The Uncertain Future of Sweden's Floating Libraries

On the Boats Bringing Books to Thousands Who Need Them

On a cold morning in a port a few miles outside Stockholm, a group of boys who don’t usually read are huddled around a table of books.

“Is there any more coffee?” one of them shouts.

The boys live on the Swedish island of Möja, a quiet, green island dotted with villages that house around 200 full-time residents and one library. The library they’re currently in, however, has hundreds more books than they normally see in one place, and it comes to them on the water.

The Stockholm county library boat (or bokbåten), visits 23 islands, including Möja, in the Stockholm archipelago, for one week twice a year. It carries around 3,000 books and a rotating staff of three to four librarians.

When it docks, island residents have about one-and-a-half glorious hours to come aboard the motor ship, browse its treasures, and borrow anything they’d like. Each island has one library card and, in a delightful detail, there are no penalties if a book isn’t returned six months later.

The bokbåten is a manifestation of a strong literary tradition across Scandinavia, where literacy rates are among the highest in the world, and both boat and bus libraries bring books to rural or otherwise underserved communities.

Funded by the Regional Library in Stockholm with contributions from four municipalities that it serves, the Swedish bokbåten routinely buys new books. There is strong demand for the newest bestsellers and also the pesky fact that some books just are never returned. (Some do, however, turn up years later.) The rest of the funding goes to pay for operational costs, like renting the boat (currently a motor ship called Rödlöga) and lodging the volunteer librarians.

It’s early in the morning on Möja, but the boat is filled with bustling yellow-haired children and adults bundled up in jumpsuits and boots against the cold sea air.

“I got 7 books!” 11-year old Chester Undin says. When I ask what his favorite books are, he replies, “scary books and [ones about] doggies.” He will leave the boat with a stack of books, including a hardcover simply entitled “Parkour!”

Christina Hallingström (L) and Maria Anderhagen (R) are among a group of librarians who work on the bokbåten when it sails around the Stockholm archipelago twice a year. Photo by Anjie Zheng

Christina Hallingström (L) and Maria Anderhagen (R) are among a group of librarians who work on the bokbåten when it sails around the Stockholm archipelago twice a year. Photo by Anjie Zheng

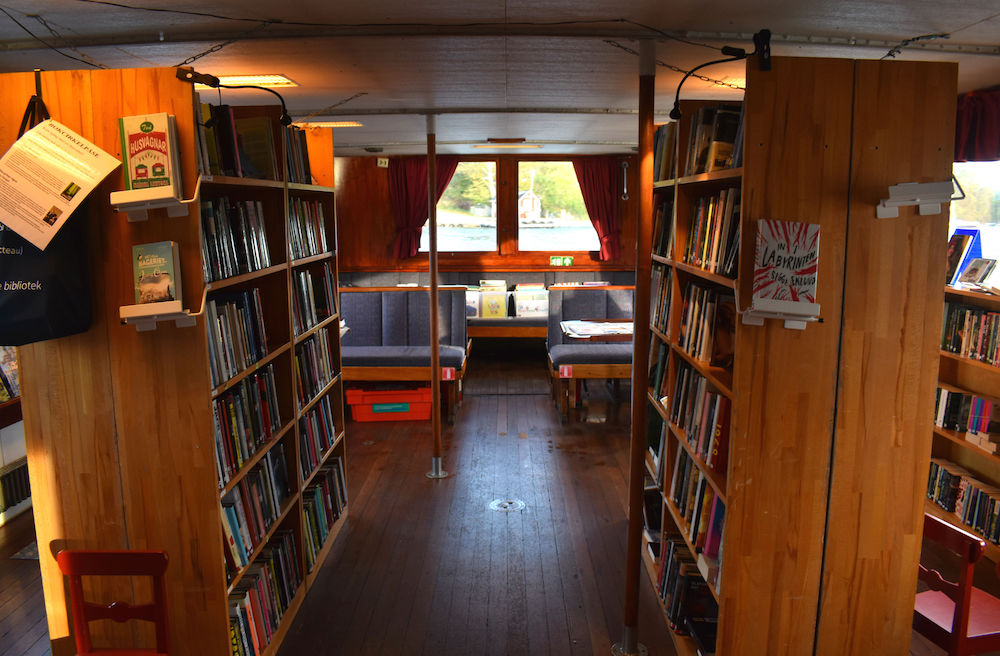

First started in 1953, the bokbåten beats out Norway’s Epos boat (established in 1959) as the oldest library boat in Scandinavia by a nose. This latest motor ship that carries the bokbåten brings to mind the libraries of my childhood. There are tall wooden shelves, large tables displaying sturdy hardcovers, book carts on wheels, a long checkout table, even event notices taped against the wall (“Meet local children’s authors, 29 October, at 10 am!”).

