“Then a woman with lips blue with cold… whispered in my ear—(we all spoke in whispers there):

‘Could you describe this?’

I said, ‘I can!’”Article continues after advertisement–Anna Akhmatova

*

I’m a writer specializing in very short fiction with a surrealist tinge. Starting in April, as the sirens wailed out my window in locked-down New York, I took to writing fable-like stories, and sending them—as emotional dispatches from a city in trauma—to Motoyuki Shibata, my longtime Japanese translator, in Tokyo. Quickly gathered into a little chapbook, these dispatches seem to have struck a deep chord half way around the world.

As you surely know, New York this spring found itself the world’s epicenter of the coronavirus. And ethnically diverse Jackson Heights, where I live, and the surrounding dense, low-income Queens neighborhoods marked the epicenter’s epicenter. A mere six blocks from me Elmhurst Hospital, whose services I’ve blithely used over the years, became the global image of the city’s unfolding horrors: the rain-sodden crowds outside trying to get tested, the waiting refrigerated morgue trucks, the overwhelmed corridors within. New York went into lockdown late March, and life flipped into a siege of unrelieved, tumultuous dread. Ghostly streets. People suddenly desperately in masks (where did they get them?). Confusing or non-existent local safety guidance, besides the stunning neglect and pathology from the White House. Shortages—of testing, disinfectants, groceries.

And this public trauma revived a personal one. The respiratory nature of the disease brought back my mother’s dying from lung cancer, helplessly gasping for breath as I helplessly looked on. That’s how you died from coronavirus—alone. For several days I had a strange “cold” (was it?) with shortness of breath, chest pain. I spent nights seared rigid with anxiety.

The sirens converged on Elmhurst Hospital round the clock. I read the Facebook post of a friend, an ER doctor in Brooklyn—a short, piercing account of how he propped his cell phone by an elderly woman about to die from the virus, so that her desperately pleading son could gulp out a prayer of farewell to her through his tears, as she lay unconscious. I read this and I sobbed at my laptop.

My twin brother’s father-in-law near Boston succumbed, with his family saying their goodbyes on FaceTime, thanks to the kindness and humanity of his caretaker. I wept again.

It was all too much. The world was ending. In anguish I shut off the news with its infection rates and fatality counts and lack of PPE, shut off Twitter, the catastrophic lies and ravings from the White House.

From this silence, my first story came bursting out. In the streets the magnolias were in blossom; my masked and gloved lockdown walks took me past their luscious pinks and whites, heart and head dark with dread and turmoil. And this grotesque dissonance gave me the sudden, savage inspiration to invert everything—to recast the disease as gilding its victims with the most ravishing beauty the more it ravaged them. (An opposite fate, I noticed later, from Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death.”) “There were beauty contests,” I wrote, “in the ICU’s.” Ugliness became a strutting badge of health. I called the affliction, and the story, “Botticelli.”

New stories came pouring out as almost daily dispatches, eleven more over two weeks, April into May, as the virus raged on and New York’s lockdown was extended.I sent it right away to Moto Shibata in Tokyo—something I often do—telling him I’d written it “for sanity’s sake.” A friend and colleague of Murakami, Moto is probably Japan’s preeminent translator of contemporary American lit. He’s done my books for years, some solely published in Japan. He translated “Botticelli” immediately and read it next day on the radio. He asked for more.

“This is a very strange context we are in now,” he wrote, “and something in addition to literary qualities may make a story work miraculously on readers.”

With this, new stories came pouring out as almost daily dispatches, eleven more over two weeks, April into May, as the virus raged on and New York’s lockdown was extended. I’d written my fiction about traumas before—my parents’ deaths; a shattering romantic breakup—but never mid-experience. I didn’t want to write directly now, factually head on. (That’s not how I write.) I wanted intimate authenticity, but I needed a certain poetic remove—to be fable-like, as with “Botticelli,” for the innocence and darkness, and Kafkaesque haplessness, too, a fable offers. The scale of the pandemic required, for me, a quasi-folkloric sort of voice. “Plague” was the term I used, with its age-old resonance. Never “coronavirus” or “covid.”

My second story featured the ambulances that hurried through the streets, the sight of them at once so fearful and yet poignantly consoling. Some sirens pulsed in an eerie, almost oceanic register, and I imagined the ambulances as whales: great gravely heroic gentle beasts brought in to ferry the sick on their broad backs, red lamps strapped to their heads, until they give out in mortal exhaustion—“nature straining its best to help us reckless, helpless sufferers,” I wrote. I was thinking of nurses and doctors and caretakers as well, surely.

