The Tragedies of Aeschylus Are Truly Timeless

Ismail Kadare on the Greatest of the Greeks

There is a striking moment, unparalleled in its grotesquery and courage, in Aristophanes’s comedy, The Frogs: two groups of dead people engage in a debate regarding the art of the two great tragedians, Aeschylus and Euripides. In order to arbitrate the dispute between the two clans, the judges are obliged to weigh in on the balance of stanzas, imagery, and metaphors between the two rivals. This moment constitutes the first analysis of Aeschylian art. Meaningful in its own right and made not long after the death of the tragedians, this dispute was as prophetic for the victor, Aeschylus, as it was for the loser.

Unwittingly, Aristophanes revealed a fundamental feature of Aeschylus: the tragedian’s majestic constructions are made of deep foundations with details of particular value. The weighing of these details—the verses, imagery, and metaphors—allows us to realize that the entire edifice of Aeschylus’s literary work, consisting of smaller units, should be considered as treasures.

If we imagine that the core gravitational pull of the mechanism that sets Aeschylus’s drama in motion breaks, then the parts of the mechanism that dislodge from the whole still retain their independent value, much like the precious stones of a broken watch. In short, the isolated, raw materials used by the tragedian are resplendent, and when they are integrated into drama their worth only multiplies.

As the offspring of a happy marriage between poetry and drama, Greek tragedy remains beautiful even when its dramatic mechanism does not work perfectly.

In the famous infernal controversy imagined by Aristophanes, Aeschylus is blamed by his adversaries for a cold, frightful, and ominous brilliance. In truth, despite its monumentality, his work is filled with fragile, rainbow-like orchestrations like few others. It is hard to find another playwright with such a wide arc of colors, ranging from the stately black, to the sweeter, brighter tones. The resonance varies surprisingly from place to place within a work, or even within a single scene. Among the black clouds, amid the squabble of deities, macabre feasts, and the axes of crime, one finds the wonderful tranquility of human happiness, the approach of old age, and, of course, the sadness of a man abandoned by his wife.

But alongside these glass verses, in watercolor, one can be suddenly plagued by dark premonitions, murder, and the chorus howling over the cut-up body of the king.

Aeschylus’s creation of metaphors is most unexpected and diverse. In order to give Orestes a spiritual blow if he does not avenge his father’s blood, the tragedian works with cosmic dimensions, envisioning a time of remorse like a stretch of complete hopelessness. Meanwhile, he creates figures from the tangible, surrounding world—such as livestock, trees, road dust, horse bridles, vessels, and fishermen—with the same ease.

Aeschylus cannot be accommodated by any clichés. Not only the characters, but also their climate and interdependencies are unexpected, gyrating like different stages of a storm. Suffice it to recall here the last part of Agamemnon, when Clytemnestra, after spewing venom and hatred against her killed husband, after decrying his murder of their daughter, and after giving orders to bury him without honor, suddenly says:

I struck him and killed him, I’ll bury him too,

But not with mourners from home in his train,

No, Iphigeneia, his daughter shall come,

As is meet, to receive him, her father, beside

Those waters of wailing, and throwing her arms

On his neck with a kiss she shall greet him.

The reader is, and rightfully so, surprised at these words. Why would a woman, still trembling from rage against the dead, who, as the chorus says, considers the droplets of blood on her forehead ornamental jewels, declare something so empathetic? Her statement evokes Agamemnon’s deep loneliness and the sadness he might feel when the only person to come forward to embrace him is the daughter he sacrificed. Another question arises: why would the girl do this? What would motivate her to greet her killer with open arms?

The questions continue on, and through these inquiries we realize that the tragedian has said something, in passing and mysteriously, that is much larger than our contemptible questions. He has spoken a truth about the reconciliation of the father and his daughter, who both have been wounded at the Trojan campaign, one at the beginning, and the other at the end.

When you step into the world of ancient literature, you realize the naïveté of theses that speak of technological advancement’s alleged impact on writing. According to these small minds, the impact of radio, phone, television, aircraft, and space exploration is so significant that it could change the nature of literature. How frivolous is such a thesis! It is enough to read merely the beginning of the second song of the Iliad to understand that the great blind one had no need for any TV waves or rocket ships to shift the narrative “camera” from the angry Zeus to the ground, and to the military log about the Trojan campaign. Aeschylus swept over the heads of thousands of soldiers and sleeping commanders to find the sleeping skull of Agamemnon, within which a dream was being conjured.

