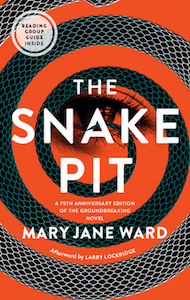

The Story Behind The Snake Pit, Mary Jane Ward’s Dark Comic Masterpiece

Larry Lockridge on His Cousin’s Novel and His Family’s History of Mental Illness and Literary Talent

Mary Jane Ward received a letter from Harold Ober, her literary agent, on July 29, 1937. “Dear Miss Ward, I am enclosing a royalty statement from E. P. Dutton & Company on THE TREE HAS ROOTS for period ending April 30, 1937 showing royalty amounting to $2.85 due Oct. 1st.” Her debut novel, published early that year, received lengthy, positive reviews in The New York Times, The Chicago Tribune and elsewhere, but she had received a larger sum, $10.00, for a winning meatloaf recipe, published in the Chicago Daily News. It was an untested recipe. She later claimed that she and her husband couldn’t afford the chopped meat for it.

This is a Depression-era story. The reading public then took little interest in a novel set in academe that doesn’t feature glamorous deans or senior faculty in mahogany-lined quarters but a janitor, a secretary, and low-level functionaries. It ends when a worker guilty of sexual harassment burns down the university chapel. Could such a novel lift spirits of the dispirited in the late 1930s? And Miss Ward’s recipe was not for crab-stuffed filet mignon with peppercorns but the most plebeian of dishes, risky to order in company of food snobs.

Her second novel published by Dutton, The Wax Apple, again highly praised by prominent critics in 1938, didn’t fare much better. It features an upstairs/downstairs cast of lower-middle-class folk in a dreary suburb of Chicago, tells of a young woman widely suspected of losing her virginity when she was only making out on a family couch, and ends with a murder-suicide. The New York Times reviewer wrote that Mary Jane Ward “has an astonishing sure insight into the lives of humble people. She knows her lower middle class—what clothes they wear, what slang they affect, what shibboleths and pretenses attend their struggle to better themselves.” But John Mccrae, Jr., president of Dutton, wrote her: “We did lose money on THE TREE HAS ROOTS and it is not likely that we will earn a cent of profit on THE WAX APPLE.” He added that her novels showed promise.

She kept on writing, as she would have with or without encouragement.

In 1945 she sent another novel to the Harold Ober Agency and got this reply: “Dear Mrs. Quayle: I am sorry to make a negative report about a book of yours, but Mr. Ober and I have been discussing [“The Snake Pit”] and the problems this book presents and have decided it would be wiser not to offer it. I think you could hardly have picked a more difficult subject to write about and neither of us feels that you have been really successful with it. Also books about insanity or mental breakdowns are not popular at best and the recent publication of Carlton Brown’s Brainstorm has, I am afraid, killed the chances for another book for quite a while. It seems to me if you are going to write a book of this sort subjectively, the reader must be sympathetic toward your principal character. Unfortunately my own feelings were composed more largely of irritation than of sympathy. . . . Sincerely yours, Ivan van Auw, Jr.”

This is a cautionary tale for the publishing industry. Today all that is remembered of Ivan van Auw, Jr., is that he is the agent who rejected The Snake Pit.

To be fair, I’ll add that Mary Jane Ward had temporarily lost her nerve upon submitting the manuscript. “I had already named it The Snake Pit but had decided it seemed too dramatic.” Van Auw stared at a manuscript discreetly titled “V. Cunningham, Juniper Hill” after its heroine, Virginia, and the mental institution where she is incarcerated. He was unaware that the novel is autobiographical and that his irritation was directed toward the author herself. Dejected, Mary Jane was inclined to shelve the manuscript but her indignant husband Edward Quayle wouldn’t hear of it. They submitted it next to James Putnam at Macmillan, who praised the novel highly but went on: “In light of all this, you may well wonder why we are declining the book. . . . As you know, Brainstorm has had considerable success recently and in our opinion this type of book can only be published about every few years.”

Metamorphosis is the silent premise of the novel from the beginning, since Virginia has herself turned into someone she doesn’t recognize, her memory bank partially voided and uncertain who and where she is.

