Last week I received a postcard from Italy. At first I thought it was a mistake. The message was short but very personal. The sender’s father had “died peacefully” at a care facility in Seoul. The postcard was signed in black ink with a name I didn’t immediately recognize. But later on the memory came back. An evening I had spent with Soyeon several years ago in Florence. She had told me about her father then, and the things he had done.

Days passed and I forgot about it. Then one evening, I was sitting by the pool, watching a helicopter circle the canyon. My wife appeared with a tray of drinks.

“Are the girls back from school?”

“Volleyball and band,” she said. “I thought we might have a cocktail before they get home.”

On the tray next to the glasses was the postcard from Italy. My wife pointed at it by nodding her head. “Who is Soyeon? Someone you met in Europe?”

“One of Teddy’s friends.”

“From Florence? Man or woman?”

“Woman.”

“Why would she want you to know her father was dead? Did you meet him when you were there?”

“No, she told me about him.”

My wife made herself comfortable on a lounge chair and drank slowly. She was wearing the red platform espadrilles I had bought her in the Florence duty-free.

I had only been there for an afternoon and a night. Enough time to visit a few churches, I’d thought, get the smell of incense in my clothes, stand before a few paintings and statues, the Annunciation or Birth of Venus. Teddy, my wife’s friend who resided there full-time, would be in Brooklyn meeting his new gallerist, which meant I could use his apartment.

I didn’t know anything about Florence itself—but had seen some illustrations in a history book on my wife’s desk. There must have been other pictures, but I only remember the executions. Stacks of flaming wood with the body of a heretic tied up on a pole. Another showed platforms constructed for some drawn-out form of public torture.

Teddy was an American painter who had purposely moved to an Italian city where modern art was not possible, and so he felt no pressure when making it. His apartment was in the center of town. He had described in an email the ancient front door with blunt spikes embedded in the wood, a small stand nearby for food and newspapers—even a Florentine barber, with brushed steel chairs and bottles of green aftershave in the window. The apartment took up the second floor in a fifteenth-century building above a Chanel boutique that was once a medieval stable. Purses and bags now hung in place of bridles.

The keys had been left with one of the girls in the shop. When I arrived in the early afternoon, there was a line of tourists waiting to go in. I talked to the guard and he asked me to wait inside the door. Soyeon was with a customer, but eventually finished her sale and came over with the key. The barrel was long and uncomplicated. A smooth, rusted brown. There was a key chain with it. A red patent leather heart. Soyeon’s nails were red too. When she smiled, I noticed a few of her teeth were crooked.

“I didn’t know anything about Florence itself—but had seen some illustrations in a history book on my wife’s desk. There must have been other pictures, but I only remember the executions.”

She was finishing early that night and wanted to walk me up to Piazzale Michelangelo. To really experience Florence, she told me, you had to leave the city altogether. I had never enjoyed grand views or sunsets, preferring the small beauty of a leaf, or the strangeness of a puddle. But before I could think of an excuse, she had moved silently back across the carpet, toward a wall of jeweled purses, where there were people waiting. She had straight black hair and white skin with freckles around her nose. Soyeon’s clothes were tight on her body. She wore black heels with a pearl on each toe.

Teddy’s apartment had stone floors and the walls were cold to the touch. The ceilings were fifteen feet high. Cobwebs fringed wooden beams. Over the centuries people had died and been born within a few feet of where I was standing. The two main rooms were taken up by enormous squares of canvas on dark wood easels. The rooms smelled of linseed oil and the paintings were hung with sheets, as though signifying death in the absence of their creator.

I took a cold shower, then went outside. The markets were bustling with people. I stopped to buy tin cases of chocolate almonds for my daughters, and stood listening at the edge of tour groups. Some shops sold lace collars, and I bought three. They came flat, folded in pink tissue.

Before returning to the apartment, I picked up half a loaf of bread and some tomatoes wrapped in newspaper. The apartment was dark now with the shutters closed. It felt quiet after my long walk, and I wanted to sleep again. I removed my shoes and socks and let my feet cool on the stone tiles. Then I went into the kitchen and ran cold water from the faucet into my cupped hands. After a few mouthfuls, I ate the bread and tomatoes with some black pepper on the patio. The furniture out there was plastic and faded. A few of the chairs were on their backs. One had a broken leg. I imagined drunken laughter as bodies sprawled. There were a few empty bottles, and ashtrays with floating cigarette ends.

