The Straight Line From Slavery to

Private Prisons

How Texas Turned Plantations Into Prisons

A white man on horseback, holding a rifle, looked out over an expanse of cotton that stretched beyond the horizon. Four packs of bloodhounds lay on the edge of the field. One dog had gold caps on two of his teeth, a mark of distinction for tracking a runaway and bringing him back to the plantation. Black men were lined up in squads, hunched over as they pick. The white man couldn’t hear what they were singing, but he’d heard the songs before. Sometimes, as they worked, a man would sing out, “Old Master don’t you whip me, I’ll give you half a dollar.” A group of men reply in unison, “Johnny, won’t you ramble, Johnny, won’t you ramble.”

Old Master and old Mistress is sittin’ in the parlor

Johnny, won’t you ramble, Johnny, won’t you ramble

Well a‑figurin’ out a plan to work a man harder

Johnny, won’t you ramble, Johnny, won’t you ramble

Old Marster told Mistress, they sittin’ in the parlor

Johnny, won’t you ramble, Johnny, won’t you ramble

Old Marster told old Mistress to take the half a dollar

Johnny, won’t you ramble, Johnny, won’t you ramble

“Well I don’t want his dollar, I’d rather hear him holler”

Johnny, won’t you ramble, Johnny, won’t you ramble

One of the men, Albert Race Sample, was picking cotton for the first time. Throughout the course of his life, he’d shined shoes, worked the circus, shot craps, and cleaned brothel rooms after prostitutes, but he had never worked in a field. His only connection to cotton was that his white father, who used to pay his black mother for sex, was a cotton broker. Sample lined up in a row with the other men in his squad, picking the bolls one by one and dropping them into the 14‑foot sacks they dragged along. The white “bosses” assigned the fastest pickers to head each squad, making everyone else struggle to keep up. By the time Sample picked the cotton from two stalks, the rest of the row was 20 feet ahead of him. One of the bosses, known as Deadeye, walked his horse over to Sample and scrutinized his every move.

Sample grew up in his mother’s brothel. As a boy, he served bootleg liquor to the men who gambled there and had sex in his bed. He would practice his dice techniques on the floor, learning how to set them in his hand and throw them in a way that would make them land just how he wanted. His mom liked to play too. Once, in the middle of a game, she told him to fetch her a roll of nickels. When he told her he lost it, she slapped him in the mouth, knocking a tooth loose, and went back to her game. Sample caught a train out of town and survived on tins of sardines, food he stole from restaurants, and picking pockets at racetracks.

Picking cotton, like picking pockets, is a skill that takes time to master. Grab too much and fingers get pricked on the boll’s dried base. Grab too little and only a few strands come off. The faster Sample tried to pick, the more he dropped. The more he dropped, the more time he wasted trying to get the dirt, leaves, and stems out before putting it in his sack.

“Nigger, you better go feedin’ that bag and movin’ them shit scratchers like you aim to do somethin’!” Deadeye shouted.

Sample’s back hurt.

Eventually the bosses ordered the men to bring their sacks to the scales. The head of the squad had picked 230 pounds. One man had only picked 190 pounds, and Deadeye shouted at him. When Sample put his sack on the scale, one of the bosses, Captain Smooth, looked at Sample like he’d spit in his face. “Forty pounds!” Captain Smooth shouted. “Can you believe it? Forty fuckin’ pounds of cotton!” Deadeye got a wild look in his face. “Cap’n, I’m willing to forfeit a whole month’s wages if you just look the other way for five seconds so’s I can throw this worthless sonofabitch away.” He pointed his double‑barrel shotgun, hands trembling, at Sample and laid the hammers back. Those waiting to weigh their cotton scampered away.

“Like prison systems throughout the South, Texas’s grew directly out of slavery.”