Shopping provoked another dispatch. At one point only a few supermarkets in Jackson Heights were open; even the bodegas were shut. My first anxious venture out to a supermarket, late evening with my girlfriend, turned chaotic, I returned in fever of guilt that I’d gotten us exposed by rashly hurrying us inside. My girlfriend wasn’t ready, she kept protesting, she was the one who did all our shopping, she had her safety routine. She was beside herself. I wrote about finding a little girl on the street overcome with panic and distress—inconsolable because she’s lost her shadow. (There’s an HC Andersen tale about losing one’s shadow, I found out later) I try to reassure her, but I know how dangerous her situation is. And I don’t know how to help her.

I was, I realize, summoning images and correlatives that would set off the release that deep tears bring—for the loss of people and a world, the sadness and fear, the overwhelmed confusion. I was coping with the pandemic, as I could, by weeping over my vision of it constructed with a ballpoint from Staples. I wrote about imploring authorities to stop an unbearable video on TV that keeps showing a simple family picnic, such as once were, no masks, no gloves, plates passed around, cups refilled, a sing-along on shared blanket. I wrote of an old man drowning on our escape route from the infected city, how his humbly attentive ghost troubles my dreams until I have to tell it to leave. (I realize now this came from the passing of my sister-in-law’s father, and my own father’s, too, long ago.) I wrote about bewildering health edicts involving mirrors. About a safe hilltop village where they fly clouds like kites for innocent sport, and gather to gaze down at the dismal quarantined town below. By the end, I was even going for laughs (I’m usually a comic writer) with a disastrous tour of my locked-down writing studio, inspired by the 18th century house-arrest memoir, Voyage Around My Room.

The book I found myself turning to most wasn’t by Camus or Boccaccio or Defoe. It was a 1972 Soviet sci-fi novel by the brothers Arkady and Boris Strugatsky. Roadside Picnic concerns the Zone, a terrifying area of earth where the laws of physics have gone haywire in the debris-strewn aftermath of a visit by aliens. Tarkovsky’s film, Stalker, was loosely drawn from the novel. The Strugatskys wrote the screenplay—removing all the book’s sci-fi, to Tarkovsky’s delight, though retaining a version of the Zone.

Moto Shibata arranged for the stories—which have not yet appeared in English—to be rush-published late May in his translation.Stalker (pronounced “Stullker” by the Strugatskys) is a movie that seems to enrapture people (Geoff Dyer, for example) or bore them stiff (myself). Roadside Picnic with its hardcore sci-fi frights has always been more compelling to me. And I felt we were now living in the novel’s Zone: trapped, and in isolation, in our home neighborhood of Queens. In choking shock at how some malevolent fate had shrunk the worst of the planet’s contagion, forget Wuhan, right to where we were.

I paid homage to Roadside Picnic in a mini-tale of alien artifacts that glisten with unsuspected catastrophic luster, much like the Strugatskys’ sinister alien cobwebs glittering in the dimness of an abandoned Zone garage. I set my version of the Zone in a remote jungle site. My story is actually a prelude, though. A “stalker”-type, a relics’ poacher, goes after those shiny artifacts deep in the heart of the jungle—unaware of the horrors that await him, and the world . That “stalker”-type is me.

