The Storykiller and His Sentence: Rebecca Solnit on Harvey Weinstein

“To be a woman is to be forever vigilant against violence.”

There was a man who was in charge of stories. He decided that some stories would be born, expensive, glamorous stories that cost more than a hundred minimum-wage earners might make in a hundred years, filmy stories with the skill of more hundreds expended so that they would slip in like dreams to the minds of millions and make money, and he made money and the money gave him more power over more stories.

There were other stories he decided must die. Those were the stories women might tell about what he had done to them, and he determined that no one must hear them, or if they heard them they must not believe them or if they believed them it must not matter.

His work to let stories out was public, and he was on many stages accepting many awards for them and at many parties exerting influence and handing out favors and malevolent disfavor. His work to keep stories in was also strenuous, expensive, and masterful in a way, because it worked: perhaps he took particular pleasure in stifling the stories of women who were otherwise so visible, so audible, who were in those stories we all saw, in making them dolls who said the words of others, the words that brought him awards and a fortune, and in preventing them from telling their own stories, the stories of what kind of monster he was, of what felonies he had committed.

He sat like a malevolent god, deciding whose voice and vision would live and whose would die, or like a king with courtiers to produce this story in a shower of money and networking and to kill this other story with nondisclosure agreements that also required showers of money, sometimes directly out of his business-partner brother’s pocket to keep them off the company records, or he spent political capital to persecute and discredit the women who had stories of what he had done, and to drive them out of their profession, their vocation, and their living, to push them over a cliff at the bottom of which was isolation and inaudibility.

There were grips and gaffers and best boys, sound engineers and editors and acting coaches to make the stories; there were spies, lawyers, insurance companies, underlings to unmake the other stories, some of them skilled actors themselves, and they went even after the newspapers and journalists who got wind of those stories. The whole society was complicit in allowing a system of silencing to exist, even a formal legal contract called a nondisclosure agreement, which meant that her (and sometimes his or their but so often her) story would be silent forever. One of his victims was not allowed to talk even to her family or therapists about what happened and when she finally broke her long silence she spoke of what torment it was and joined a congresswoman in sponsoring legislation; many of them at last violated their NDAs to speak, and the complicity of celebrity lawyers and the legal strategy for strangling stories, the silence for sale, looked bad when it was dragged out in the light of day, and some states passed laws limiting them, at least as they pertained to sex.

“He who controls the past, controls the present,” wrote George Orwell in 1984, “he who controls the present controls the future.” He who has the story has the power; she who has no story, not even her own, has no power.

It seems as though there are always these stories about women, the insinuating sneering stories, the stories in which women are unforgivable for things men are forgiven for as soon as they’ve done them.

And so he clawed his way through the years, destroyer and generator of stories, sitting like a judge over them all, shaping the public imagination, both with what we saw and heard and what we did not, and what we do not know is always the heavier side of the scale, and those of us who find ourselves there find ourselves silent, mute, gagged, our stories murdered before they can go out into the world, or our stories stillborn because they died at birth, because we did not dare to speak or because we despaired that if we spoke our words would not do the work words should do in the world—connect us, weave us into the society—but would endanger us or make them ostracize us. And so the scale dipped low with the weight of strangled, murdered, stillborn, stunted stories. The stories sat inside, like impacted wisdom teeth, like ectopic pregnancies, something that needed to come out. But they could not because the women with stories were not in charge of stories.

In the middle of 2017, this powerful man somehow decided (or a minion decided and invoked his name) that I should watch a film or rather a screener—an early release DVD—of one of the stories he had put out into the world. I knew almost nothing about the man, but I began to be pestered to watch the story. Here’s how the letter that was supposed to be from him described it: “the gripping story about a young girl’s murder on a Native reservation… I think you’ll find it intensely chilling. I’d love to hear your thoughts after you’ve had a chance to screen. All my best, Harvey.”

