The Sandwich That Helped Feed Puerto Rico After FEMA Failed

Chef José Andrés on Getting to Work in the Aftermath of Maria

A military meal that is “ready-to-eat” is something no human being is ever ready to eat. Stuck on a battlefield, far from home or any kind of kitchen, an MRE (meal, ready to eat) may be a lifesaver. But it is not a meal as anyone would understand it. The contents of a brown plastic MRE bag are so heavily processed and preserved that they only have a distant relationship with food.

Today’s MRE is the latest industrialized solution to a problem the United States has tried to solve since the Revolutionary War: how to provide regular rations to the troops. In the Civil War, those rations were salt pork and a rock-solid bread known for good reason as “hardtack.” For most of American combat history after that, the answer was canned food. But starting in the 1970s, the military began experimenting with something lighter. At first, it was freeze-dried food, developed by an Iraqi-American food scientist. By the early 1990s, the experimental techniques evolved into something more like packed and flavored mush, in more than a dozen varieties, or what the military prefer to call “menus.”

If you peel back the seal on its heavy plastic cover, you immediately realize that the MRE is designed like other weaponry. It must survive impossible conditions like extremes of heat and cold. It must survive immersion in floodwater and the parched air of the desert. It must contain enough preservatives and packaging to last at least three years at 80 degrees, but even longer if the conditions are cooler. Why the need to last three years? Because the Pentagon needs to stockpile meals around the world in case of combat.

Inside you’ll find some plastic-wrapped crackers and cookies. Maybe a plastic packet of nuts and raisins, and a powdered drink mix that needs water to make it liquid. The main course is a glutinous sludge that looks like it’s been scraped off a sidewalk, while its ingredients sound like the contents of a laboratory. An official mark on the pouch must be some kind of joke: Inspected for Wholesomeness by U.S. Department of Agriculture.

This “wholesome” packet of calories (on average, 1,250 kilocalories) is skewed toward fat (36 percent) and carbohydrates (51 percent). Sadly for civilians and military personnel, it’s also low on fiber, which means that people get constipated after eating the MREs for a few days. This may help on the battlefield, where there are good reasons to slow down the need to take a shit. But if you’re not facing live bullets every day, you may not appreciate the constipation. For young people, this is hard to deal with, but imagine what it’s like for the elderly. There’s a reason why people joke that MRE stands for Meals Refusing to Exit or Massive Rectal Expulsion. Even for those on the battlefield, the MRE is only supposed to be eaten for 21 days.

As the Pentagon puts it, the MRE has some well-defined purposes and requirements. “The Meal, Ready-To-Eat (MRE) is designed to sustain an individual in heavy activity such as military training or during actual military operations when normal food service facilities are not available,” says the Defense Logistics Agency.

How do you eat an MRE? Whichever way you want. You can eat it cold, or boil the whole bag in water (if you have water and can heat it). If you can’t do either, there’s something called “a flameless ration heating device” packed into each bag that warms up the contents in ten minutes using water, which triggers chemical reactions.

They say that an army marches on its stomach, and that may be true. But a marching army also needs to carry its own food, and that helps define an MRE: its weight and dimensions are limited by the need to fit inside “military field clothing pockets.” In reality, on a typical 72-hour mission, packing nine MREs is too bulky, so the servicemen and -women find ways to rip out what they truly need and throw away the rest.

When all else fails, an MRE is better than going hungry. For civilians, including after Hurricane Katrina, it is certainly better than nothing. But it is no way to feed people for any extended period. I could see this firsthand in Haiti on that day when I saw children playing soccer with an MRE. If people living in desperate poverty cannot see these bags as food, who can?

In Puerto Rico, apart from the meals World Central Kitchen prepared, those plastic military bags of calories were the only food delivered in any reasonable quantities. MREs were the competition, and they were an expensive and soulless one at that. At current Pentagon prices, a box of 12 MREs costs $119, which is $9.91 per plastic bag of calories, not including the cost of shipping to the island and distribution across the island.

