The Sandwich That Helped Feed Puerto Rico After FEMA Failed

Chef José Andrés on Getting to Work in the Aftermath of Maria

The Salvation Army, with all its resources, was typical. They said they had heard of areas of need, but didn’t have the people available to assess those needs. In any case, their feeding numbers were in the single thousands. In Ponce, one of their largest sites, they were feeding a couple thousand people a day.

“20,000?” asked someone hopefully.

“No. 2 to 3000,” the Salvation Army replied.

It was finally my turn to talk. “So we have our famous chef José Andrés,” said Elizabeth. “Do you want to report on what you guys are doing today?”

I told them we were already distributing to 16 municipalities, with four kitchens operational across the island, and preparations to expand quickly, including in Manatí in the north and Fajardo to the east. We were even feeding federal employees. “Today the National Guard called us in Toa Baja and they said they didn’t have hot meals for the last two weeks, so we sent them 400 meals of rice and chicken. Even though they kicked me out of this building,” I told the gathering, which included military representatives. “The best partnership we have in the last two weeks, God bless them all, is HSI from Homeland Security. Many of them are border patrol and many of them are Puerto Rican. They have 40 trucks, and they go to the rough and hard areas. They told me they wished they could bring food and water. These guys are very quick and they work on their own. Every day we’ve given them 5000 sandwiches to deliver. Every day. We have a fairly good track on where the need is because of them: which houses need help. So HSI has been great.

“If we can activate a helicopter operation, everyone wants to reach the middle of the island, but I already identified the people who can prepare 20,000 hot meals precisely to deliver through army helicopters. It sounds so crazy but I only need to get to the army to say: Can you do that? The meals are prepared here by Puerto Ricans. People can receive 3500-calorie meals anywhere that we want to land the helicopters. These are hot meals without having to open kitchens. At least this can be helpful for the next week or two until we are able to open roads in many areas. If anyone is interested in this, I have the intelligence on this and we could do 100,000 meals delivered by helicopter in 24 hours.”

I told them about my maps, created by the army team, with all its details about resources. “This isn’t just a dead map. This is a live map,” I explained. “I’m dreaming we are coming to this map, put the numbers here, and everything will pop up here and we’ll know immediately how many people we are feeding in every part of this island. So we can see the potential customers, people who are hungry, versus the potential of the givers, all of us. And we try to match the givers with the receivers. The army is doing a great job but I feel this could be a great map just to simplify our lives and look to see who we are, where we are, how we support each other and how we are feeding everybody in the areas that need it.”

“we were already distributing to 16 municipalities, with four kitchens operational across the island, and preparations to expand quickly, including in Manatí in the north and Fajardo to the east. We were even feeding federal employees.”Another FEMA official talked about a different kind of exercise: last week he asked everyone to put sticky notes on a map to track what everybody was doing. Almost three weeks after the hurricane, the federal government was using sticky notes to manage information. The year was 2017, and everybody had access to Google Maps and Forms on their smartphones. But FEMA wanted people to stick paper on a map.

The main recipients of this information, FEMA made clear, was not the people feeding the hungry but their bosses, who wanted only the simplest of data. “We want to show it to leadership and say, ‘These are the numbers you want to see.’ They don’t want to see a long report, they want to see a quick snapshot of what’s going on,” the FEMA official said. It wasn’t clear what leadership he was talking about, but we all knew that President Trump didn’t read his briefings and preferred pictures to words.

“The leadership wants to see quick and dirty,” Elizabeth explained. “The need is 2.2 million meals on the island. Right now, we’re doing 200,000. Our deficit is 1.8 million or—I can’t do math. We are 1.8 million meals short. So that’s why we need to get the urgency. This isn’t going away. We’re doing this much today and this much tomorrow. But this has got to be sustained over several months. So we really have to think longer term.”

In fact, FEMA put the daily need at 6 million meals—3 meals for each of the 2.2 million people needing food relief. Of that 200,000 meals a day, my operation was already producing one-third. The other nonprofits were paralyzed or making only token efforts at providing food and water.

The remaining meals were almost entirely MREs from the military, but even those numbers fell far short of what was needed. According to the Pentagon, the military had delivered 7.7 million meals and 6.3 million liters of water since the hurricane, almost three weeks earlier. Neither of those numbers was anything like enough for an island of 3.4 million people, most of whom had no clean water, no money to buy food, no supermarkets to shop in and no power to cook a meal.

“Chef, thank you,” said one of the Scientologists, who started applauding. It was kind of him, but I found the meeting as depressing as anything else I’d seen in the disaster zone.