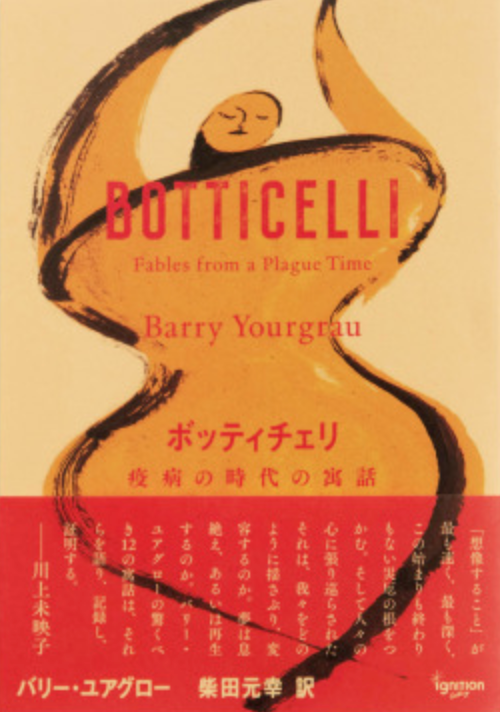

Moto Shibata arranged for the stories—which have not yet appeared in English—to be rush-published late May in his translation. When the mail from Japan worked again, I held in my hand the post-card sized chapbook we’d titled Botticelli: Fables from a Plague Time. Fittingly, the Japanese call ultra-short fiction “palm of the hand” stories. Now the little book with its red blurb band nestles among my assorted facemasks and bottles of Purell, on its front cover a freely-drawn woman who seems in bed but also dancing; on the back, something floating like a Matisse cut-out of a microbe. In between sit the transformations that got me through my suffering—abstract now to me in Japanese. A beautiful, foreign object that’s also my own so-intimate talisman.

Despite the publisher, Ignition Gallery, being an indie arts outfit that eschews Amazon, Botticelli received coverage in all of Japan’s major newspapers and within a month went into a third printing. It’s now in its fourth.

“Imagination,” novelist-of-the-moment Mieko Kawakami (Breasts and Eggs) wrote of the stories, “is the best way to grasp the depths of this disaster seemingly without end.”

“I think for us, these stories were—are—mirrors that beautifully exaggerate what we ourselves have been going through.”I asked Moto why Botticelli resonated with Japanese readers.

“I think for us,” he replied, “these stories were—are—mirrors that beautifully exaggerate what we ourselves have been going through. Our own experience, exquisitely distorted. Magazines and newspapers have published a lot of diary-style accounts of the pandemic, but almost no one had thought of making it into fables. And I realize now,” he added, “I was relying on your stories to come to grips myself with what was unfolding.”

During April and May, Tokyoites dutifully stayed home, Moto noted, and greeted each day with bated breath. “But we weren’t tired yet—we didn’t have the sense we have now.”

The sense things might drag on for many months, even years…

Still. At summer’s close, New York had one of the country’s lowest infection rates, and life has returned to the streets around Elmhurst Hospital.

I hold my breath thinking of what fables the fall might bring.

*

Three Stories from Botticelli

“Botticelli”

The grotesque irony of the disease was how the infected became more and more beautiful, the more the plague ravaged them.

There were beauty contests in the ICU’s. Painters and photographers, poets and balladeers, flocked to the hospital wards to capture and celebrate the loveliness on display in the fever-soaked bedding. The perfections of forms resembled, or perhaps even surpassed, creations from the sublime hand of Botticelli, of Rafaello. Such eyes, such profiles, such grace of sweat-shiny limbs.

The disease was called Botticelli or, by some, Rafaello.

And sometimes, as the artists crowded in, a sudden gasp of horror would be heard, as a painter would all at once realize, from the depth of his or her avid concentration, that those around were now staring at him or her with widened, ravished gazes. And the painter would fumble out the hand mirror everyone carried with them, and groan in wrenching despair at his or her sudden telltale onset of comeliness. The mark of loveliness.

We all were consumed by mirrors, then. In our houses we draped them, and would lift a corner of the cloth to peer, wincing with dread, for the first signs of a finely shaped nose, a creamier or rosier complexion, a more lustrous eye, more luxuriant tresses. Pinker bows of full lips. Nobler brows.

And how we envied those whose plainness and ugliness remained unassailed, perverse badges of their vitality and health. How they would strut about now, smirking, scratching their flabby bellies or their dandruff, stroking their warts, flaunting their flat, bony, sallow cheeks, their crooked chins, their small, dull eyes. They ambled the galleries and museums, the ones that stubbornly hung on open, grunting in triumph and contempt at the centuries of beauty on display.

And so the great reinterpretation began.

“The Whales”

The new leaden stillness spread across the streets. Through the dragging days, the shut-in nights, the stillness was pierced, at first—ominously, wrenchingly—by the wail of ambulances rushing their desperate cargos through the streets to the hospitals.

Then the ambulances broke down or were contaminated and abandoned.

Up from the stillness now, through the windows, rises an eerie oceanic bleating. It’s the whales that have been brought in and put to the ferrying task, being impervious to contagion, it turns out.

If it isn’t rainy, we creep with terrible caution to our roof terrace with a view of the chastened metropolis and its skyscrapers. From there we can watch the great creatures from the ocean deep as they maneuver along below with their majestic tails through the streets newly in leaf, with the red lamps harnessed to their brows pulsing, and their great broad backs bearing the stricken in modified stretchers to the emergency rooms. Their eerie primordial bleating is comforting now, is fearful comfort and a terrible poignancy…nature straining its dumb best to help us reckless, helpless sufferers.