Our food was sourced locally to save money and help revive the local economy. Those boxes of MREs came from small towns and big cities in South Carolina, Florida and Ohio. An MRE is a matter of survival. A freshly cooked plate of local food is a meal you’re sharing with your family and community. I like to say that a hot meal is more than just food; it’s a plate of hope. An MRE is almost hopeless. When you serve a plate of food, you gather intelligence about who needs feeding. When you dump a pile of MREs, you learn nothing about the true nature of the crisis.

“When all else fails, an MRE is better than going hungry. . . But it is no way to feed people for any extended period. I could see this firsthand in Haiti on that day when I saw children playing soccer with an MRE. If people living in desperate poverty cannot see these bags as food, who can?”

Yet FEMA was determined to rely on MREs because it didn’t want to rely on the Chefs For Puerto Rico, and no other nonprofit or contractor could produce the food. The alternative was handing out bags of chips and candy, or bags of uncooked rice and beans. At least the chips didn’t need clean water and power before you could eat them. We were locked into a daily comparison between our chicken and rice, and a packet of chemicals that could be reconstituted to give the impression of chicken and rice. Only a government machine and the industrialized food economy could think that endless MREs were the way to feed millions of Americans for weeks on end. We had identified the enemy, and the enemy was an MRE.

*

Our solution to the challenge of creating a meal that was easy to transport and stayed edible for long periods was a simple, old-school idea: the ham and cheese sandwich. I have created many avant-garde dishes as a chef but there are few meals I’m prouder of than the hundreds of thousands of sandwiches we made in Puerto Rico.

Our sandwich line started out in the main dining room of José Enrique’s restaurant, where we developed our methods, building on what we started in the Reef restaurant in Houston. Now at the arena, we could spread out into two huge sandwich lines. These lines were made up of young children and retirees, first responders after a long day’s work and charity volunteers from the mainland, as well as many homeless hurricane victims who preferred to spend the day helping others rather than sitting inside a shelter. There were also off-duty members of the coast guard and officers from Homeland Security Investigations. They all became experts in making my ideal sandwich.

We sourced the white sliced bread in vast quantities from local bakeries, and bought equally huge quantities of ham and cheese slices from José Santiago and Sam’s Club. But the key ingredient was the mayonnaise. Lots and lots and lots of mayonnaise, mixed with tomato ketchup for some extra flavor, and sometimes mustard too. At side stations, volunteers prepared huge bowls of mayo-ketchup mix, and cut the ham and cheese slices out of packets for quick assembly. Along two main lines of tables, other volunteers laid out slices of bread. Others set about dolloping mayo on each one, followed by a slice of cheese, a slice of ham and another generous slop of mayo. This masterpiece was finished off with a top slice of bread.

At the heart of this factory was my sergeant-major of sandwiches: a heroic volunteer called Dilka Benitez. Dilka was a wheelchair basketball player who helped organize the island’s wheelchair ballers. Those organizational skills were clear in the sandwich factory, where she kept a close control of the volunteers, veering from encouragement to discipline in a few yells. She carefully managed the numbers and supplies, from the ham and cheese to the finished sandwiches. Dilka was helped greatly by two professionals: David Strong, my director of strategic initiatives at ThinkFoodGroup, and chef Griselle Vila, who runs her own catering company on the island. Together they built the volunteers into a hugely successful and productive team that changed every hour, as the volunteers switched in and out.

The sandwich line was one of my first stops when I returned to Puerto Rico after a few days of recovery back home in Washington. I walked into the darkened chamber of the Coliseum where dozens of volunteers at rows of tables were dolloping mayonnaise and slapping ham and cheese onto endless slices of white bread. Olé Olé Olé Olé, Olé Olé, we sang together like the victorious fans inside a soccer stadium, as we just heard the news that we’d hit a huge target: 20,000 delicious—and portable—ham and cheese sandwiches made in just one day.