“You’re the only one doing these numbers,” Elizabeth told me afterward. “The only one out there.”

That evening, Trump tweeted a video of federal efforts in Puerto Rico, saying, “Nobody could have done what I’ve done for #PuertoRico with so little appreciation. So much work!” The video began with a swipe at the media: “What the fake news media won’t show you in Puerto Rico . . .” There were military helicopters lifting concrete slabs to shore up what looked like the Guajataca Dam, which was close to failing. There was the coast guard delivering medicine to the island of Culebra. But mostly the videos were a badly spliced together collection of unnamed agencies delivering bottles of water in unidentified places that looked like Puerto Rico. Perhaps they couldn’t cite the numbers for food and water delivered because they didn’t have a “quick and dirty” view, or because the spreadsheet counts were all calculating errors. The video ended, naturally, with Trump himself in Puerto Rico, including at his paper towel–throwing session, set to heroic music. Because the video was for one person, not for the American citizens of Puerto Rico.

I couldn’t help but reply. “You’ve done nothing Sir,” I tweeted. “The people at @fema @USNavy @USArmy @DHSgov @National-Guard are Americans in action! To lead you must be a follower . . .”

I returned to the AC Hotel, where my team of chefs from El Choli and our satellite operations was meeting at the end of a long day. My experience at FEMA made me feel we were out there on our own, in terms of our vision for feeding the hungry.

“We can feed the island,” I told them. “We don’t need anybody else. Everybody says we need the partners, but you don’t need the partners. They should just leave it to the professionals. We can teach people how to do this themselves.”

“The video ended, naturally, with Trump himself in Puerto Rico, including at his paper towel–throwing session, set to heroic music. Because the video was for one person, not for the American citizens of Puerto Rico.”Karla had just come back from a trip to Manatí in the north and Mayagüez on the western coast, and her report was not good. We were exploring how to set up a satellite operation at the culinary school, but the supplies were not getting through.

“Oh my God,” she said. “It’s really, really bad. No communication at all. They can’t even get products for their kitchens there. Can we at least do sandwiches for them? The only supplier that normally goes there is José Santiago, delivering on Wednesdays and Fridays. They only have a small walk-in freezer. But they have three grills, one oven and a lot of big pans we can use.

“We took sandwiches for the Salvation Army there. When we got to them, the Salvation Army said, ‘Thank God. We were just going to Manatí. We don’t have any food.’ They need a lot of help. We passed one house and I could see the closet from the street because half of the house was gone. We tried to get to one part of town, but the road was flooded. They didn’t have hot food or anything. Maybe we could do paellas there? I was sobbing in the car. They are really struggling.”

I explained to the team my solution for scaling up even more: an airline catering company I had met, called Sky Caterers. They could produce 300,000 meals a day with sandwiches, fresh fruit and chips. They could also make hot meals with chicken and fish, or vegetarian meals. Each meal would be packaged as it is on a plane. We could start delivering to the military whenever they wanted. And the meals would be produced in Puerto Rico by Puerto Ricans, helping the local economy along the way.

As for our sandwiches, I needed the team to maintain quality. “Increase the quantity of mayo,” I said, yet again. “The paper bag is sucking them dry. That was a bad idea. We created the best sandwich in hunger relief, but this is drying out the sandwiches. Older people love the sandwiches but without a lot of water, it’s hard for them to chew. They need to stay moist. Aluminum pans is how we began delivering them. It’s so cool because they bring the pans back to you. If you put paper between the layers, they stay moist. I want people to say this is the first hunger relief operation where the food was good. Nobody at FEMA or in the NGOs talks about how good the food is. They only talk about how much food did we give away.”

Our tensions with FEMA were worse than a difference of emphasis or values. Erin Schrode told the group how a FEMA official had come over the day before. “He wanted to check that all our volunteers were really our volunteers, because they weren’t getting as many volunteers as they would like,” she said. “They thought we might be getting them over here.”

What he was really checking was how on earth we could produce so many great sandwiches. After he asked about our volunteers, he stayed for an hour making sandwiches himself.

__________________________________

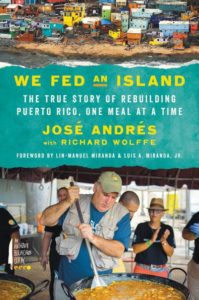

From We Fed An Island: The True Story of Rebuilding Puerto Rico, One Meal At A Time. Courtesy of Anthony Bourdain/Ecco. Copyright © 2018 by José Andrés with Richard Wolffe.