The Unexpected Pleasures of Being a Late Bloomer, in Motherhood and Writing

E.J. Levy on Writing Through Literary Vanity

In my last months of high school, my best friend—who should have been my girlfriend—was the yearbook editor, a role that conferred on her the right to caption photos. She wrote of mine, “Ellen Levy, the girl who could do anything well, late but well.” I resented the comment—astute, admiring, and hostile, like high-school friendship itself, that minefield of ambivalence. Decades later, a beautiful glamorous Broadway dancer with whom I was in love told me, “Never give a person a gift in the middle of their personality. They’ll feel summed up.” The yearbook caption had been that for me: I’d felt seen and dismissed simultaneously, summed up.

Now, as a soon-to-be debut novelist past the age of 50 with a child in first grade and hands that suddenly look like my aged mother’s—protuberant veins and crepe-y skin, freckles unnervingly like age spots, which they likely are—that old high-school yearbook prophecy appears to have come true at long last: late but well. Late but true.

I used to track the ages of artists I admired, checking to see how old each was when she or he published a given work (first book, best book), comparing myself anxiously to them; I was reassured when they launched late. Virginia Woolf and many other women were a decade older than their male peers when they published first books, according to my anxious measurements: Christopher Isherwood (24); James Baldwin (29); Virginia Woolf (first, 33; best, 49), Audre Lorde (34), Maxine Hong Kingston (35), Vivian Gornick (first, 38; best 51), Toni Morrison (first 39, best 46), Annie Proulx (56), Louis Begley (57), Daniel Dafoe (59), Frank McCourt (60), Penelope Fitzgerald (61).

But there’s no denying it—I’m late to this party, to parenting and publishing both, and though I may possibly still look somewhat younger than my age, it’s catching up to me fast, now that I’ve hit menopause. My memory’s suddenly shot, my skin loose, my belly now round and soft. I no longer look “coltish,” as ex-girlfriends used to call me. I look like what I am—that social pariah—a middle-aged white mom, even as I resist such reductive summing up of myself or others, our current penchant for categorizing and dismissing one another (the categorical that art worthy of the name defies).

*

When I first took up writing in my thirties—enrolling in an evening extension class at City College, then in an MFA Program in the Midwest, from which I dropped out after a bad breakup with a girlfriend—I confided to a writer friend that I aspired to be a minor Philip Roth; she laughed. “If you plan to fall short, don’t you think you should aim higher?” Now, reading a review of Roth’s since pulled authorized biography, I learn that when Roth was in his fifties (as I am in mine), he’d already published 15 books and he had a heart attack, followed by a quintuple bypass. David Remnick describes the period that followed Roth’s surgery as “one of the great late-career outbursts of creativity in the history of American literature” (italics mine). I cringe. Late-career? I’m starting where he began to flag, if I’m even in the race.

*

People often ask my age, and I refuse to answer, not from female vanity but from literary vanity. I’m simply too young a writer to be this old. Should be further along. It’s hard to explain that I received my MFA at 40: at the time, I was wooed by many agents; I had a novel draft whose first hundred pages a renowned literary editor loved and asked to read the rest of; my work was chosen for Best American Essays; I seemed poised, finally, to be the writer I’d hoped and meant and worked for years to be. Then, abruptly, my father died and I put the novel away, left my tenure-track job, walked out on my life, walked out on myself, walked out on the pain that seemed impossible to weather.

People often ask my age, and I refuse to answer, not from female vanity but from literary vanity. I’m simply too young a writer to be this old.I was derailed, devastated by my father’s unexpected death—more than an overdue end of childhood, I felt exposed by his death, unsheltered, and all the comforts of connection I’d formerly disdained I suddenly urgently wanted. I would spend a decade finding them and building a home in the world, safe harbor, even as I know (and knew then) that we are never safe; we can only be courageous.

One of the more courageous things I’ve done mid-life was to date outside my genre: a lesbian, I married a lovely man after I became unexpectedly pregnant at the age of 47. My greatest fear was not that geriatric pregnancy might be perilous or downright dangerous (although it is, with maternal death more than 100 times likelier after age 45), but that I would find myself, as I’d always believed, temperamentally unsuited to maternity, to parenthood, and especially to motherhood, to the sustained nurturing and devotion that women are expected to possess, but which I never had. Though I would miscarry a few months later, I would get pregnant again and give birth uneventfully.

I was shocked to find that I enjoyed motherhood, even as I was exhausted, stunned, even as parenthood proved to be an intellectual catastrophe. My decades-long practice of reading and writing was upended; gone was the structured discipline that had seen me through adulthood thus far, gradually deepening the course of my life and my thoughts. In my late twenties and thirties, I had consciously built a brain and a life—from music, film, books, a careful construction of attention, or rather a curation of consciousness, finding my place in things by finding what I loved. Such disciplined attention to art and literature and music did not feel acquisitive; it was more like echolocation or charting by stars.

My partner and I have been surprisingly happy together. But over the seven years since our child’s birth, and especially since the pandemic shutdown last March, I have begun to fear that I’ve “socially distanced myself from myself” (as essayist Maureen Stanton aptly put it) by marrying and becoming a parent. I am disoriented by relentless company, by that heterosexual masculine complaisance that I’d simply dismissed and ignored after I came out as a lesbian at 25.

But increasingly I wonder if it’s not het marriage that’s undone me, but age.

As I write this, I am sitting in my small parked car in a driveway in a small town in the American West during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, under stay-at-home orders, trying to find a little solitude in our relentless confinement. I’m grateful for this shelter in this storm, for our relative safety, even as I know that what is needed maybe is not safety but courage to stand up for what is right, for justice especially for the most vulnerable (which my ancestors were a century ago), and to sit down and write. To take notes on this strange and marvelous and fragile time we live in, when it seems the beautiful world itself may have an expiration date.

*

At her fortieth-birthday party, a poet friend said, “You spend the first half of your life gathering things to you, and the second half letting them go.” I disagree: past 50, I’m still gathering.

At her fortieth-birthday party, a poet friend said, “You spend the first half of your life gathering things to you, and the second half letting them go.” I disagree: past 50, I’m still gathering.So what is one to do when one comes to the beloved late, knowing loss is inevitable and may come at any time (a grim fact the pandemic lets few forget)? I was cavalier when young about love and relationships, discarding them readily, as if commitment and connection were encumbrance; now I cling, knowing it will run through my hands, all I love, like sand, like time itself.

*

On days that he arrived at the writing desk after 9 am, Roth thought, “Malamud has already been at it for two hours.” When I get to the desk now, I think, Roth had been at it for 30 years already. When my debut novel sold two years ago, I bought myself a present out of the advance: Roth’s reading chair, in which he sits for the famous TIME photo, circa 1969.

My daughter asks me how old I am; I tell her, “In my fifties.” She’s not buying it. ‘But what age in your fifties?” I do not want to answer, not from literary vanity or female vanity but from fear that it will scare her, my age, as it scares me. When I first got pregnant, accidentally, in my late forties, I thought I was on another time clock from others, my family more like lobsters that grow more fertile as they age. But time comes for all of us, and I feel now that it’s coming for me at last. I do not want my daughter to feel the precarity of us, our robust days. How easily they might break on the rocks of days.

There is nothing to be done about the passage of time, of course. There is nothing to do but stand up for what is right and sit down at the desk, while I still have time, and write.

____________________________________________________

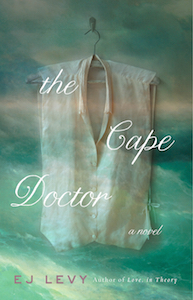

E.J. Levy’s The Cape Doctor is available now via Little, Brown.