“People of America! People of the world,” I said to the volunteers and to all those watching what would become another video on social media. “You see the people of Puerto Rico feeding the people of Puerto Rico. Today, 20,000 sandwiches. You see Puerto Rico together. The men of Puerto Rico and the women of Puerto Rico coming together. You should always be very proud of this moment. The first lady, she’s my hero. She gave us the opportunity to use this space. I think the governor has been doing a great job. But more important, this is not about politics. This is about you, you, you, you, and you. One day, 20 years from now, you will be able to tell the story of how you together fed every man, woman and every child a happy plate of food. Thank you. Thank you. We love you. But I see we are not putting enough mayo.”

As the cavernous room filled with cheers, laughter and applause, I turned to consult with my team: the paper bags we were using were sucking the moisture out of the sandwiches. We needed another solution to transport the sandwiches; one that wouldn’t dry out the food as it sat in storage or traveled across the hot island all day. I suggested wrapping each one in a square of parchment paper.

“We don’t want to just give food,” I told my team as more boxes of sandwiches were carried to the door. “We want to give the best food. And please put more mayo.”

I walked down the cinder-block hallway into the steaming kitchen, where a team of chefs were sweating next to giant vats of chicken and rice. My attitude was all about the protein. The trays of food needed more chicken, just like the paella pans outside. We couldn’t short-change the hungry people of Puerto Rico. They needed the calories and they expected more chicken.

“We need to give people more food than we usually do,” I explained. “I think it’s important. I’m always questioning because people are hungry.”

“Our solution to the challenge of creating a meal that was easy to transport and stayed edible for long periods was a simple, old-school idea: the ham and cheese sandwich. I have created many avant-garde dishes as a chef but there are few meals I’m prouder of than the hundreds of thousands of sandwiches we made in Puerto Rico.”

While I was back home, we had grown impressively. We created a pop-up kitchen in Guaynabo, west of San Juan, and served 5000 people with chicken and rice. In a matter of days we went from 20,000 meals a day to 40,000 to now 60,000. We smashed through the milestone of 200,000 total meals, and were going to crush 300,000 on the day I returned. Our culinary school kitchens were going to open across the island in a matter of days, and I knew our daily meal numbers would spike again.

However, all our activity at the arena was now an unexpected and unwanted source of friction with its managers. We moved into El Choli with the support of the island’s first lady, on a mission to feed the hungry. We thought, perhaps naively, that this publicly-funded space was a giant donation-in-kind. It wasn’t. After a week of cooking, the management company SMG gave us an ultimatum, out of the blue: pay $10,000 a day to cover the costs of staffing and power, or leave in 24 hours. I was astonished. We were trapped, in a crisis, as we were trying to achieve the impossible. SMG wanted to back-date the bill to our first day there, saying they were a private company that did not get FEMA funding. The assumption seemed to be that we were awash with FEMA cash but the truth was that we were burning all our cash on food. We negotiated the cost down to $8000 a day, but I was upset. My feelings about the arena were reinforced a few days later when the managers blocked us from expanding into more kitchen space. Domino’s Pizza offered to open up its ovens to help our operation, using their own arena cooks. But SMG said they weren’t allowed to, under the terms of their contract. The ovens stayed cold while the Domino’s cooks joined our sandwich line. It made no sense to me, even though I know that arenas are complicated places with costs of their own.

The arena team was now boosted by more chefs, including several from my ThinkFoodGroup. Jennifer Herrera was a personal chef based in Dorado Beach who had grown up and trained in New York. Her mother was from Ponce, and she paid special attention to our satellite kitchen there. “It was a very personal experience,” she said, “being able to cook arroz con gandules, carne frita and a substantial warm meal to warm their stomachs and warm their hearts.”

Our hero was a 25-year-old whose dedication and drive was an inspiration to us all. Alejandro Perez was executive chef at the Happy Crab restaurant in Dorado when he was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma. He finished his treatment a month before Maria and was warned not to go back to work. His doctors said any strain or accident could kill him immediately. His response: “It will be worth it. One life for 15,000 or 20,000 people I feed? It’s worth it.”