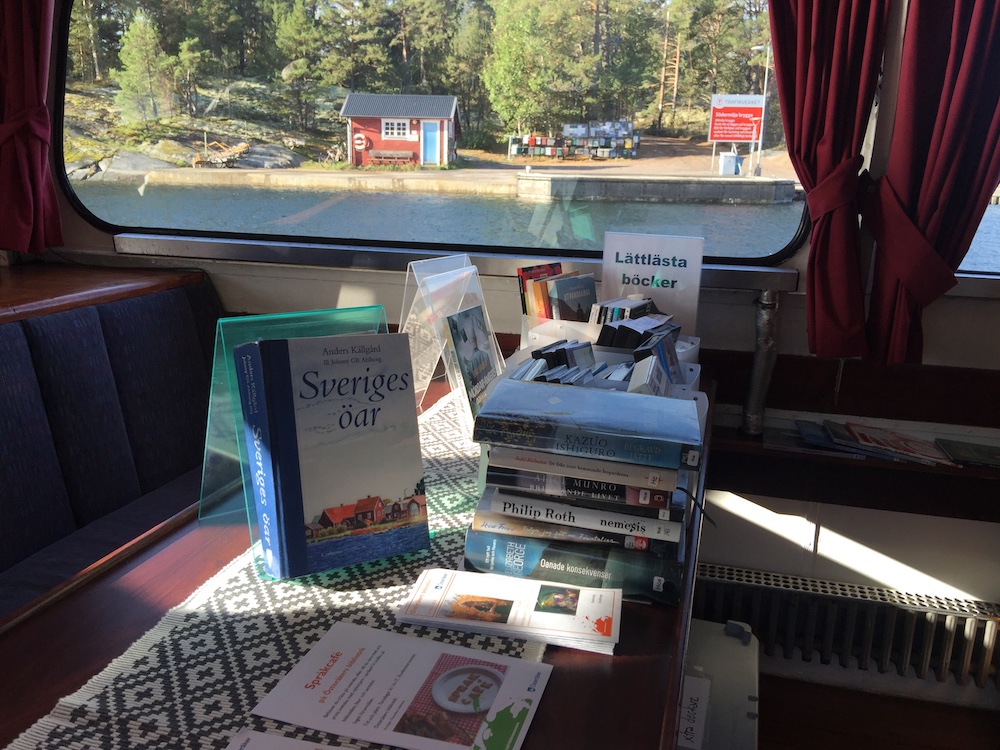

There are picture books for children, popular thrillers, large-print books, texts about history and science and knitting, cookbooks, and audiobooks. Since island residents can order copies in advance, boxes of books are stacked around the boat waiting to be delivered.

I’m in awe as I examine a pile of books on a nearby table that includes Swedish translations of Philip Roth, Kazuo Ishiguro, and Alice Munro. When a woman with short cropped salt-and-pepper hair catches me ogling, she stops her browsing and says, “Those are mine.”

“It’s not old scruffy books we have,” says Maria Anderhagen, the coordinator of the bokbåten. Many of their books sport stiff spines and thick pages, and are devoid of stamped cards in back pockets.

Photo by Anjie Zheng

Photo by Anjie Zheng

Anderhagen, a warm woman in a red, butterfly-print dress, took over managing operations for the book boat from in early 2018. The Regional Library, which previously managed the boat, handed over responsibilities to Anderhagen in large part because her home library in the municipality of Norrtälje had the largest basement. When not sailing the other 50 weeks of the year, the thousands of books are unloaded from the bokbåten and stored in a library basement.

“All the other libraries are downscaling and they didn’t have extra space,” she says. “What I’d really like is for all the books to go, so I don’t have to bring them back!”

The other two librarians on the boat, Christina and Brittmari, are busy unloading boxes of books brought back from the Möja library and checking out books the residents are taking this time.

A troop of four children with dark eyes and hair, all under the age of seven, board the boat. They’re the children of a Syrian refugee who fled the civil war there a few years ago, Eva Ejemyr, 70, tells me. Ejemyr befriended him through her work in non-profits in Stockholm and invited him and his family to live as tenants on her property on Möja, as rents are much lower there than in the city.