Putnam’s praise gave them encouragement enough to try Random House through Mary Jane’s friend Irene James, an aspiring writer acquainted with editor Robert Linscott. Linscott was enthusiastic as was Bennett Cerf, the publisher, accepting it immediately. But Cerf was worried. He spent “a whole afternoon trying to persuade her to change the title, because, I said, ‘Women buy most of the novels—and they hate snakes!’ Thank God, she told me to go to hell. Now, of course, snake pit is part of our language.” Within weeks of its publication in early 1946, The Snake Pit was first on the Chicago Daily News’s best-seller list and second on The New York Times’s, was a Book-of-the-Month Club Dual Selection, had sold more than a million copies in hardcover, was on its way to Hollywood, and was soon translated into sixteen languages.

*

Fairmont, Indiana, is famed as the birthplace of James Dean, but in 1905 Mary Jane Ward was born there also, daughter of a jewelry dealer and a suffragette. She spent her youth in and around nearby Peru, Indiana, living for a time in a house rented out by Cole Porter’s family. Irene James describes meeting her at age thirteen: “She looked like a child out of certain English novels, not beautiful exactly but strangely arresting. There was that about her which stirred the imagination: the magnificent thick dark auburn hair and the quickest, most oddly penetrating yet friendly brown eyes in the world, and even then the lovely low-pitched voice. She was what grownups describe as an extraordinary child, with a talent both for the piano and for drawing, and with many nickel notebooks filled with stories.”

From the age of nine Mary Jane studied piano, playing her own compositions at Lyon and Healy Hall in Chicago. Entering Northwestern University in 1923 and majoring in Latin, she heard a talk by Theodore Dreiser, whose literary realism would greatly influence her. She wrote music and theater reviews for a local Evanston newspaper, was its short story editor and published her own stories under pseudonyms when she fell short of the quota, and became engaged to a premed student, Rockwell Ryerson, who died of Bright’s disease soon afterwards.

One of Ryerson’s friends, Edward Quayle, an undergraduate recently transferred from the University of Chicago, offered consolation. Friendship turned to romance and they eloped in 1928. So began a steady marriage of fifty-three years, during which they saw eye to eye on most matters, including religion as Unitarians and politics as devotees of socialist Norman Thomas. Quayle had ambitions of his own—playwriting and painting—but, frustrated, eventually packed them in, working as a statistician in the safety department of a cement manufacturing company. “As it turned out: Mary Jane was my vocation.” Until the end of her life, he served as her first reader, advisor, and caregiver. “Mary Jane was my life and when hers ended so, in essence, did mine.”

In keeping with the tradition of midwestern writers who escape to New York City, Mary Jane and Edward took up residency in a small apartment on Waverly Place in the fall of 1939, where they frequented the theater, buying the cheapest seats, often one dollar, twice the fifty cents they had spent in Chicago. They joined the War Resisters League in 1940 and moved briefly into a communal apartment with other resisters in Queens before settling into a small apartment at 191 West 10th Street.

In spring 1941, while her husband Edward Quayle was working for low wages at a local hotel, Mary Jane began to exhibit what at first seemed merely a case of nerves, worried about money as in Depression days and having insomnia at the prospect of an anti-war speech she was to give at a New Jersey retreat. Soon thereafter, writes Edward, “she became incoherent and I had to take her to a psychiatrist, wife of a doctor our Trotskyist friends recommended. She told me she tried to get MJ into an experimental psychiatric hospital but that her case was too ‘classic,’” so she was committed to Rockland State Hospital, seventeen miles north of Manhattan, on June 5, 1941, and released eight and one-half months later on February 22, 1942. Edward didn’t have the funds for a private institution. A Depression mentality regarding money will pervade The Snake Pit as it did the earlier Dutton novels. Virginia worries that her husband has spent too much on the roast chicken he brings for a picnic and tries to pry out how much her keep is costing him. He averts his eyes. Mary Jane’s dedication of her novel, left unprinted, was “to those who have no credit at the store.”