Initially Perez wanted to open a community kitchen in his home area of Bayamon, but the municipality said they couldn’t support it. So he joined Chefs For Puerto Rico and came to El Choli to work long hours cooking thousands of meals. “My family thought it was risky and then they were concerned because I was doing crazy hours,” he said. “Emotionally I felt useless to my family, to my wife. Especially my wife Carla. She left school because she had to pay for my treatment. It took a toll on me. But since we started here, she supported me all the way. She said she didn’t care it has no pay. I just need to get out to do what I want. She even went with me to make sure I wasn’t doing anything too crazy. She said, ‘Go and do it. You are passionate about this.’ “I wish I could do this forever. I have never seen so many chefs, so many different people, work so well together, with one purpose, for one idea.”

What inspired Alejandro to do all this? Meeting people on the island in worse situations. “I met this lady in Rincón whose house was gone,” he recalled. “It was just a wooden frame. She was living behind a wall. She stayed in her bathroom through the hurricane as her house was getting ripped apart. But she was a community leader and she was helping everyone else. She was the one who needed help the most, but she was helping others. What we do here isn’t one third of what has to be done. There are people sacrificing themselves. We’re just giving our time and our skills. When I think things are going bad, I just go through my phone and look at photos like that. It’s a reminder that it doesn’t matter what goes on inside the kitchen. It’s all for the greater good.”

Erin organized a doctor to get him a checkup and the news was amazing: he was in full remission. When Alejandro returned to El Choli, everyone stood outside cheering, holding signs to celebrate his spirit and good health. It looked like another miracle.

Everywhere my team traveled, there were signs of distress, two and a half weeks after the hurricane. In Humacao, at the eastern edge of the island where Maria first made landfall, a simple sign by the road said it all: La playa tiene hambre. The beach is hungry.

While the island was still hungry, I drove over to the convention center for another mass care meeting. Our contract with FEMA was signed a day earlier, and would run for just two more days. But we had more than fulfilled our end of the deal. Since October 4th, when the contract began, we had prepared and delivered more than 190,000 meals. By the time it was over, we would hit more than 300,000 on a contract that would only pay us for 140,000. The money wasn’t the most pressing issue for us; the hunger bothered us much, much more. We didn’t care about total numbers. We only cared about fulfilling all the orders we received.

It was my first time back at the FEMA headquarters since they kicked me out of the building at gunpoint. There was still an endless flow of volunteers from charities, newly arrived from the airport. Unlike the newcomers, who are issued credentials in no time, I still had no official ID card to enter the building, two weeks after the start of Chefs For Puerto Rico. Nobody ever told me why: it seemed petty and personal but that’s how FEMA wanted to behave. So I was forced to grab people as they walked into the secure space—or rather, officials walked up to me to ask me what was going on outside their Caribbean green zone. Eventually FEMA official Elizabeth DiPaolo came down the escalator to talk to me outside the security line.

“I can feed 500,000 people tomorrow,” I told her. “But I need to know what you think is the real need. We can use local kitchens and local food to get money into the local economy. I have already activated so many kitchens. I just need to understand how these contracts are going to work.”

“The first contract with you is no problem,” she said patiently. “That contract is already done. But we can’t make another contract like that. That contract was just to get you started.”

“But the requests we get are endless,” I said.

“We know we need to do at least two million meals a day,” she readily conceded. “But the people in charge are the state of Puerto Rico. We are all partners in support of them. In fact, we have to do six million meals a day. Work with us as a partner.”

“Let me loose,” I begged. “I can feed the island.”

“The first contract was easy but if you want a second, it’s something else. You’ve met your requirements already.”

“It’s the people of Puerto Rico who want food. And I can’t provide it to them.”

“So do you want another contract?” she asked, once again coming back to the bureaucratic needs, not the needs of the people.

“I don’t need another contract. I already have people on the radio saying I’m getting rich from the people of Puerto Rico.”

“Who is saying that?” Elizabeth asked, incredulous.