I didn’t watch it. I’m sick of the pretense of sympathetic interest in movies and books and the rest that murder women over and over, and too many native women are being murdered without adding a fictional murder to the spatter pattern. I see women die violently every day. I’m getting weary of it. Sometimes I take a screenshot of the front page of the Guardian and ask people how many items have to do with violence against women or men who have abused women, and sometimes it’s most of the lead stories. Sometimes this violence is the story, or sometimes someone who has a record of abusing women is just running for president or is president and the story is about something else, but their power reminds you of your powerlessness if you’re a woman, or the story about Wexner selling control of Victoria’s Secret on February 20 is a reminder of his mysterious financial relationship with pederast-pimp Jeffrey Epstein, who used the relationship as well to pretend to recruit girls as models.

But also directly in the news are gruesome stories—a few weeks ago I ran into news about an American man who dismembered his ex- with a saw, an Australian ex- who did so by pouring gasoline over her and the kids and burning them to death and a Mexican man who skinned his ex- like a rabbit after murdering her. And right after that there was a day when I opened an envelope a publisher sent me (please stop, publishers) to find a memoir about a woman whose sister had been murdered, which I decided not to read, and then I sat down next to a woman on the ferry reading the book by James Ellroy about his mother being murdered, with apparently a picture of her corpse on the back cover.

I wasn’t looking for these stories; they’re there all the time because women are getting killed all the time; I’m just the anomaly who’s been noting their frequency for the last 30 years or so, and who has felt impacted by that. I am the Ancient Mariner of violence against women, because for 35 years I’ve been trying to fix people with my glittering eye and make them listen.

And then I published a book about the intensely chilling experience of being a woman in a world where so many men harm women and so little is done to stop them and the stories I told prompted women to tell me new stories about when they too were young, imperiled, and alone in that peril. We have a word, voiceless, that is a misnomer, because we all had voices; we just had no one to listen to them, and so we need another word—something like listenerless—for that condition. I wrote about the way that I was menaced so often and so convincingly and was so traumatized that I had intrusive fantasies in which I was assaulted, as I had been in real life, and in the fantasies I was more successful at violence than my assailant and killed him, and so I killed over and over in the dankest years of my fear. It wasn’t the only fantasy I had when I was so haunted during my years as a target. I wasn’t the only one who had fantasies either.

Something changed, and the forces that prevented them from telling their stories were overcome by those who willed those stories into the room and their own fury to speak.

A woman told me, in response to the book, that she imagined over and over again, in the same mode, how to go numb and disassociate when she was raped—she thought it was likely she would be and so this was the unspeakable way she prepared for it, and by unspeakable I mean literally: she spoke to no one of how though her body had not been invaded by a penis, her mind had been invaded by the likelihood of it. One of the things I wanted to do with my book is to argue that we have been telling the story of violence against women wrong.

We treat it as a sort of binary: either direct literal physical violence has happened directly personally to you or it hasn’t, and if it hasn’t you don’t have a story and you haven’t been harmed. But we have. We all have. To live in a society that puts a target on your back because of your category is a hard thing indeed, and to live in a society that put the target there and then doesn’t want to hear about it, is harder yet, and that’s exactly where we have been all along. To be a woman is to be forever vigilant against violence, which means thinking about it all the time and making decisions based on the possibility. (And of course the same is true of being black or queer or trans.)

I wrote a book about what it means to be voiceless, or listenerless, and realized afterward that I was writing about that all along and also writing about what it meant to be the opposite: someone who was so amplified and fortified that he could shout down facts and truth and evidence and make stories die or never be born or go away unbelieved. Storykillers. The day before my book came out, women in Mexico marched on strike to protest the epidemic of femicide there. And then the day after my book came out, the man who sat like a god, a judge, a king calling some stories into being and sending ex-Mossad spies to hunt down and kill other stories was sentenced, and that so many thought the day would never come says a lot about the dim expectations of women even in this age.