What presented as incoherence is sometimes called “word salad,” an unsavory term for a breakdown of normal syntax and vocabulary often seen at the onset of schizophrenic episodes but sometimes in manic episodes of bipolar disorder. Mary Jane writes that the onset of her illness “was sudden, acute . . . quite without warning.” “Nothing she said made any sense to me,” said Quayle, who underscores how terrifying the onset of mental illness can be to all parties: one’s most intimate companion cannot make sense of what you are saying. During her four hospitalizations, in 1941, 1957, 1969, and 1976, all of which first presented with verbal incoherence, Mary Jane was routinely diagnosed with schizophrenia, as was her younger sister Charlotte.

Mental illness may run in families but have a quite different mooring in psychology and life experience, and present in totally different ways.

Whether or not this would survive the current revisionism that sees mood disorders where earlier psychiatrists saw schizophrenia, I cannot say. It’s hard to put a novel on the couch, but readers of The Snake Pit, whether professionals or amateurs in matters psychological, can make their own diagnosis in response to the disturbed mind that Ward surrounds us with from the beginning. It’s not much of a spoiler to say that the novelist herself doesn’t give us one. Readers are simply thrown into the mind of Virginia Cunningham, with no firm contexts from a narrator.

When the film adaptation was about to be released in late 1948, the editor of the mass market paperback publisher Signet told Bennett Cerf that Mary Jane should cut the first chapter. Readers would find it confusing and might not read on. But she again stood her ground, saying that the first chapter was every bit as important as the last.

Signet relented and printed the whole thing.

There are many other novels set in mental institutions or featuring a mentally ill protagonist, most of them postdating The Snake Pit and some influenced by it, but this novel remains unique. A case needs to be made for Mary Jane Ward’s novel, long out of print until its publication by Library of America. I had read it a number of times over the years, but a surprising comment that begins her critique of the film script opened it up for me in a new way and distinguishes it from others of this subgenre. “The novel is primarily an adventure story. The protagonist’s adventures in a mental hospital are as strange and weird to her as Alice’s in Wonderland.” Readers identify with Virginia in her ordinariness, “forced to see the possibility of someday having to go through a similar adventure.” With Lewis Carroll in mind, the reader finds the bizarre first chapter no longer simply confusing and pathetic but unnervingly funny. Through to the end, the novel is a dark comedy of strange creatures and misadventures.

The Snake Pit as a rewrite of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland accounts for the mix of childlike bafflement, kindness, and pluck in Virginia as she encounters creatures almost as odd as those who pop up without warning in Wonderland, both amusing and scary. Parallels in episodes and themes are striking. Just as Alice goes down the rabbit hole and encounters the Cheshire Cat, the Queen of Hearts, the Gryphon, and the Mock Turtle, so Virginia descends into a snake pit and joins a Mad Tea-Party of the “crazy,” the word most off-limits at Juniper Hill. We first find Virginia sitting on a park bench hearing the pesky voice of a man asking her if she hears voices. The sound of a brook changes his voice into that of a small boy. “She tried not to look, but at last her eyes turned irresistibly and, with horror, saw him a girl.” In Wonderland the Duchess gives Alice a baby who turns into a pig.

Metamorphosis is the silent premise of the novel from the beginning, since Virginia has herself turned into someone she doesn’t recognize, her memory bank partially voided and uncertain who and where she is. She and other inmates are first defined by which ward they inhabit, and Virginia will inhabit many, noting marginal differences such as availability of toilet paper and which ward has food worse than which. Some episodes are painfully funny enough for Wonderland. She sits at dinner with the ladies chanting “Save some for Virginia,” only to pass her at last a virtually empty bowl. She can never learn the difference between a wet dry mop and a dry wet mop. She plays bridge with the ladies and “you could change trumps any time you felt like it. . . . A trick might consist of five cards, seven, three, one or none. However you felt.” In an asylum the patients are anarchists while the staff attempts to impose rules. In Wonderland there are no rules at the Queen’s croquet ground, “or, if there are, nobody attends to them.”