“The number one radio station on the island,” I told her, knowing she had no idea what that was or where to find it. “You should hear what they say about FEMA and the governor too.”

“Can you really do that many meals?” she asked, sounding just as incredulous as she did about the radio station.

“I have 11 kitchens already and can find more. There’s a catering company at the airport and they can do more than 250,000. And I can do it cheaper and faster than anyone else. And on time.”

The mass care meeting was about to begin, so we walked across the street to a huge windowless meeting room in the Sheraton hotel. Elizabeth opened the meeting by asking people to tell everyone their accomplishments for the day, hopefully with numbers, their plans for tomorrow and any challenges they might face to get there.

The Puerto Rico State Guard reported delivering 4.3 million bottles of water and 2 million meals, since the hurricane landed. The military was clearly the biggest operation on the island, and all of those meals were MREs.

The Department of Education reported they provided 115,000 meals to date through the first lady’s “stop and go” distribution points across the island, including 2050 meals that day. With the island’s schools reopening tomorrow, there was a chance they could cook for many more. But the process of reopening and activating school kitchens was slow, and the education officials said it was taking time to get the orders through to the regional directors of the schools in the mountains.

Puerto Rican agriculture officials said they were still struggling to get enough truck drivers to move produce and water around. Their contractor had one hundred trucks but they were looking to activate many more. To me, it wasn’t clear why the military couldn’t or wouldn’t help. Perhaps they were simply in the dark, but the Pentagon is never short of trucks or drivers. And the need was urgent: the next day the island’s Department of the Family was expecting to receive one million pounds of food from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

At that point, the meeting turned to the nonprofits, or what they call volunteer agencies. FEMA mostly wanted to make sure we were all cooperating, or “playing in a big sandbox together,” as they put it. But it wasn’t clear what purpose or goals the group had, never mind how anyone could cooperate.

For now, the meeting was given over to the strange characters that disasters seem to attract. A new group had just flown in from Florida: Mutual Aid Disaster Relief, a fringe group with anarchist leanings that emerged after Katrina. Then the Scientologists said they had 60 pallets of goods coming from New York, and wondered how they could get them to Puerto Rico.

“FEMA doesn’t ship donations,” said one official. “We don’t take the task of bringing donations over.”

The Scientologists asked for help and the group pitched in with random ideas. FedEx perhaps? How about DHL? Maybe the airlines like JetBlue could help? Or they could get sponsored by a big corporation?

“We have the funds but we just don’t have the actual transportation,” the Scientologists replied.

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. It was not just totally detached from the crisis on the island. It was even detached from my experiences of solving problems on the island.

It was the turn of the American Red Cross to weigh in, as the organization whose unique charter gives it a congressional mandate to deliver disaster relief, coordinated by FEMA. The Red Cross report was a window into how inadequate the disaster relief was on the island. They said they had distributed 1.2 million pounds of food to date, which sounded like a lot until you divided it between 3.4 million Puerto Ricans needing 3 meals a day for the last 20 days. It was less than an ounce of daily food for each Puerto Rican.

Even the measures of food were confusing and FEMA had no way of understanding what was going on. The Red Cross talked about pounds of food, while others were talking about pallets. We preferred to talk about meals, which was actually what FEMA’s contracts specified. All these counts went into a big Excel spreadsheet that FEMA maintained and emailed every day. At the bottom of the spreadsheet, the total count of food was supposed to be there for everyone to see. Instead, the count was a calculating error because there was no standard unit of food that everyone used. If FEMA couldn’t manage a spreadsheet, how could it manage an emergency?

“As part of our distribution efforts we are doing some feeding activity with prepared foods,” the Red Cross explained. “Water continues to be a challenge and we’re also distributing water filters, things like that. It depends on the solution of how we can get clean water to small communities and homes. We need to know what are the communities, and the needs and the long-term strategies because some areas will be without for a long time. We’re trying to get creative right now. A lot of the normal tools in the toolbox are not there right now.”