“Naw Boss,” Captain Smooth said. “I don’t believe this bastard’s even worth the price of a good load of buckshot. Besides, you might splatter nigger shit all over my boots and mess up my shine.” Boss Deadeye lowered his shotgun. “Where you from nigger! I suppose you one’a them city niggers that rather steal than work. Where’d you say you come from?” When Sample attempted to answer, Deadeye shouted at him. “Dry up that fuckin’ ol’ mouth when I’m talkin’ to you!”

As punishment for his impertinence and unproductiveness, Sample would not be allowed to eat lunch or drink water for the rest of the workday. “As for you nigger, you better git your goat‑smelling ass back out longer and go to picking that Godamn cotton!”

The year was 1956, nearly a century since slavery had been abolished. Sample had been convicted of robbery by assault and sentenced to 30 years in prison. In Texas, all the black convicts, and some white convicts, were forced into unpaid plantation labor, mostly in cotton fields. From the time Sample arrived and into the 1960s, sales from the plantation prisons brought the state an average of $1.7 million per year ($13 million in 2018 dollars). Nationwide, it cost states $3.50 per day to keep an inmate in prison. But in Texas it only cost about $1.50.

Like prison systems throughout the South, Texas’s grew directly out of slavery. After the Civil War the state’s economy was in disarray, and cotton and sugar planters suddenly found themselves without hands they could force to work. Fortunately for them, the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery, left a loophole. It said that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude” shall exist in the United States “except as punishment for a crime.” As long as black men were convicted of crimes, Texas could lease all of its prisoners to private cotton and sugar plantations and companies running lumber camps and coal mines, and building railroads. It did this for five decades after the abolition of slavery, but the state eventually became jealous of the revenue private companies and planters were earning from its prisoners. So, between 1899 and 1918, the state bought ten plantations of its own and began running them as prisons.

Forced labor was undeniably productive. An enslaved person in an antebellum cotton field picked around 75 percent more cotton per hour than a free farmer. Similarly, Texas prison farms into the 1960s produced a higher yield than farms worked by free laborers in the surrounding area. The reason is simple: People work harder when driven by torture. Texas allowed whipping in its prisons until 1941. Other states banned it much later. Arkansas prisons used the lash until 1967. But even after the whip, prisons found other ways to make inmates work harder. The morning after Sample’s first day of picking in 1956, the guards sent him, along with eight other men, to a four‑by‑eight‑foot concrete and steel chamber to punish them for not making quota. The room was called “the pisser” and there was no light or water inside. A hole the size of a 50‑cent piece in the center of the floor served as the lavatory. The men’s panting breaths depleted the oxygen in the rancid air. “The nine of us writhed and twisted for space like maggots in a cesspool,” Sample recalled in his memoir. If someone took up too much space, a fight could break out. They stayed in the pisser all night, each taking turns lying down as the rest stood or squatted. In the morning they were brought straight out to the cotton fields.

Sample went back and forth between the fields and the pisser as the season wore on. When his cotton bags finally started to weigh in at 100 pounds, they gave him a different punishment: the cuffs. The first time he was subjected to this, a guard told him to get on the floor. He put a cuff link around Sample’s right wrist, closed it as tight as he could, and then stomped it tighter with his foot. He then looped the cuffs through some prison bars above Sample’s head and fastened them onto his left wrist. He was left hanging with his toes barely touching the floor. Other men hung alongside him; after an hour or so some of them began to groan. Pains shot through Sample’s arms and he bit his lip to keep from crying out. Inmates filed past the hanging men on their way to the mess hall, each avoiding looking in the direction of the ones being tortured.

“Texas prison farms into the 1960s produced a higher yield than farms worked by free laborers in the surrounding area. The reason is simple: People work harder when driven by torture.”

Eventually the lights were dimmed and the nighttime hours crept by. Around six hours in, one of the hanging men began violently jerking and twisting until he was facing the bars. He used his feet to push against them, straining to loosen himself from the cuffs. When it didn’t work, he bit into his wrists, gnawing at them like an animal in a steel trap. Another inmate called for a guard, who splashed the frantic man with water until he stopped. In the morning they were uncuffed and sent back to work.