After the food and cold water I was content to sit and read. But then I remembered Soyeon, so I brushed my teeth quickly and went outside. The shop was closed but the lights were still on. Soyeon was waiting by the door. She had changed into other clothes and was wearing plain, flat shoes. She had pulled her hair back into a ponytail and would have looked like a student, if not for a silk Chanel scarf tied around her neck.

When we started walking, my legs felt tired and I wanted to give up and find a restaurant. It was going to be a long march in the evening heat with a steep climb. But I felt powerless to stop what was now happening, as though it would have taken more energy not to go along with Soyeon’s plan.

After crossing the Arno River, she began to ask questions. How did I meet my wife. How old were my two daughters. Did I have any pets. I answered in a friendly way, but was too tired to give details.

Then she started talking. First about the shop. Working for Chanel. Her boss from Rome. Dressing the mannequins. A Christmas card every year from Karl Lagerfeld. Then she told me about her mother and growing up in Korea. The crowd on the street had thinned by this time, and we could stroll side by side, like people who had known each other for a long time and had real things to say.

She came from a suburb of Seoul, a place I couldn’t imagine. Their home was a two-room apartment that overlooked a main highway. The kitchen was full of plants. Some of the plants grew leaves you could eat. She told me there were tower blocks all around, and Laundromats—and that from her window you could see the edge of a golf course.

“It was going to be a long march in the evening heat with a steep climb. But I felt powerless to stop what was now happening, as though it would have taken more energy not to go along with Soyeon’s plan.”

Her mother was eighteen when Soyeon was conceived. She was a small woman who cleaned offices, and in the evening watched soap operas on the couch with her feet tucked neatly under her body. Orphaned through war when she was three, her heart had long searched for a place to drop anchor.

Soyeon’s father was much older. A businessman. A golfer. He often worked late and wore a gray suit with thin white stripes. Out of all the people in the office building, hundreds of workers, he had chosen her, Soyeon’s mother.

At first it was just looks. Then a few words of greeting. After that, he unscrewed her cleaning bottles to put flowers in. Left notes with the opposite weather forecast to make her laugh. She saved his cubicle for last, making him work even later if he wanted to see her. Emptying his trash can of papers and tea cans was something Soyeon’s mother looked forward to. She was young then, and wanted to keep everything her businessman had ever touched.

If no one was around, his hand sometimes touched hers. She felt her body waking from a long, impenetrable slumber. This romance went on privately for a good while because the businessman lived outside Seoul in a house with his wife, teenage daughters, and a gray kitten.

Soyeon’s mother knew from soap operas that happiness often comes at a price; that once lives are tangled up, they can never be untangled. Pain is proof of something worthwhile.

Then one day he appeared at her door. It was dark out. His tie had been loosened. She wanted him to come inside.

When it was over they held hands, listening to voices from the television. The blinds were open and they could see all the lights of the city.

By the time Soyeon was born, her mother had left the office complex and was cleaning in a small factory. There was more dirt, but also more money. She missed seeing her businessman, but other workers had realized there was something going on.

He was not there for Soyeon’s actual birth, but paid for a new apartment in the same building. It was another very small home. Only big enough for two. But at night they could hear each other being tossed around by dreams.

Soyeon met her father for the first time when she was three. He came to their house and ate noodles with imitation crab. After, he sat on the couch and looked at Soyeon. He asked questions but all she wanted was to play. She attended kindergarten then, in a tower block near the factory where her mother was employed.

Soyeon remembers how much she liked her father. But their laughter led only to the sadness of being apart.

One day, they all went to the zoo. Soyeon ran from cage to cage. Her parents walked behind holding hands. Soyeon thought it was the beginning of something, but it was the end.

A week later, her mother came to get her from school with a bruise on her face. Her lip had swollen so it was easier to nod when the teachers asked if she was okay. Soyeon rubbed her mother’s feet. Brought her green tea. Watered the plants and wiped the windows. Soyeon’s father did not visit for many months. During this time her mother sometimes put on perfume and slipped away when Soyeon was in bed. Later there would be talking and muffled laughter. A man’s voice, but not her father’s.

During the winter it happened again. He was waiting for her in a parking lot, his body shaking with jealousy and rage. Soyeon’s mother told everyone she slipped on ice. A cracked rib kept her awake. Shallowed her breathing. One eye seemed like it might never open again.