Mary Jane complained to producer-director Anatole Litvak that the film script of The Snake Pit was lacking in humor. “When we laugh at the antics of the insane we can be laughing in sympathy. In our hearts we know we are laughing at ourselves. What humor the novel has was put in deliberately to provide the readers with relief and to strengthen reader contact.” Here she prevailed, if only in part. Litvak had her meet with the scriptwriters, Frank Partos and Millen Brand, to get more humor into the script. The small character roles invite laughs, and Virginia as played by Olivia de Havilland has a degree of saving humor.

The most striking parallel between The Snake Pit and Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is that just as Alice is brought to trial for stealing tarts, maybe to be beheaded, so Virginia, having been fearful that she is being electrocuted during “shock” treatments and drowned while being tubbed, is brought up for trial at “Staff.” This is the group of doctors who will interview her and decide whether or not she is well enough to be released or, as she fears, punished further. Virginia feels guilty, but for what? At her first meeting with Staff, she bites the finger of a seeming accuser but has no memory of it.

Alice awakens at the end as from a nightmare, just as Virginia is finally released to the custody of her husband, Robert. The questionable idea behind the curative power of a snake pit is homeopathic and paradoxical: “an experience that might drive a sane person out of his wits might send an insane person back into sanity.” Confronting others even more insane than she is a shock treatment of sorts that gives Virginia the hope that she could return to sanity. Whether or not she has recovered by the novel’s end, readers may decide for themselves.

In someone for whom the center doesn’t hold, other people—“they”—are insubstantial and disappearing. Virginia makes acquaintance with poignant, fair-haired Grace on the park bench at the beginning, and we feel a friendship may be underway. Affable Grace seems headed toward recovery and a return to her career as journalist. But she disappears, taken to a different ward, and when much later Virginia meets up with her, Grace is wearing a straitjacket and is totally silent. She glares at Virginia menacingly. What has happened to Grace is a blank, but we know it cannot be good. As she moves from ward to ward, Virginia briefly encounters a series of odd ladies in mere cameos, soon gone.

The most insubstantial major character is Dr. Kik himself, source of the pesky male voice at the beginning asking if Virginia hears voices but not himself literally present. Near the end we hear that he has compiled a large file on Virginia but has made only rare appearances, the first not until near the end of Chapter Seven, almost halfway through the novel. Virginia knows him mainly through interaction with her husband, who trusts him, often telling her that Dr. Kik is pleased with her progress. Dr. Kik is a committed psychoanalyst, but readers never find Virginia on the couch dealing with the transference or speaking about her childhood or the trauma of losing her first fiancé, Gordon. Psychoanalysis is given the heave-ho when she and Robert find Dr. Kik’s diagnosis simply ridiculous. (Mary Jane struck the words “Dr. Kik is crazy” from her typescript.) What keeps Virginia from going down the snake pit forever is less Dr. Kik’s dubious treatment than the constancy of her husband. But even Robert remains shadowy in a world of shadowy characters. Evidence of Virginia’s pathology is the seeming unreality of others, even as she often feels intense sympathy toward them.

A second and related critical point that distinguishes this novel from others of its kind is how it discards much of what creative writing students are often taught about the need for a consistent narrative point of view. Though all is processed through the mind of Virginia Stuart Cunningham, the use of pronouns shifts unnervingly from “I” to “you” to “she”—from first person to second to third—and back again, often within a couple of paragraphs. Examples are unnecessary: readers will find them everywhere in the novel’s first half. An Amazon reviewer finds this “disconcerting” and awards the novel only four stars. But she goes on to say with insight that the novelist may have done this purposefully “in order to establish Virginia’s feeling of constantly having the world tilt around her.” What to some readers may be disconcerting will be, to others, the principal vehicle for cohabiting the consciousness of Virginia.

Clinical depression doesn’t insist on schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

The process of “stationing” is portentously called “deixis” by psycholinguists and narrative theorists. Readers of a narrative are led to a center of consciousness within a scene, often through use of pronouns and demonstratives that station consciousness, creating a plausible representational world where “I” is distinguished from “you” and “she,” and “this” from “that.” But remarkably there is no stable deictic center in Virginia in the early chapters. The representation of her mind shifts from one pronominal station to another, leaving us with little sense of a single narrator. Knowing well what she is doing here, Mary Jane Ward creates a representation of mental instability on the level of basic linguistic construction. Virginia isn’t clear who or where she is, maybe even if she is. But as she gradually gains greater control over institutional powers poised against her—like Houdini, outwitting nurses who are packing her in wet sheets—there is less deictic shifting, more a progression to stable third person narration.