Let’s imagine an extraterrestrial being on whom we impart some knowledge about the Earth and then present two dramas, one ancient and the other modern, without indicating which is which. It is likely that after reading both, when asked to determine which preceded the other, this being might point to the ancient drama as a concoction of modern times and to the contemporary drama as something from antiquity.

The moment when the ancient Greeks suddenly enter the life of a person is akin to experiencing a great earthquake. To some, this happens during childhood. To others, this occurs deep into old age. Like all great convulsions, ancient Greek literature has the unsettling ability to strike us at any stage.

It is known that the ancient Greeks provided a sense of serenity for Voltaire and especially for Schiller and Goethe. If we are to believe his wife’s notes, this is not what happened with Leo Tolstoy. She berated him for continually thinking about his Greeks, whom she blamed for making her husband ill: “They bring only angst and indifference about today’s life. No wonder they call Greek a dead language.” Tolstoy himself never claimed that the ancient Greeks brought him turbulence and anxiety, but Countess Tolstoy was convinced that dealing with them was the same as dealing with residents of hell.

We know nothing of what disturbances the Greeks might have occasioned in Shakespeare’s soul. We do know that when he wrote his grimmest tragedies, Macbeth and Hamlet, he was as old as Tolstoy was when the Greeks “sickened” him. We also know that Tolstoy worshipped the Greeks and did not care much for Shakespeare—but let’s set these family quarrels aside.

Just like it does within one’s life span, the Ancient Greeks inevitably emerge in the life of nations. Seneca was one of the first bridges through which the Greeks of antiquity passed with their blinding lights. They landed in the European continent, and from there moved onward to illuminate the whole world.

This unexpected incursion brought humanity unprecedented new dimensions of thought and imagination. It brought hell, the wounded conscience, Prometheanism, fatality, duplicity, and shadows.

There has been much discussion about the echoes of Greek masters in world literature, beginning with Latin authors, then Dante, Shakespeare, and Goethe, and finally appearing in texts by Hölderlin, Hauptman, O’Neill, T. S. Eliot, and Sartre. There would not be an inferno without the earlier Greek models of hell. What would the bloodstains on the hands of Lady Macbeth look like without the earlier stains on Clytemnestra’s hands? What would the disturbed consciences look like, the broken sleep or the unsettling dreams, the glowing candlesticks in the middle of the night? What shape would these crimes have taken?

Despite some progress, much has yet to be explored. It is interesting, for example, to see how Shakespeare’s victim-kings, killed by those who aspire to their throne and lust for their women, are not so colorful when compared to the more intricate Agamemnon.

Shakespeare stands the victim-kings alongside their murderers and idealizes the former, which suggests that schematization is such an insidious disease that it can infect even a genius. Aeschylus, quite free from this ailment, gives us the anguish and sorrow of Agamemnon’s death while also reminding us of his previous atrocities. In Agamemnon we find both Hamlet and Duncan, the good kings, and Macbeth and Claudius, their killers.

We can still speak of Prometheanism, this tremendous strain on human relationships that does not allow humanity to rest. We can also keep exploring the indirect echoes of Aeschylian literature in writings that at first seem totally unrelated to his works. With the bloody chronicle of the Atreus, Aeschylus began the tradition of reporting the crimes and dramas that defile the homes of big families, a tradition that passed on from drama into prose, eventually making its way into masterpieces by Balzac and Tolstoy. What Aeschylus started in the Atreus, Balzac and Tolstoy continued in upscale Parisian neighborhoods and during the cold Russian winter.

–Translated by Ani Kokobobo

__________________________________

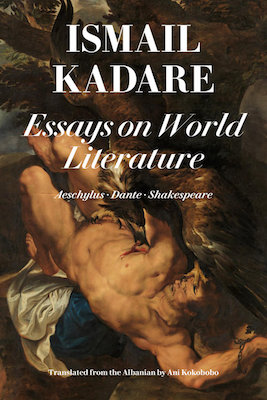

From Essays on World Literature: Shakespeare, Aeschylus, Dante by Ismail Kadare, courtesy Restless Books. Copyright Ismail Kadare, translated by Ani Kokobobo.

Ismail Kadare

Ismail Kadare is Albania’s best known novelist. He won the inaugural Man Booker International Prize in 2005; in 2009 he received the Príncipe de Asturias de las Letras, Spain’s most prestigious literary award, and in 2015 he won the Jerusalem Prize. In 2016 he was named a Commandeur de la Légion d'Honneur. His last book to be published in English, The Traitor’s Niche, was nominated for the Man Booker International.