The boss of the factory called her into his office. He gave her coffee from a machine. It was just plain coffee in those days that came through a nozzle into a brown cup. His hair was already gray and the staff called him “grandfather” behind his back. The boss listened to her story, then went into another room to call his wife. She told him to let the girl and her daughter live at the factory for a week. Maybe the abuser would think they had run away and give up trying to find them.

Above the factory floor was an elevated glass office where the boss liked to watch operations and entertain visitors. The lights were always on, and you reached it by metal staircase. At the very back of the factory was a row of big rooms. Some of the rooms had purple carpet and filing cabinets, while others contained enormous cupboards with spare toilet paper and cleaning supplies. The biggest room had beds and a shower. It was for technicians who came from China to fix the machines. Sometimes it took many days if a part was ordered. The technicians weren’t supposed to smoke in the room. They joked with the factory staff, and showed pictures of their families.

Soyeon’s mother was given the day off and told to return in the evening with a bag of things they would need to stay. An elaborate plan of coming and going was worked out so the other workers wouldn’t know she was sleeping in the apartment for Chinese technicians. Each day, she would take Soyeon to day care early, then sit in the park until it was safe to arrive at work at the normal time.

In the evening, she would collect her daughter, then, after a walk and for something to eat, would return to the factory after eight. Soyeon remembered the wooden sign outside day care with children’s faces drawn on it. She had thought one of the faces was hers. But it was everybody and at the same time not a single person.

*

As we neared the top of Piazzale Michelangelo, sunlight filled the streets like gold fabric.

The part Soyeon said she remembered most was being allowed to ride her tricycle up and down the factory floor. It was quiet with the machines down. She felt good there. She remembers the smoothness of the floor. How easy it was to build up speed. The smell of cardboard and oil in one corridor. Hot plastic in another. The factory made toys. It was really a dream come true, Soyeon told me, except the room they slept in smelled like cigarettes.

Near the small cafeteria with its chilled cabinets of salad and cans of green tea, there was an unlocked room where all the broken toys went. Soyeon wanted to explore that room more than anything, and although her mother had forbidden it— after a week in the factory she got her chance, because Soyeon’s father had found out where they were.

It was the middle of the night, but he was outside screaming and rattling the doors of the main entrance.

Soyeon’s mother jumped out of bed and ran with her daughter to the room of defective toys. The toys were in giant boxes. They would bury themselves in broken dolls until he went away. Soyeon was lifted into one. Then her mother got in. The smell of plastic was very strong. Soyeon wanted to play but was supposed to keep her hands still.

“One day, they all went to the zoo. Soyeon ran from cage to cage. Her parents walked behind holding hands. Soyeon thought it was the beginning of something, but it was the end.”

After a while their heads popped out and they listened. Soyeon said she remembered it now like a scary cartoon. The shouting had stopped. No more rattling of the doors. Just to be certain, they stayed a bit longer, went through the toys one by one to pass the time, inspecting each doll, trying to figure out what had gone wrong and why they were in there.

When it got late they found the cafeteria and shared green tea mousse. Soyeon’s mother stacked coins in place of the container. The food made them cheerful, so they walked around the factory holding hands, and singing songs they knew from television. Then suddenly he was standing in front of them. His gray suit was ripped and his shirttail hung out like a white tongue. He rushed forward and grabbed Soyeon’s mother’s wrists.

“Go to the toy room!” she screamed to her daughter.

But Soyeon hid behind a machine, watching as her mother broke free, then ran up the metal staircase to the raised office. Soyeon’s father chased after her, as though it were a game they were playing, as though everything that was happening had been decided upon long before.

Once inside the glass room, Soyeon’s mother locked the door, while her father said her name over and over. Then he stopped speaking and pulled savagely on the handle. Then he tried kicking the door but it wouldn’t open. Soyeon’s mother was like a fish in a bowl. Then he pounded on the door and both his hands went through as the glass shattered. As he unlocked it from inside, Soyeon’s mother ran backward into a corner, raising her arms to protect herself. But instead of hitting her, the businessman went calmly to an office chair and sat down before a computer, as though he were at work.

Without knowing why, Soyeon said she left her hiding place and went up the metal stairs to the glass office. She knew there was an orange metal box with a red cross on it. She had seen it before. They had the same one at her school. It was full of medicine and white ribbon. When Soyeon got to the top of the stairs, the office was very bright, and there was glass on the floor.

Her mother was slumped over, sobbing. Then she saw her daughter standing there. “Go play,” she said weakly.

