The Troubled Task of Defining Southern Literature in 2021

Ed Tarkington Reckons with a Fraught Literary History

In 2016, while touring in support of my debut novel, Only Love Can Break Your Heart, I appeared on a panel at the Mississippi Book Festival in Jackson. Despite (or perhaps because of) its troubled history, Mississippi is the Ground Zero of Southern literature, chiefly because of the towering omnipresence of Faulkner. But there’s also Eudora Welty, and Richard Wright, and Walker Percy, and a host of their peers and heirs—Shelby Foote, Willie Morris, Barry Hannah, Lewis Nordan, Richard Ford, Donna Tartt, Jesmyn Ward, Kiese Laymon—the list goes on and on.

Add to it the name of another writer appearing beside me on that festival panel: the late, great Brad Watson, who passed away suddenly in early July—one of several devastating losses for literature and publishing in a generally devastating year, and the one I took most personally. In my mid-twenties, I had discovered Brad’s debut story collection, Last Days of the Dog Men, a book which redefined for me what was possible for a bookish Southern white boy uncomfortable with the idea of “Southernness.”

Not long after, when I was in graduate school at the Florida State University Creative Writing Program, Brad visited to read from his novel The Heaven of Mercury, which had recently been named a finalist for the National Book Award, and which I’d already read twice. I arranged to interview him for the Southeast Review, where I was then the fiction editor. It’s scary sometimes to meet your heroes; they might not like you, and you might not like them. This was not the case with Brad Watson. If he didn’t like me, he was too sweet and gentle a soul to show it. He was also impossibly cool. He wore boots and jeans and aviator sunglasses and a beard long before beards became trendy. He spoke slowly in a low lilting baritone drawl, slouching in his chair while amiably answering my too-long questions between puffs on a hand-rolled cigarette. He managed somehow at once to come across as deeply humble and completely sure of himself in a way I had never felt nor have yet to feel.

Brad’s reading that night was held in the back room of a dingy pool hall and concert venue called The Warehouse, a Tallahassee institution that has since been bulldozed. The packed, stiflingly hot room listened in rapt silence as Brad read a strangely luminous passage from Mercury set in the basement of a funeral parlor involving sexual initiation via necrophilia followed by an apparently miraculous resurrection. His capacity to endow something uncanny and improbable and even sordid with tenderness and beauty: This may very well be the best way to explain the unique genius of Brad Watson.

To be on a panel many years later with Brad in his home state of Mississippi, the Mecca of Southern writing, made me feel like a kid in a garage band being invited to come onstage with Elvis, even though I was well aware that the arrangement was largely circumstantial; we both had books out that year. The panel was moderated by M.O. (Neal) Walsh, and also featured Lee Clay Johnson, Steve Yates, and Paulette Boudreaux. Presumably because all of our books were set in Southern states—Brad’s and Paulette’s in Mississippi, Neal’s in Louisiana, Steve’s in Missouri, mine and Lee’s in Virginia—the festival organizers had titled our panel “Southern Fiction Today.”

The young man—himself white—spoke of “patriarchal structures” and “white supremacist paradigms.” The mood of the room grew shifty and irritable.

It says a lot about me, and perhaps about the state of the South as late as 2016, that I didn’t give any thought to the fact that, of the six writers on the “Southern Fiction Today” panel at the Mississippi Book Festival, only one was a woman, and only one was African-American, and they were the same person, the gifted and exceedingly gracious Paulette Boudreaux. I didn’t think about this at all, in fact, until, near the end of the hour, a young man sitting near the rear of the crowded hall stood and rather bluntly asked what the fact that a panel on Southern fiction consisted of five white men and one Black woman said about how we conceptualize Southern literature.

The young man—himself white—spoke of “patriarchal structures” and “white supremacist paradigms.” The mood of the room grew shifty and irritable. A few of us offered varyingly clumsy replies. Neal Walsh amiably observed that as writers, we don’t think at all about “patriarchal structures;” we’re just trying to “make sure this paragraph doesn’t suck.”

Later that evening, most of the panel reconvened at the author party: a special off-site broadcast of Oxford’s Thacker Mountain Radio Hour, hosted by Mississippi writer and raconteur Jim Dees, and featuring a conversation with another beloved Southern writer lost in 2020, Julia Reed. The festival had paid all of our honoraria with crisp $50 bills; more than one person remarked on the comically absurd image of dozens of writers—a notoriously cash-poor and thirsty lot—leaning across the bar waving fifties at the beleaguered bartender.