“The Red Cross report was a window into how inadequate the disaster relief was on the island. They said they had distributed 1.2 million pounds of food to date, which sounded like a lot until you divided it between 3.4 million Puerto Ricans needing 3 meals a day for the last 20 days. It was less than an ounce of daily food for each Puerto Rican.”

So there was no water pretty much everywhere, and they had no idea what the solution would be or when it would come. The Red Cross did say it had handed out some water filters for “almost 3,000” families. I couldn’t understand why nobody was screaming about a water crisis for American citizens. Where was the sense of urgency?

The Red Cross was supplying a little food, they said. But the reality was, as they admitted, a bit more like people surviving on their own. “People are able to cook in a lot of communities,” they reported. “There are a lot of grills and propane users. We’re trying to support that effort as much as we can because we know there’s delays in getting food distribution.”

This is what we all knew from driving around the island, and what you had to assume in the absence of food riots. People were relying on their home supplies of food and propane. But who knew how long that would last? It was all very random and disorganized. And if you knew people were cooking like this, why would you continue to supply so many MREs?

The reality is that around 40 percent of Puerto Ricans qualify for what we used to call food stamps. On the island, this is called nutritional assistance but it is paid electronically on cards. Just 20 percent of the assistance can be redeemed as cash to pay for food, which is all of $80 for a family of four. With the lack of power and communications on the island, the supermarkets were finding it impossible to swipe cards, including the food assistance cards.

Why weren’t the Red Cross and FEMA moving from the card system to good old-fashioned cash? Because the Trump administration was unwilling to rethink the basics of the system in this crisis. When the island’s Department of the Family asked to increase the amount that could be drawn as cash from 20 to 50 percent, the Trump USDA said no. As a consolation, it said people could use the cards to buy hot food or sandwiches in approved stores. If you walked into a Puerto Rican supermarket, with empty shelves and refrigerators with no power, you would know how unrealistic that was. Even the Trump agriculture officials knew how bad the situation was. “We understand that at this

point in time all food retail outlets in Puerto Rico are challenged by a lack of inventory, power and connectivity issues,” the USDA wrote. “Additionally, ATMs are experiencing connectivity issues and limits on cash.”

As an exercise in mass care, the meeting was just that: an exercise. It was as disconnected from the reality of food shortages in Puerto Rico as the sushi bar downstairs in the gleaming white bar of the Sheraton hotel.

The Salvation Army, with all its resources, was typical. They said they had heard of areas of need, but didn’t have the people available to assess those needs. In any case, their feeding numbers were in the single thousands. In Ponce, one of their largest sites, they were feeding a couple thousand people a day.

“20,000?” asked someone hopefully.

“No. 2 to 3000,” the Salvation Army replied.

It was finally my turn to talk. “So we have our famous chef José Andrés,” said Elizabeth. “Do you want to report on what you guys are doing today?”

I told them we were already distributing to 16 municipalities, with four kitchens operational across the island, and preparations to expand quickly, including in Manatí in the north and Fajardo to the east. We were even feeding federal employees. “Today the National Guard called us in Toa Baja and they said they didn’t have hot meals for the last two weeks, so we sent them 400 meals of rice and chicken. Even though they kicked me out of this building,” I told the gathering, which included military representatives. “The best partnership we have in the last two weeks, God bless them all, is HSI from Homeland Security. Many of them are border patrol and many of them are Puerto Rican. They have 40 trucks, and they go to the rough and hard areas. They told me they wished they could bring food and water. These guys are very quick and they work on their own. Every day we’ve given them 5000 sandwiches to deliver. Every day. We have a fairly good track on where the need is because of them: which houses need help. So HSI has been great.

“If we can activate a helicopter operation, everyone wants to reach the middle of the island, but I already identified the people who can prepare 20,000 hot meals precisely to deliver through army helicopters. It sounds so crazy but I only need to get to the army to say: Can you do that? The meals are prepared here by Puerto Ricans. People can receive 3500-calorie meals anywhere that we want to land the helicopters. These are hot meals without having to open kitchens. At least this can be helpful for the next week or two until we are able to open roads in many areas. If anyone is interested in this, I have the intelligence on this and we could do 100,000 meals delivered by helicopter in 24 hours.”