It came a week after a woman who ran for president resigned herself to defeat and stepped out of the race, and the experts said that it was not that not enough people wanted her to be president. It was that they did not believe other people wanted a woman, this supremely brilliant and empathic and innovative woman, to be president and so they voted down their own desires, dampened by fear of others. They did not believe others would let us have what we wanted and so we did not get it, and it was also dampened down by stories that were not particularly true but were told so often too many people thought they were, and too many of them who did not have time to check the stories had time to spread them.

It seems as though there are always these stories about women, the insinuating sneering stories, the stories in which women are unforgivable for things men are forgiven for as soon as they’ve done them which is part of why they do them. Sometimes it seems the unforgivable thing is just that they’re women. She was, too, a woman who had just confronted a man—the ninth richest man in the world—on national television about the 64 nondisclosure agreements associated with him and made him allow 3 of the 64 to speak after all. The current president and this man who would be president before she skewered him had a lot of NDAs to their name. There are storykillers everywhere.

It came less a week after the young man who had helped to expose the crimes of the king of the storykillers threatened to leave his publisher in protest because they were going to publish his father’s book and his father from whom he had long been estranged was a storykiller too, a man who had been smearing his former partner, the young man’s mother, for decades and smearing the daughter who told a very credible story from childhood into adulthood, that he had molested her. So many people at the publishing house walked out in protest—younger people, I heard, people who were sick of the old stories and in solidarity with the new stories—that the book died, at least in that house. Because there are stories built out of silence and lies and the stopping of others’ stories too. There are stories that are all about storykilling.

And then the king of the storykillers was sentenced to 23 years in prison, which means if he serves all his time, he will be 90 when he gets out. He was handcuffed to a wheelchair, having declined physically, as though his fall from power had been a physical collapse or perhaps to try to spark a story with sympathy for him in it. He bled with sympathy for himself and people like him, “I was the first example,” he said, of men whose crimes finally came to light, “and now there are thousands of men who are being accused.” That the great majority of them are being accused because they did the things they are accused of is something too terrible to grasp for the old story kings, too damaging to their own story about themselves, even when they themselves are storykillers and sexual predators.

“I’m worried about this country,” the Guardian reported the storykiller as saying, because there are “thousands of men and women who are losing due process” after being accused. “I’m totally confused. I think men are confused about these issues.” That perhaps as many as a hundred women didn’t have due process because he was as much a storykiller as a literal assailant and groper and harasser and rapist seemed to be an idea he could not imagine. Because this man who had made so many of our stories, the ones we paid to see, the ones that got the Oscars, could not imagine the stories of these women, could not imagine their stories about him, could not imagine.

I saw little boys jeering and mocking the other day, and I began to wonder if this behavior so common in boys and young men and sometimes older ones (and yes sometimes in girls and women, but far less so), is practice in being without empathy. That game of taking satisfaction and seeing others’ discomfort and distress as your own victory is practice, sometimes on a small scale of insults, sometimes on the larger scale of bullying, of a self-aggrandizement by the annihilation of others, a disconnection, a death of empathy. This does not mean that most of them will go the lengths the storykiller did, but it does mean that the behavior is an extreme version of an everyday thing.

“He is baffled at finally being held accountable,” one of the victims said. It is not a story he imagined; it is a story he cannot comprehend. But he was no longer in charge of stories. Something changed, and the forces that prevented them from telling their stories were overcome by those who willed those stories into the room and their own fury to speak. And then he became the protagonist of the last story he ever imagined, and his story is now a single interminable sentence, and that 23-year-long sentence is about a storyteller who failed to imagine their stories or the end of his own.