I’d always assumed I was on the right side of such arguments, rather than representative of “patriarchal structures” and “white supremacist paradigms.”

The “Southern Literature Today” panel debrief revolved largely around our indignation at the comments from the man we all concluded was most likely a graduate student, with his “structures” and “-isms.” How dare he cast aspersions on our panel’s lack of diversity? We were just storytellers, after all. And we hadn’t organized the panel, we’d just accepted the invitation! Nor had we appointed ourselves spokespersons for “Southern Literature Today”—in fact, much our conversation had revolved around the fuzziness of the whole idea: how it seemed more of a branding concept, perhaps useful as an organizing principle, but perhaps also unfairly limiting. A more honest name for the panel would have been “M.O. Walsh in Conversation with Brad Watson and Some Other People You’ve Probably Never Heard of Who Published Books This Year.” Certainly, no one had expected the audience to interpret the demographics of the panel as a political statement.

At the time, I felt less indignant than embarrassed—even ashamed. All my adult life, I’d just wanted to be a real writer like Brad Watson; to have a book in print, to be invited places to talk about it, and about other books that I loved, and about what writing means or ought to mean. I’d always assumed I was on the right side of such arguments, rather than representative of “patriarchal structures” and “white supremacist paradigms.”

I looked at Brad. He was typically sanguine.

Brad Watson always seemed younger to me than his years. He was handsome, possessed of a rustic charisma reminiscent of Sam Shepard. Indeed, Brad had gone to Hollywood as a young man. And he’d been living for several years in Wyoming, on a horse ranch, where his wife, Nell Hanley (a gifted writer in her own right), had started a hoof-care business, which meant Brad could fairly be called a cowboy. He liked to laugh, and he moved with a springy lightness that made him seem perpetually boyish, despite the gray in his beard. But he was older, and wiser, and he was a great teacher.

He looked back at me.

“Say Ed,” he asked. “You still got that old dog of yours?”

I shook my head.

“No,” I said. “We had to put him down.”

“I’m sorry to hear it,” he said. “He was a good dog.”

“He sure was.”

He glanced off into the distance.

“It’s always hard, you know,” he said. “Putting down a dog.”

*

At the time, I thought Brad was just changing the subject. “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent,” Wittgenstein said, and there didn’t seem to be much else worth saying about “Southern Fiction Today,” at least at the time. Looking back, however, I see a metaphor.

The deconstruction and demolition of so many of the myths about Southern culture and identity has been ongoing in literature for a long time but seems to have accelerated at a stunning rate in the past four years, and especially at the start of this year. The combined effects of these historic circumstances are extra-literary, but they have nevertheless set off an appropriate reexamination of what truth means for fiction in the past, present, and future.

Perhaps the most troubling epiphany for white Southerners, literary and otherwise, has been the widespread acknowledgment of the continuing pervasiveness of white supremacy. This is a hard truth to swallow for people who have grown up unconscious of the extent to which they have historically benefited and continue to benefit from a status quo foundationally rooted in a moral evil, one which still infects so many through their inherited biases. Donald Trump’s craven, heedless bigotry has forced a confrontation with the racism which so many of us had falsely reassured ourselves to be a thing of the past.

Another hero of mine, and another member of that Mississippi “Murderer’s Row” of celebrated writers, is Walker Percy. In 1962, Percy appeared on the Today show after his debut novel The Moviegoer was the surprise winner of the National Book Award. When the host somewhat snidely asked him why the South produces so much great literature, Dr. Percy tersely replied, “Because we lost the war.”

By all accounts, this was simply a reflexive clap-back, and somewhat ironic, given Percy’s insistence that The Moviegoer was essentially a European novel of ideas set in the contemporary American South. A few weeks later, Percy received a letter of congratulations from Flannery O’Connor, with whom Percy shared a sharp wit and a low threshold of tolerance for condescension. “I’m glad we lost the war and you won the National Book Award,” O’Connor wrote.

What neither Percy nor O’Connor may have understood then as they might today was that the real war never ended. And the stakes are much higher than a beef over regional pride.

