The View From Iran: On the Consequences of a Trump Presidency

Salar Abdoh Looks Ahead to the November Election

The graffiti looms several stories high from a building overlooking Karim Khan Bridge in downtown Tehran: Down with the USA; I pass it at least twice a day. For someone who divides his time between two cities, Tehran and New York, and who carries an American passport as well as an Iranian one, the cognitive dissonance is disturbing.

Lately, from my apartment in Tehran, I’ve experienced another sense of bewilderment as I’ve watched televised images of armed-to-the-teeth paramilitaries patrolling American streets, breaking heads and arms, pepper-spraying US citizens, and throwing tear gas grenades into their midst.

I ask myself: is this the America in which I live half my life, the purported beacon of democracy and free speech for the rest of the world?

Obviously, America means different things to different people. A continent-sized fantasy to the throngs who would give anything to reach its shores, to others it is the country that sends its drones and soldiers to faraway places to hunt and to kill. As an Iranian, and an American, most of my adult life has been a not-so-delicate reckoning with myself, because for all of my adult life Iran and America have been inveterate enemies.

The turmoil unfolding across American cities today in many ways resembles the daily reality of swaths of the Middle East ever since the start of the millennium, when the US brought boots on the ground to the region. Speaking recently with my friend Abu Masoumeh, a television news producer in Baghdad, he noted that in parts of the Iraqi capital and the Shia south, people ascribe what is happening nowadays—coronavirus, “civil war” in America, and economic blight in the Levant—to a curse; they note that these troubles started brewing after America’s assassination of Qassem Soleimani, Iran’s top general, and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, the deputy chief of Iraq’s Popular Mobilization force (Hashd al-Shaabi). While this line of thinking stretches the imagination (and certainly not every Iraqi or Shia feels this way), the essential point behind this fanciful notion reveals real anger and a sense of opportunities lost.

I ask myself: is this the America in which I live, the purported beacon of democracy and free speech for the rest of the world?

In the waning years of the Obama administration, as the battle against ISIS was reaching a fever pitch, I embedded with some of the Iraqi and Iranian volunteers fighting the Islamic State. It was also a time—the summer of 2015—when Iran and the US finally reached a landmark agreement designed to severely curb Iran’s nuclear ambitions, and in return bring the country out of the international isolation imposed upon it for so long by the United States. The deal was not perfect, but it was a start. And across the highways of Iraq, when the convoys of the Hashd al-Shaabi passed those of the Americans, or when we watched in awe at the sheer might of American airpower against ISIS targets—there was the sense that something was perhaps changing in the Middle East. We did not dare hope too much, but this tentative rapprochement between the US and Iran—and the fact that the Americans were, for all intents and purposes, fighting on the same side as us, in Iraq at least—portended that less hostile days might lie ahead.

During that time, as I shuttled back and forth between Iran, Iraq, and the US, where I hold a professorship, I interviewed the African American writer and my colleague Emily Raboteau for the Iranian journal Dastan, eager to better understand what was happening in cities across America. From halfway across the world, I could see that black American citizens were being killed at an alarming rate by their fellow citizens in law enforcement. (Raboteau had been documenting the Know Your Rights murals popping up all over New York as a way to address police brutality and impart information about what people can do when faced with harassment.) As New Yorkers, but specifically Harlemites, we also recalled that fateful day back in 2008 when Barack Obama clinched the Democratic nomination, and how the people of Harlem, including us, descended on the state office building on 125th Street to witness history unfolding.

By contrast, I was in the trenches in Iraq when news of Donald Trump’s win came to us in November 2016. At the time, a lot of regular Iraqis and Iranians thought this was of little consequence. Even my friend Abu Masoumeh told me, “It makes no difference. The Americans, they are all the same.”

But Americans are not all the same. Just as Iranians or Iraqis are not all the same—after all, there were vigils held in the streets of Tehran in tribute to George Floyd. But as Mr. Trump destroyed the nuclear deal and then doubled down on the suffocating economic sanctions on Iran, black American citizens kept getting killed in the streets. Then, rather than bringing a modicum of peace to its burning cities, the American president chose tear gas and batons. It is hard to imagine that a different American president, more savvy and more in tune with the plight of people in his own country and around the world, would have chosen such destructive paths.

I am struck by how things might have been different for both nations. Of course, it is naïve to think that America’s trauma will suddenly come to an end if there is a change in the White House come November. Nor should we expect the bad blood between the US and Iran to cease completely and immediately with a different American president.

But imagining a different path forward is not impossible, rather than ongoing disaster we now face. Iranians held vigils for George Floyd, like so many other people around the world, not because they were forced to do it; they did it because, aside from it being an act of humanity and empathy, in George Floyd they saw a bit of themselves—as individuals and collectively, as a nation, being smothered under the weight of injustice aimed at them by a superpower. This is why Iran, alongside America, awaits November.

__________________________________

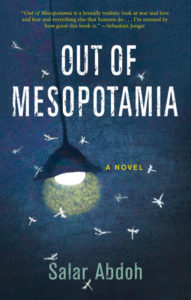

Out of Mesopotamia by Salar Abdoh is available now from Akashic Books.

Salar Abdoh

Salar Abdoh was born in Iran and splits his time between Tehran and New York City. He is the author of the novels Tehran at Twilight, The Poet Game, Opium, and Out of Mesopotamia and the editor of Tehran Noir. He teaches in the MFA program at the City College of New York.