I know of no other mainstream novel with such a pointed undermining of deixis. This is its formal originality and one rationale for admission into the academic as well as popular literary canon, for what instructor wouldn’t enjoy holding forth on deixis? The term would find its way into every classroom laptop. Mary Jane probably didn’t know the term but sensed how to make powerful use of its suspension, a linguistic innovation that coexists with the plain prose style and lack of rhetorical inflation we often associate with Jane Austen.

*

I’ve been referring to Mary Jane and Edward, not Ward and Quayle, because I knew them personally as Mary Jane’s double second cousin once removed. I saw them regularly from the age of four on. Mary Jane is a major figure in my biography of my father, Shade of the Raintree: The Life and Death of Ross Lockridge, Jr., Author of Raintree County. Nine years older than my father, she had many encounters with him when he was a boy still living in Indiana. They reconnected in 1946 after the publication of The Snake Pit and the acceptance by Houghton Mifflin of his unagented debut novel, not a dark 278-page tale of confinement but an expansive 1,060-page contender for Great American Novel, ostensibly affirmative but with a dark underside of its own. Their lively, hectic correspondence mostly concerned how to deal with publishers, lawyers, the press, and movie prizes. They endured lots of publicity about how these Hoosier hayseed cousins had become the season’s foremost literary celebrities.

Despite the striking parallels in their careers, there was an instructive difference. Ross Lockridge, Jr., was a study in what Mary Jane Ward was devoting much of her career to redressing—the shame that attends mental illness.

He was even-tempered throughout his life, if at a high pitch and intensely focused, and exhibited no signs of schizophrenia, depression, or bipolar illness. But he went through a period of grandiosity soon after his novel’s acceptance, thinking he had indeed written the Great American Novel. He and the editor-in-chief at Houghton Mifflin got into an epistolary battle over how to split up the MGM Award, billed as the world’s largest literary prize ever but really only a movie contract. He strongly felt that Houghton Mifflin, which he had regarded as family, was cheating him. Authors should never regard publishers as family.

He fell into a deep depression upon “throwing in the towel” to Houghton Mifflin on the MGM monies, October 21, 1947, precisely dated by my mother. She saw all vitality go out of him that morning. With no history of depression, he was baffled by what had happened to him and thought maybe something was organically wrong with his brain, not just his mind. Many other factors internal and external—a pointed convergence of them as I’ve written—entered in besides the triggering contract dispute. He remained articulate, no word salad, and no evidence, only lots of counterevidence, that he was either schizophrenic or bipolar.

But he had become deeply ashamed of his novel, prominently condemned by clergy as obscene and blasphemous. And because so much of himself had gone into it, he felt the humiliation of self-exposure. He said to his wife, “How did I ever think I could get away with writing such a book?” That it was a best seller made matters only worse, spreading his disgrace to all corners. He was ashamed of the illness itself that writing and getting the novel published had brought on. He could never have imagined that he, of all people, would have a “nervous breakdown.” Unlike Mary Jane, he did not publicly acknowledge his struggle with mental illness.

The poignant irony is that Mary Jane Ward was by that time already known as a major figure in mental health reform. Though working for improvement of mental health facilities, her greater passion was to make mental illness no longer a source of shame. “People go to a psychiatrist as secretly as they go to an abortionist.” “If The Snake Pit does anything to help people to see that mental illness is indeed an illness and not the result of a malicious attempt on the part of the patient to disgrace his friends and relatives, I’ll be very pleased.” Her mother was appalled that she would attach her own name to the disgraceful novel. And at first Mary Jane disclaimed any autobiographical element, writing in a book jacket blurb that “none of the characters of The Snake Pit ever existed in real life.” No good at concealment, she soon outed herself.