Recently, Claudia Rankine told The New York Times, “I wish writers would consider more deeply how whiteness is constructed in their work. The unmarked ways in which our white supremacist orientations get replicated in books and go unquestioned in theory remain one of the most insidious ways racist ideas continue to shape our consciousness.”

This is the recognition and the grief of “Southern Fiction Today”: how inextricable Percy’s and O’Connor’s whiteness are from their work; how impossible it was—and is—for white writers to “tell about the South” without fighting that same old war.

*

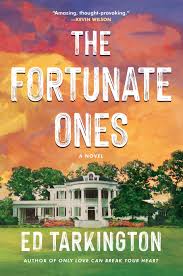

I have thought often in the past few years about how it felt to be called out for the white-maleness of that panel. I took the question deeply to heart as I wrote my next novel, The Fortunate Ones.

I wanted to write about how every aspect of our lives today is still conditioned by battles that started centuries ago, preceding that war the South supposedly lost but which never really ended. I wanted to write about the love-hate relationship between the have-nots and the haves and the often-destructive allure of wealth and the perils of noblesse oblige. I wanted to write a book that shows how entitlement gets internalized, and about why those who come from the bottom—“the deplorables;” the type of people to whom Trump purportedly refers in private as “losers”—would worship him, even to the extent of being willing to destroy the country they elected him to govern.

I want to lose the war—again, and again, and again, until it’s really, finally over.

Near the midpoint of The Fortunate Ones, one of the characters cites a Latin aphorism from El Brocense, a 16th-century Spanish priest who faced the Inquisition for daring to criticize the Gospels as literature: “Latet enim veritas, sed nihil pretiosius veritate.” Truth is hidden, but nothing is more beautiful than the truth.

*

When I got the word that Brad had died, the news left me dazed and weak. My face must have showed it; my 13-year-old daughter stopped in her tracks when she saw me.

“What’s wrong, Daddy?” she asked.

“Someone I know died,” I said.

“Who?”

“Someone very special to me,” I said.

For the remainder of the day, I teetered on the edge of weeping openly in front of my wife and our young children. I tried to numb the grief in the predictable manner—predictably, to no avail. That night, my dreams were strange and vivid. This was when I remembered (or perhaps imagined) what Brad had said to me about “putting down the dog.”

Brad never cared much for the “Southern writer” label, nor for the matter of what defines “Southern Fiction Today,” though he was always gracious and did his level best to answer questions on the subject thoughtfully without seeming annoyed. Brad’s writing wasn’t preoccupied with Southern culture or identity; he was interested in humanity, and language, and mystery. I have thought a lot about what Brad would make of the events of the past few weeks. I don’t have to wonder how he felt about Trump, but I’d like to ask him what can be done to save the South from itself.

When I think of Brad and the Southern-ness of his writing, I think less about setting than about the music of Southern language: the slow cadence, the lyricism, the juxtaposition of genteel, elevated diction, and the alliterative rhythm of the rural voice that is both homespun and Homeric. But I also think about the way he wrestled with the burden of being a Southerner, and the challenge of wrestling with the South’s contradictions, and the struggle to make peace with them—to hate the sin and still love the sinner; to know when it’s time to put down the dog.

As the South goes, so goes the nation. Today, I think, stories set in the South should be recognized not as stories about a particular place and time, but as microcosms of the great crucible in which all Americans now labor in our ongoing struggle over the future of our country’s divided soul. “I don’t hate it! I don’t hate it!” says Faulkner’s Quentin Compson at the end of Absalom, Absalom! I’m with Quentin; I don’t hate it. But I want to be honest about it, and about and with myself. I want to lose the war—again, and again, and again, until it’s really, finally over.

__________________________________

The Fortunate Ones by Ed Tarkington is available via Algonquin Books.

Ed Tarkington

Ed Tarkington’s debut novel Only Love Can Break Your Heart was an ABA Indies Introduce selection, an Indie Next pick, a Book of the Month Club Main Selection, and a Southern Independent Booksellers Association bestseller. A regular contributor to Chapter16.org, his articles, essays, and stories have appeared in a variety of publications including the Nashville Scene, Memphis Commercial Appeal, Knoxville News-Sentinel, and Lit Hub. He lives in Nashville, Tennessee.