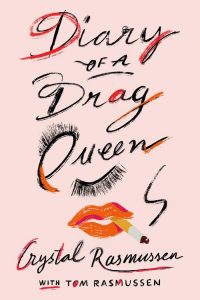

The Secret Language of

Make-Up

Drag Queen Crystal Rasmussen Makes an Icon of Herself

23rd December / le 23 décembre

I’m going out tonight so I spent the better part of the afternoon getting into a full face. Day to day I’ve been wearing less face than usual—a lip stain here, a highlight there—probably because Eve enjoys taking a verbal jab whenever the make-up gets a little cakey, which it does. But it’s the big one tonight before the scene shuts down for Christmas, so I wanted to do full drag-queen-with-a-beard realness. I left myself three and a half hours, and for the first time in my life, I’m ready early.

So I’m sitting, staring at my make-up bag—messy, glitter coated, jangled from four years traveling coast to coast, across the ocean, in and out of makeshift dressing rooms that are actually loos, up and down stairs, in the boot of countless cars. I love my make-up bag.

My make-up bag. The passport that contains a bunch of crèmes, potions, polyfilla, and over-the-counter drugs that diminish the muscles of an overbearing gender binary, allowing me to wrestle it down, even just for a night. These tools are the hardware that allows me to finally live out my childhood fantasies, every one. They’re also margin comments in a history book, connecting me to the radical queens, queers, butch dykes, and trans folk who fought for me to be able to paint my face the way I want to paint it and wear it out in the world.

In my make-up bag are thousands of tricks for me to cover the scars of my teenage acne, or the slice on my chin, from a homophobic attack, that has never quite healed. I love the scars in some ways, but having the devices to cover them allows me to dictate their mark upon me.

In my make-up bag are missing pieces and extra bits—given, received, and shared between my drag sisters and me like heirlooms, like gifts from Christmas crackers. We are reminded of one another whenever we use them. In my make-up bag are hairs cut from the long hair of a drag king friend to make a beard, strewn, unwanted, but so integral to the history this kit holds. In my make-up bag is a kind of self-care that makes you totally healed, a complete person, even if just for a night. In my make-up bag is an ode to the women who gave me a femininity to explore but not to parody (that’s just terrible, lazy drag).

Make-up is, ultimately, about choice, about allowing yourself to choose how the world sees you.

In my make-up bag is jewellery given to me by my friend who was so desperate for me to be kinder to myself that she found things to make me sparkle. And while it’s so easy to talk about colors, powders, primers, highlighters (yum! fave!) with a kind of Zoella level of soullessness, make-up is—to me, to many of us—not an extravagant stockpile of excessive frippery but something that unveils my glory as it veils my face. In a world where power is usually taken from us, make-up lets us draw our battle lines.

Make-up is also a means to writing in a secret language, misunderstood and disregarded by boring dudes who think make-up is “gay,” which allows us to communicate with one another silently or with floods of Facebook messages about Kat Von D’s new matte lipstick. My make-up bag is a kit that allows me to create an illusion that is closer to the truth than the face I was born wearing.

While people question whether wearing make-up is antifeminist (much like they question drag), make-up is, ultimately, about choice, about allowing yourself to choose how the world sees you. The same can be said for not wearing any, especially if you’re expected to by society. People bandy about terms such as fake, but choosing how you want to look is the definition of authentic.

PERFORMANCE MEMO: Amanda Lepore said to me, in a club last night, “Most icons are dead and their image is frozen in time, so I froze mine—blond, red lips, body. Now when you see even this silhouette, you know it’s me. And that’s iconic.”

*

24th December / le 24 décembre

Last night was glorious. We ran in a big bunch and circled the bars and the loos and the dance floor like a murder of spangled crows, ready to pick off anyone who shot us even the faintest hint of a stink eye. After I was dropped off by a few friends who were headed my way, I walked one block alone and instantly felt the real world prickle back into existence.

In a single block I was met with nearly every type of response a drag queen alone on a night-time street seems to invoke. From “Yassss, quaine!” to “Jimmy, check out that fag,” from a popped tongue to a head shaken in disgust, I kept pacing, urged to safety by Crystal, who, through necessity, has become a pro at escaping attacks.

“Keys between the fingers, queen. And if one of them comes close, aim the stiletto heel for the eyeball,” she instructs as my heart near tears through my red-sequinned dress.

A lot of things change when you’re in drag. Of course, the way you feel about yourself changes. Yes, I feel empowered to take up space; I feel momentarily at peace with my gender; I feel emotionally in sync with other femme and non-binary bodies around me and before me; I feel grateful for my forebears. But perhaps, most prominently, I feel scared. Especially when I’m on the street.

The heart of drag, in my experience, is something warm, kind, healing, and vulnerable.

The problem is that when you paint on this barrier, people no longer see you as a person: in drag you’re either sub- or superhuman. By building a new face and transgressing binary lines of gender, you become a visible outlier. People assume many things that they wouldn’t assume about other, plain-clothes folk. And they have the gall to comment on it. People assume we’re all fabulous; we’re all loud; we’re all here for your consumption and entertainment; we’re all here because we aren’t good at other things, because we couldn’t get a real job—yet they expect you to turn a show or a look better than any other person who enters the club.

People assume we’ll take any sexual advance we can get, while also assuming that we’re too freaky to be sexual with—often evidenced by men in cars who kerb-crawl you, then shout at you the moment you tell them to back off. People assume that we’re a little dumb, an accessory, a stunning prop for a brilliant Instagram post. People think we want to go shopping, that we live in hovels underground (although, to be fair, given the economics of performance work, most of the queens I know do), and that we’re self-involved—bitchy, even.

Sure, the face of drag is resilience and strength. The face of drag is funny. The face of drag is powerful. It’s critical and catty and mean and often problematic. But the heart of drag, in my experience, is something warm, kind, healing, and vulnerable.

I arrived home, make-up peeling off from one-block’s worth of adrenalized sweat. I raced up the stairs of my Lower East Side sublet, terrified I’d meet an attacker in the stairwell. Keys, door, lights on. Check every single cupboard and cranny for potential attackers. Crystal has had many hits out against her, and that paranoia often creeps into my reality.

“When you’ve had eight high-profile divorces and have been through the witness protection program seven times, you know to check the cupboards first, darling.”

Text the others to tell them I’m home safe, and they all text back. Going out in drag is great, but getting back unscathed is even better.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Diary of a Drag Queen by Crystal Rasmussen with Tom Rasmussen. Published by FSG Originals, Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2019, 2020 by Tom Rasmussen. All rights reserved.

Crystal Rasmussen and Tom Rasmussen

Crystal Rasmussen is a global superstar in her mind and a regular columnist at Refinery29. Look up the term "Global Phenomenon" and you will find a picture of Crystal's face. Living in overdraft since the Wall Street Crash of 1929, Crystal forms one fifth of DENIM, the drag supergroup, and is adored for her lazy demeanor and her powerful falsetto.

Tom Rasmussen is a journalist and queer performer. When not in drag, they are a regular contributor at The Independent, Dazed, i-D, LOVE, and Refinery29. Their work has also been featured in The Guardian, Vice, Broadly, Tank, and Gay Times, and they were named an LGBT trailblazer by The Dots and one of the voices of now for i-D. Tom also forms half of the radical queer punk band ACM, and is coauthor of Diary of a Drag Queen.