She saw my parents twice during my father’s six-month depression at her and Edward’s temporary new residence, a dairy farm near Elgin, Illinois, upon my parents’ own journey to and from Hollywood. Observing him shuffle around and duck upstairs, she told my mother that it was just “a case of nerves,” he would come out of it after a good rest. She tried to get him into a Chicago hospital for recuperation, but he was set upon getting back to his hometown.

Shortly afterwards, on December 23, 1947, he entered Methodist Hospital in Indianapolis under an assumed name. Such was the shame that attached to mental illness. Here, he was again underdiagnosed as suffering merely from “reactive depression,” not major or clinical depression. Even so he underwent electroconvulsive therapy like Mary Jane, so ineptly administered that he didn’t fully lose consciousness.

Fearing more treatments beyond the three already endured, he talked his way out and was discharged as “recovered” on January 4, 1948, one day before publication of Raintree County.

Clinical depression doesn’t insist on schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. He never recovered and took his own life by carbon monoxide poisoning the evening of March 6, 1948, just as Raintree County topped the nation’s best-seller lists. Besides the MGM Award, his novel had been excerpted in Life magazine and, going Mary Jane one better, was the Main Selection of Book-of-the-Month Club for January 1948. The reviewer for The New York Times wrote that Raintree County is “an achievement of art and purpose, a cosmically brooding book full of significance and beauty.” He heard only the pans. At age thirty-three, Ross Lockridge, Jr., left his wife and four young children. I was five years old at the time.

When Mary Jane invited me to join her for lunch at the Ritz Carlton in 1967 upon donating her papers to the Special Collections at Boston University, she told me she was convinced my father had not died a suicide. He was absentminded and always fumbling with his keys. Listening to the high school regionals over his car radio, he must have left the engine running in the garage apart from the new family house in Bloomington and passed out just as he was exiting the front seat, where my mother found him.

My mother had never confided to her or to me the fact of an attempted family cover-up of the suicide. I couldn’t then contradict Mary Jane but said only that my mother had never encouraged her children to think it an accidental death. In fact, she had found her husband not in the front seat as reported on page one of The New York Times but in the backseat, with a vacuum cleaner hose attached to the exhaust pipe. Front seat, backseat? Details, details. For me the difference was apocalyptic. His was not an impulsive act but a calculated suicide. My aunt Lillian Lockridge, trained as a parole officer, had beaten the police and fire department to the scene and disposed of the death paraphernalia.

She quickly concocted the story about the front-seat exit. She sensed the shame that the suicide would bring on the family, compounding the shame of the mental illness that led to it.

It wasn’t until early 1989, in a taped interview, that my mother told me what had happened that night. To seal the case: my father had economized on extras to his new 1948 Kaiser. There was no car radio.

The foremost lay spokesperson at the time for mental health reform had been unable to rescue her own cousin and could never accept the truth of the matter—that he had been the victim of severe mental illness, a clinical depression ending only in suicide. It’s easy to see why she could never accept the fact and her own underdiagnosis at the time. (Notably, nobody in her three novels of mental illness contemplates suicide.) It wasn’t shame but a latent guilt in thinking she might have done more. Like my mother and siblings, she too was a “suicide survivor,” many of whom bear an inappropriate, lasting sense of guilt.

A few inferences of many that could be made. Literary talent may run in families, but there are no two novels more dissimilar than The Snake Pit and Raintree County. Mental illness may run in families but have a quite different mooring in psychology and life experience, and present in totally different ways, confounding even those with firsthand knowledge of mental illness. It’s safe to say that diagnosis of mental illness remains fraught with uncertainty. And, to the point, this story of the cousins demonstrates how the shame that still attaches in some measure to both mental illness and suicide can override all else.

__________________________________________________________

Excerpted from the Afterword by Larry Lockridge, published in The Snake Pit by Mary Jane Ward. Copyright © 2021 by Library of America. Used by permission of the publisher.

Larry Lockridge

Larry Lockridge is Professor Emeritus of English at New York University, and has held Danforth, Woodrow Wilson, and Guggenheim fellowships. He is the author of several books, including a biography of his father, Shade of the Raintree: The Life and Death of Ross Lockridge, Jr., Author of Raintree County.