Sitting in the office chair bleeding was Soyeon’s father. The man who’d held her mother’s hand at the zoo. Who had fed Soyeon imitation crab as she played on the carpet. There was also blood on his cheeks and on the white collar of his shirt. But mostly it dripped to the floor and onto his black shoes.

Soyeon got the orange box and took the lid off. She did not feel afraid. She took out two rolls of bandage and went to her father. She could see his eyes clearly. The expression in them made her feel good. Soyeon took the bandage and went round and round. Her only concern was to get it straight. She had wrapped dolls before, but this man was not a doll. At first the blood came through in dots like eyes watching. Then the bandage stayed white. Soyeon’s mother stood up and was looking. Her father could not use his hands for anything, so kept them in the air like he was surprised at everything that had happened in the toy factory.

By this point Soyeon and I had reached the summit, a tiny square bustling with tourists and souvenir stands. The sun had almost completely sunk. It was no longer shimmering in the river, nor golden in the streets.

Soyeon said she never saw her father again after that night. But nineteen years later her mother called her apartment in Florence to say he had collapsed at his workplace. The cleaning lady found him lying on the carpet by his desk. He was alive, but unable to talk or move one side of his body.

Over the next several years, Soyeon’s mother visited him at the rehabilitation hospital. She had not seen her businessman for almost two decades, but admitted there had been letters exchanged.

At first she went to the hospital once every two weeks. Then once per week, then twice. She read romance books to him aloud. Touched his hands and rubbed his arms, trying to arouse feeling in the parts of his body where there was nothing. She told him stories about their daughter in Europe, and showed pictures of her growing up. His other family didn’t visit much. But if she was caught, Soyeon’s mother planned to say she was his best school friend’s younger sister.

Soyeon said she was sure her mother would meet the other family one day, but it never happened.

After visiting, she got home in time for her soap operas. So much had taken place since she’d begun following each show—so many ruined lives redeemed.

Sometimes she took all the postcards her daughter had sent from Italy and laid them out on the table beside his hospital bed. The nurses said he could see and he could hear. Soyeon’s mother had even sent her a photograph of them together at the hospital. It was in a frame beside her bed where she could look at it.

On the steps down, Soyeon took my arm for balance and asked if it wasn’t the saddest case of true love I had ever heard?

That was how she saw it.

When we got back to town, the streets were packed with tourists strolling after dinner. Some parents had let their children run ahead to the souvenir shops. The cafés were full of people talking and drinking from tiny cups.

Soyeon didn’t live in the center of Florence and had to take a bus home. I waited with her at the stop. When we saw lights, she asked if I would like to see where she lived.

*

On my long walk back to Teddy’s apartment, I imagined her face at the bus window. The silence when she got home. She would put her bag down, pull off her shoes, and go soundlessly through the place where she lived, completely alone, but all around—the voices and faces of memory, hovering like unquenched fires.

I pictured us together on the steps at dusk.

The feeling when she touched my arm.

The moon about to rise.

The wrapping of her father’s hands in white ribbon.

*

In the morning I locked the keys inside the apartment as I was instructed. Then I went to the Museo Ferragamo on Piazza Santa Trinità. There were paintings from his home, and photographs of Salvatore as a young designer. One wall was a display of wooden shoe lasts, with names written on the wood: Audrey Hepburn, Ingrid Bergman, the Duchess of Windsor. . .

In a dark corner at the back of the museum was a projection of some classic Hollywood film. Young women in sequined dresses and red lipstick. One of the actors was Marilyn Monroe. She had white hair and perfect eyebrows.

Soyeon had said her mother was beautiful as a teenage girl.

That was why her father had fallen for her.

That was how she had caught the attention of such an important businessman in the office building where she cleaned.

My wife picked up the postcard and read aloud the part Soyeon had written about her father dying peacefully, at the care facility in Korea. I hadn’t thought so before, but now we both agreed, it was the saddest case of true love we had ever heard.

__________________________________

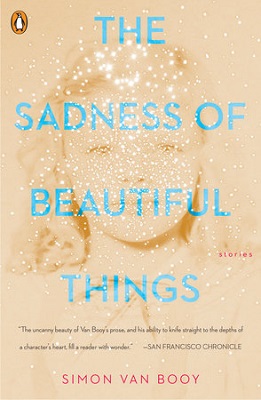

From The Sadness Of Beautiful Things. Used with permission of Penguin Books. Copyright © 2018 by Simon Van Booy.