I told them about my maps, created by the army team, with all its details about resources. “This isn’t just a dead map. This is a live map,” I explained. “I’m dreaming we are coming to this map, put the numbers here, and everything will pop up here and we’ll know immediately how many people we are feeding in every part of this island. So we can see the potential customers, people who are hungry, versus the potential of the givers, all of us. And we try to match the givers with the receivers. The army is doing a great job but I feel this could be a great map just to simplify our lives and look to see who we are, where we are, how we support each other and how we are feeding everybody in the areas that need it.”

“we were already distributing to 16 municipalities, with four kitchens operational across the island, and preparations to expand quickly, including in Manatí in the north and Fajardo to the east. We were even feeding federal employees.”

Another FEMA official talked about a different kind of exercise: last week he asked everyone to put sticky notes on a map to track what everybody was doing. Almost three weeks after the hurricane, the federal government was using sticky notes to manage information. The year was 2017, and everybody had access to Google Maps and Forms on their smartphones. But FEMA wanted people to stick paper on a map.

The main recipients of this information, FEMA made clear, was not the people feeding the hungry but their bosses, who wanted only the simplest of data. “We want to show it to leadership and say, ‘These are the numbers you want to see.’ They don’t want to see a long report, they want to see a quick snapshot of what’s going on,” the FEMA official said. It wasn’t clear what leadership he was talking about, but we all knew that President Trump didn’t read his briefings and preferred pictures to words.

“The leadership wants to see quick and dirty,” Elizabeth explained. “The need is 2.2 million meals on the island. Right now, we’re doing 200,000. Our deficit is 1.8 million or—I can’t do math. We are 1.8 million meals short. So that’s why we need to get the urgency. This isn’t going away. We’re doing this much today and this much tomorrow. But this has got to be sustained over several months. So we really have to think longer term.”

In fact, FEMA put the daily need at 6 million meals—3 meals for each of the 2.2 million people needing food relief. Of that 200,000 meals a day, my operation was already producing one-third. The other nonprofits were paralyzed or making only token efforts at providing food and water.

The remaining meals were almost entirely MREs from the military, but even those numbers fell far short of what was needed. According to the Pentagon, the military had delivered 7.7 million meals and 6.3 million liters of water since the hurricane, almost three weeks earlier. Neither of those numbers was anything like enough for an island of 3.4 million people, most of whom had no clean water, no money to buy food, no supermarkets to shop in and no power to cook a meal.

“Chef, thank you,” said one of the Scientologists, who started applauding. It was kind of him, but I found the meeting as depressing as anything else I’d seen in the disaster zone.

“You’re the only one doing these numbers,” Elizabeth told me afterward. “The only one out there.”

That evening, Trump tweeted a video of federal efforts in Puerto Rico, saying, “Nobody could have done what I’ve done for #PuertoRico with so little appreciation. So much work!” The video began with a swipe at the media: “What the fake news media won’t show you in Puerto Rico . . .” There were military helicopters lifting concrete slabs to shore up what looked like the Guajataca Dam, which was close to failing. There was the coast guard delivering medicine to the island of Culebra. But mostly the videos were a badly spliced together collection of unnamed agencies delivering bottles of water in unidentified places that looked like Puerto Rico. Perhaps they couldn’t cite the numbers for food and water delivered because they didn’t have a “quick and dirty” view, or because the spreadsheet counts were all calculating errors. The video ended, naturally, with Trump himself in Puerto Rico, including at his paper towel–throwing session, set to heroic music. Because the video was for one person, not for the American citizens of Puerto Rico.

I couldn’t help but reply. “You’ve done nothing Sir,” I tweeted. “The people at @fema @USNavy @USArmy @DHSgov @National-Guard are Americans in action! To lead you must be a follower . . .”