“The children have just been here 10 months, and they’ve already learned Swedish!” Ejemyr says. She hands out black plastic bags to each of the children and they quickly fill them up with books.

A frequenter of the bokbåten for 24 years, Ejemyr tells me she also ordered books in Arabic for the children’s parents. That way, she says, the children can read in Swedish, and the parents can read in Arabic. The books will be delivered to the library on the island in 2 weeks.

*

Boat libraries in Scandinavia were borne as much out of necessity as a cultural reverence for reading.

There are over 24,000 islands in the Stockholm archipelago, most of which are uninhabitable rocks. Some, like Möja, have a few hundred full-time residents. The most picturesque of the islands are populated with vacation homes and are packed in the summer months. Children who grow up on the islands attend school there, but many of their parents commute to the mainland of Stockholm city for work. Routine errands, such as a visit to the dentist, are usually also done on the mainland, and this can easily result in a full day of travel by boat.

When the bokbåten embarked on its maiden voyage in 1953, it became the primary way the thousands of residents living on the islands in the Stockholm archipelago could get new books.

That tradition is still there, if in a less pressing sense. According to the updated Swedish Library Act of 2014, each municipality is mandated to have at least one library. Yet the quality of those libraries vary greatly. Although some islands have a small library, they tend to have fewer resources. The modern library boat brings newer books, and more of them, to the islands. It also brings another invaluable resource many islands don’t have: librarians.

When the bokbåten embarked on its maiden voyage in 1953, it became the primary way the thousands of residents living on the islands in the Stockholm archipelago could get new books.

“They’re very helpful in helping me find books,” says Ann Pantesjö, 63, a teacher on Möja. The books about the history of the archipelago she borrows will be extra useful, she says, since the curriculum for the next school year includes the 18th century Russian invasion of the Stockholm archipelago.

“The Scandinavian countries have a long history of [the] welfare state where literacy and learning are considered important,” says Päivi Jokitalo, a Finnish library specialist. “The library systems stress equal access to literature and knowledge for all, regardless of background.”

The interior of a Swedish floating library. Photo by Anjie Zheng

The interior of a Swedish floating library. Photo by Anjie Zheng

Yet even with strong literary traditions, some local authorities in Scandinavia have decided to eliminate services that they think are no longer worth it. While the Finnish government has spent nearly 100 million euros on a splashy new central library in Helsinki, the regional government cut funding to a Finnish library boat that was in service for over 30 years. It was costly to maintain a library boat in the few summer months when the water isn’t frozen over, and the communities served tend to be sparse, says Jokitalo of the Finnish boat library.

While Sweden’s bokbåten is still operating, Anderhagen acknowledges that its future is far from certain.

“If the Regional Library feels we can’t afford to spend this money, then we won’t be able to have this boat anymore,” she says.

The bokbåten may be a holdover from the past, perhaps even something uneconomical. But the metrics of commerce were never apt for a place where no money is exchanged. The excitement of browsing for new treasures and leaving with new reading you did not have to pay for—the joy of everyone onboard the bokbåten—was undeniable. The mere existence of the boat library elevates the thrill of a quotidian library visit to be a highly anticipated biannual event.

“The library on Möja is just opened once a week. I never visit the school library to borrow books,” says Lucas Rubin, 15. His friends, also sitting around a table with coffee and snacks, echo this point.

While Sweden’s bokbåten is still operating, its future is far from certain.

Jimmy Kjellgren, also 15, nods. “I like that you don’t have to go to the mainland to get a book,” he says.

Their joy is earnest, the declarations made without any of their teachers in earshot. Near the teenage boys, rosy-cheeked 4-year-olds pull up tiny chairs under sunny windows to sit quietly and flip through colorful picture books.

Photo by Anjie Zheng

Photo by Anjie Zheng

The Regional Library in Stockholm, which funds the bokbåten, categorizes the bokbåten in its annual plan under a section called “Democracy,” saying “Everyone should have access to library services.”

“It’s an issue of democracy for everyone to have access to books,” Anderhagen says. “Even if you live out here you should have access to knowledge and facts and librarians to help you find that. It should be equal wherever you live in our country.”

As she leaves the boat, I catch Ejemyr with bags full of books, including a cookbook titled “Kimchi and Kombucha.” To help with her digestion, she explains.

“I look forward to this every year,” Ejemyr says of the bokbåten. “We all do!”

Anjie Zheng

Anjie Zheng is a writer based in Brooklyn. A former reporter for The Wall Street Journal, her writing has also appeared in Quartz, LA Review of Books China Channel, and Words Without Borders.