.

“1904,” she said. “That was a long time ago.”

The year sounded so ancient coming from her mouth. It sounded like something that “belongs to the past… regarded as no longer important, relevant, useful.”

I felt silly, scolded, and silenced all at once. It was, again, 2017. I was 46 and raising a ten-year-old son in the middle of one of the most diverse cities in the world. I had left the South behind 16 years earlier. Why couldn’t I let the heaviness of my family’s past go?

Shame and anger whirled inside me, although I couldn’t quite put my finger on what piece of her response I had interpreted as injury, whether she meant it to be or not. Was it the subtle move of her head or brow, a shift in her tone, or the use of the phrase “a long time ago”?

As the interview continued, I sat there telling her the parts she wanted to hear, stopping to hack loudly when I could no longer suppress my coughs. I gulped water and wished that I had also swallowed the year of Burt’s lynching, that I had ended with “my great-grandfather was lynched.”

Period.

But 1904 is one of the historical years I know; it is seared into my cells and memory and writings about my family. As a fellow storyteller, I had wanted the producer to explore with me how the lynching story of my history—a man torn from his unborn child through one of the worst forms of racial violence this country has witnessed—might be a part of my psyche and my conception story.

It—1904—was a long time ago, yes. Still, those long-time-ago people were my grandparents and my great-grandparents, and for that alone, I love them. Burt was lynched nearly 70 years before my birth, but Mary survived, and I remember her. I remember bits and pieces of her. I remember the bitter and sweet of her. And since she lived until her nineties, Burt might have lived until his nineties too. His living might have spelled a better life for his son and his son’s children, for me and my child.

My lynching quote didn’t make it into the producer’s final cut. I understand. I was sharing a piece of my story, but she had the right to edit her final product as she saw fit.

Besides, I, too, was a revisionist. I told her my abortion story, how I married a man who was likewise staunchly opposed to having children, but I did not divulge how I destroyed that marriage with an affair. I said, instead, that we went our separate ways, implying that it was based on my changing views about parenthood.

When the story aired, I emailed my ex-husband.

“It’s just a slice of my larger story,” I wrote. “I will tell my whole story about what happened later.”

He said he understood.

My elders’ words sounded in my ears: not telling the whole truth is a lie.

__________________________________

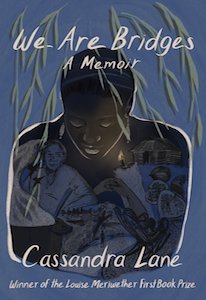

From We Are Bridges by Cassandra Lane. Published by the Feminist Press in April, 2021. Reproduced by permission.

Cassandra Lane

Cassandra Lane is a writer and editor based in Los Angeles. Lane received her MFA from Antioch University LA. Her stories have appeared in the New York Times’s Conception series, the Times-Picayune, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, and elsewhere. She is editor in chief of L.A. Parent magazine and formerly served on the board of the AROHO Foundation.