I returned to the AC Hotel, where my team of chefs from El Choli and our satellite operations was meeting at the end of a long day. My experience at FEMA made me feel we were out there on our own, in terms of our vision for feeding the hungry.

“We can feed the island,” I told them. “We don’t need anybody else. Everybody says we need the partners, but you don’t need the partners. They should just leave it to the professionals. We can teach people how to do this themselves.”

“The video ended, naturally, with Trump himself in Puerto Rico, including at his paper towel–throwing session, set to heroic music. Because the video was for one person, not for the American citizens of Puerto Rico.”

Karla had just come back from a trip to Manatí in the north and Mayagüez on the western coast, and her report was not good. We were exploring how to set up a satellite operation at the culinary school, but the supplies were not getting through.

“Oh my God,” she said. “It’s really, really bad. No communication at all. They can’t even get products for their kitchens there. Can we at least do sandwiches for them? The only supplier that normally goes there is José Santiago, delivering on Wednesdays and Fridays. They only have a small walk-in freezer. But they have three grills, one oven and a lot of big pans we can use.

“We took sandwiches for the Salvation Army there. When we got to them, the Salvation Army said, ‘Thank God. We were just going to Manatí. We don’t have any food.’ They need a lot of help. We passed one house and I could see the closet from the street because half of the house was gone. We tried to get to one part of town, but the road was flooded. They didn’t have hot food or anything. Maybe we could do paellas there? I was sobbing in the car. They are really struggling.”

I explained to the team my solution for scaling up even more: an airline catering company I had met, called Sky Caterers. They could produce 300,000 meals a day with sandwiches, fresh fruit and chips. They could also make hot meals with chicken and fish, or vegetarian meals. Each meal would be packaged as it is on a plane. We could start delivering to the military whenever they wanted. And the meals would be produced in Puerto Rico by Puerto Ricans, helping the local economy along the way.

As for our sandwiches, I needed the team to maintain quality. “Increase the quantity of mayo,” I said, yet again. “The paper bag is sucking them dry. That was a bad idea. We created the best sandwich in hunger relief, but this is drying out the sandwiches. Older people love the sandwiches but without a lot of water, it’s hard for them to chew. They need to stay moist. Aluminum pans is how we began delivering them. It’s so cool because they bring the pans back to you. If you put paper between the layers, they stay moist. I want people to say this is the first hunger relief operation where the food was good. Nobody at FEMA or in the NGOs talks about how good the food is. They only talk about how much food did we give away.”

Our tensions with FEMA were worse than a difference of emphasis or values. Erin Schrode told the group how a FEMA official had come over the day before. “He wanted to check that all our volunteers were really our volunteers, because they weren’t getting as many volunteers as they would like,” she said. “They thought we might be getting them over here.”

What he was really checking was how on earth we could produce so many great sandwiches. After he asked about our volunteers, he stayed for an hour making sandwiches himself.

__________________________________

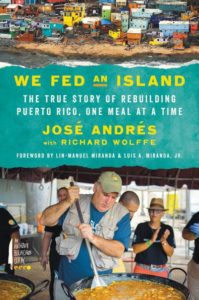

From We Fed An Island: The True Story of Rebuilding Puerto Rico, One Meal At A Time. Courtesy of Anthony Bourdain/Ecco. Copyright © 2018 by José Andrés with Richard Wolffe.

José Andrés and Richard Wolffe

José Andrés is the founder and chairman of World Central Kitchen, the NGO behind #ChefsForPuertoRico, and co-founder of ThinkFoodGroup, which has more than 30 restaurants around the world. Andrés is a Michelin-starred, James Beard-winning chef, and was named among Time’s “100 Most Influential People.” He is also the author of two cookbooks. His book, We Fed An Island, is available from Anthony Bourdain/Ecco.

Richard Wolffe is the co-writer of Andrés’ cookbooks and his two PBS series on regional cooking in Spain. Formerly at the Financial Times, Newsweek, and NBC News, Wolffe is a columnist for The Guardian and the New York Times-bestselling author of three books about Barack Obama.