As the season progressed, Sample became skinnier and skinnier.

The bosses regularly denied him meals as punishment for substandard picking. But after a dozen more trips to the pisser and several more rounds with the cuffs, his picking skills improved considerably. As one guard told him, “those miss meal cramps” have a phenomenal effect on the development of cotton picking speed.

![]()

It was in this world that CCA cofounder Terrell Don Hutto learned how to run a prison. In 1967 Hutto became warden of the Ramsey plantation, which was just down the road from where Sample had been incarcerated. Before running prisons, Hutto had been a pastor, studied history, spent two years in the US Army, and did graduate work in education at the American University in Washington, DC. There was little that distinguished the Ramsey plantation from the one Sample had been imprisoned on. Aside from the banning of the whip, the modes of punishment and labor were the same when Hutto began as they’d been when the state opened its plantation prisons in 1913. The main difference between Hutto’s plantation and Sample’s was scale: Ramsey was as large as Manhattan, twice the size of Sample’s plantation, and it had 15,000 inmates working its fields.

At Ramsey, Hutto learned how to think about prison as a moneymaking venture. Corners could always be cut to service the bottom line. Much in the way that slaveholders had selected certain slaves to manage and punish the rest of their chattel, Hutto learned the Texas policy of empowering certain inmates to manage and punish other prisoners. These inmates ran the prison’s living quarters with brutal force, sometimes wielding knives to keep other inmates under control. By using them, Hutto could save money that would otherwise be spent on guard wages.

“Hutto learned how to think about prison as a moneymaking venture. Corners could always be cut to service the bottom line.”

Hutto and his family settled into their plantation home in 1967. “All You Need Is Love,” by the Beatles was a new hit, and the Huttos might have listened to it in their living room while their “houseboy” cooked and served them. The houseboys were prisoners, almost always black; they made the beds, cleaned, and babysat the children. Personnel at the Texas Department of Corrections considered the provision of convict servants to be an indispensable perk that guaranteed it could “attract the type of men who could do the job.”

The regulations of houseboys echoed the fears of slaveholders toward their house slaves. Policy prohibited Hutto’s wife from conversing with houseboys or being overly “familiar” with them. Houseboys were prohibited from washing her underwear. Joking with houseboys was banned, as was allowing them to sit with the family to listen to the radio or watch television for fear it would lead to impertinence. Hutto would live as the master of this and other plantations for a decade, distinguishing himself by making some of them more profitable than they’d been before he took charge. A handful of years later, after leaving the plantations, he would open the latest chapter of a story that goes back to the foundation of this country, wherein white people continue to reinvent ways to cash in on captive human beings. He would create Corrections Corporation of America.

![]()

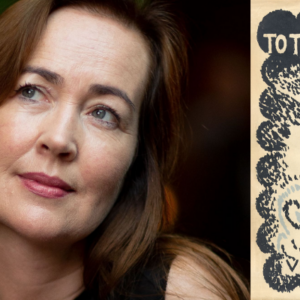

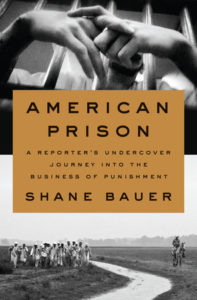

From American Prison by Shane Bauer, published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2018 by Shane Bauer.

Shane Bauer

Shane Bauer is a senior reporter for Mother Jones. He is the recipient of the National Magazine Award for Best Reporting, Harvard’s Goldsmith Prize for Investigative Reporting, Atlantic Media’s Michael Kelly Award, the Hillman Prize for Magazine Journalism, and at least 20 others. Bauer is the co-author, along with Sarah Shourd and Joshua Fattal, of a memoir, A Sliver of Light, which details his time spent as a prisoner in Iran.