___________________________________

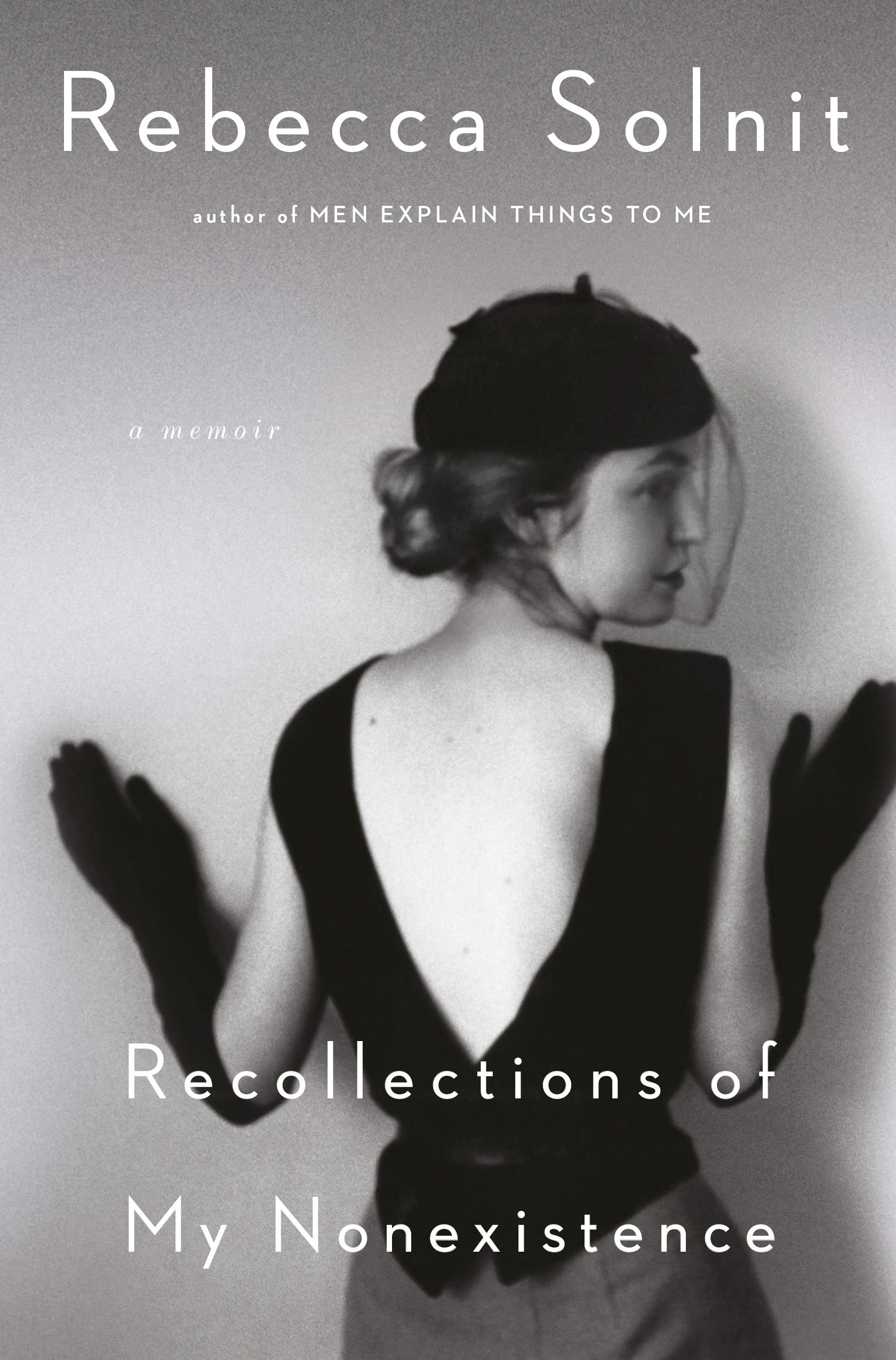

Rebecca Solnit’s Recollections of My Nonexistence is available now from Viking.

Rebecca Solnit

Writer, historian, and activist Rebecca Solnit is the author of more than twenty-five books on feminism, western and urban history, popular power, social change and insurrection, wandering and walking, hope and catastrophe. Her books include this year’s No Straight Road Takes You There, as well as Orwell's Roses, Recollections of My Nonexistence; Hope in the Dark; Men Explain Things to Me; and A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities that Arise in Disaster. A product of the California public education system from kindergarten to graduate school, she writes regularly for the Guardian and serves on the boards of the climate groups Oil Change International and Third Act.