Some days, when we test our courage with an anxious walk to the park, we come upon a prodigious collapsed corpse hauled to the side of the street—dead from exhaustion or from being unable to cope with the change of habitat, so far from deep waters. Young guys would climb up onto the great hulks to pose for triumphant selfies, until the police warned them down.

Many of us have vowed to make a special visit of gratitude to the pens outside the harbor where the whales are brought to from the sea, and housed. But the dangerous days, the weeks, are still too much with us. So we sit by our windows for now, our hearts pierced with fear and a terrible, heartbreaking gratitude, searing as grief, as we hear the bleating and see the great creatures, red-lit, toiling on their errands under the dimming trees as evening returns to the streets.

“Spoon”

First the film production was paused, temporarily. Then the plug was pulled on the whole project.

The film set was abandoned. It had been built with dirt-cheap local labor, so its size was enormous. In fact, in sheer mass, it was the seventh largest city, there deep in the jungle, of the whole country.

When the aliens landed, they settled in the abandoned film-set city for a time. Being deserted, it must have presented a good base to them for their exploratory mission. Or perhaps their mission wasn’t exploratory, exactly, and this was more like a moment in their intergalactic wanderlust when they could pause a while.

At any rate, they were not accustomed to residing in buildings, at least not the ones they found themselves among. So they stayed camped in the streets.

The jungle therefore had little hindrance when it began to encroach on the buildings, and envelope them in ravenous greenery, in lush fibrous vines that covered the structures and bore deep and invasive into the floors, the walls and roofs, the foundations. Heat and humidity did their job too. Soon the engulfed buildings began to rot. Insects flourished and multiplied, stupendously. Particularly a certain kind of mosquito.

The aliens, despise their intergalactic navigations and their hyper-acute technologies, had curiously little immunity against mosquitos. They were helpless. Their spacecraft gleamed, but the ravenous vines had invaded its vital power cells, somehow. They began to perish like, well, like flies. They lay in the streets, gasping fainter and fainter in fright and helplessness until they succumbed.

All of them ended this way. All but one of them.

He took to the river, clinging to logs.

Hundreds of miles away, down the turbid river, he was carried into the ramshackle district hospital where I was working as an accountant. The doctors thought he was an indigenous person of some kind, from one of the tribes, deformed and maddened by malnourishment and a miscellany of chronic jungle ailments. They shoved him away in a back room by himself. And it was in that shabbily tended room where I looked in, idly curious, that he showed me, gasping faintly, a piece of alien metal he had with him. A spoon, to be specific.

The spoon gleamed like treasure from a fairytale.

Before he succumbed—there were mosquitos here, too, it was the bad month for them, the spraying had been careless—he communicated to me the whereabouts of the abandoned film-set city, and the space craft…whose metal, no doubt, gleamed like treasure from a fairy tale.

I quit the hospital. They shrugged at the news; I was an unreliable accountant, given to reading cheap fantasy novels at my untidy desk. I got hold of a boat.

Now I’m on the river, have been for three days. I’ll need one long day more to reach that abandoned film-set city, I calculate, as I crouch by my river bank fire, the spoon gleaming on its oil cloth for my hungry eyes to feast on again. My gun is now starting to rust in the jungle humidity, I notice, despite my oilings. Never mind, it’s a sturdy old gun. I smile, patting it. Yes, a sturdy old gun.

If I could foresee what one long day more brings, I would wish to have known about the scavenging rodents, puny sorts of vermin that came creeping into the enjungled, ruined film set, drawn by the stench of the alien fallen. Whom they fed on, naturally. And then they didn’t slink back into the undergrowth, although some of them died almost immediately from the contagion that had fermented, you might say, in the dead alien flesh. Yes, of course I have my rubberized box of standard medications with me, the pills, sour powders, acrid disinfectants. But the jungle is a vast, tireless laboratory vat of infectious invention. “Standard” is not much use against vermin and their mutant strain of microbes that shimmer like wisps of gleaming silicate, like a haze of tidbits gnawed from gleaming metal ornaments on ruined alien bodies.

If only I could have foreseen what I’m about to learn, I could have turned around and warned the whole world. But alas, that’s not what happens.