The Real Story Behind the Creation

of the Atomic Bomb

Demystifying Robert Oppenheimer

The second act of Dr. Atomic, a 2005 opera by American composer John Adams, captures the long moments in 1945 just before the Trinity Test; J. Robert Oppenheimer, who led the Manhattan Project, waits for the weather to pass and the early morning skies to clear so that all gathered in the New Mexico desert might witness the first explosion of the atomic bomb. The pause and countdown that precedes the momentous event is filtered through Oppenheimer’s eyes as he nervously considers the other scientists, politicians, citizens, and circumstances that he organized and deployed in the name of Science, Duty and American patriotism. While Oppenheimer is central to the opera, it does not give him the final proclamation, or even direct ownership of the bomb; rather, the opera ends with a dying Japanese woman politely, repeatedly, asking for water.

The opera’s shift away from Oppenheimer at the work’s final moment of judgement is just one of many examples of the ways a variety of artists and writers have attempted to grapple with Oppenheimer’s legacy.

2018 saw a resurgence of portrayals of Oppenheimer: not only was the official audio of Dr. Atomic released, but Robert Redford also announced he would be adapting the nonfiction book 109 East Palace by Jennet Conant into a feature-length movie. The year also included two fictional works: Trinity by Louisa Hall and my own Y: Oppenheimer, Horseman of Los Alamos. So why this sudden spike in interest?

From my perspective as novelist and poet, the multiple narratives of J. Robert Oppenheimer are fascinating: he was a Jewish man raised by German emigrants to become the lead of the weapons project that helped to end WWII; he was a polymath who could speak multiple languages, including Latin and Sanskrit, and adored the poetry of John Donne and George Herbert; he was a communist-turned-patriot who tangled himself into a love triangle with Dr. Jean Tatlock and his wife Kitty during the extreme heat of his directorship of the Manhattan Project, an affair that would eventually become exposed during the hearings in the early 1950s and lead to the stripping of his security clearance. I don’t necessarily admire the man, but I do understand his importance in our contemporary moment. His story is dramatic and slices through many of the myths of mid-20th century America.

Louisa Hall, Trinity

Louisa Hall, Trinity

This novel works through the problems of Oppenheimer in a wide-ranging set of examinations, at times poetic and startling, at other times historical and heavy in rhetoric. Constructed as a set of vignettes, each chapter tells the story of Oppenheimer from a character peripheral to the scientist. It is this basic structure that asks the reader to consider the ramifications that a man like Oppenheimer has on those around him; his profound, and often subtle, gravity can still be felt pulling decades later, even for those who are multiple degrees apart from him. These narratives are structured as testimonials, as the characters named at the start of each chapter recount their of the time spent orbiting around Oppenheimer. As such, they mix the personal details of the teller with the legends told and retold about the famous scientist.

Lydia Millet, Oh Pure and Radiant Heart

Lydia Millet, Oh Pure and Radiant Heart

Different than Hall’s naturalistic narratives, this fantastical novel literally brings Oppenheimer into the contemporary moment a resurrected trio of famous scientists navigate the ethical questions that have developed in the wake of their legacy. Alongside Leo Szilard and Enrico Fermi, Oppenheimer is mysteriously resurrected in a reversal of the obliterating flash, made manifest in a startling flash, and slowly adopted as part of the Second Coming. All the while, the protagonist, Ann, guides the three through their messianic reappearance and its surreal ending.

Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, American Prometheus

Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin, American Prometheus

This is the Pulitzer Prize-winning definitive biography of J. Robert Oppenheimer that is rich in detail and massive in scope. For readers craving a factual, while entertaining, exploration of the scientist’s entire life, including the stripping of his Top Secret clearance post-WWII and subsequent life in the Caribbean, this book is the absolute best.

Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb

Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb

A wide-ranging, dense history of the Manhattan Project, this tome also won the Pulitzer Prize and is widely considered the best book on the subject. Oppenheimer plays a central role in the middle portions of the book, as the director at Los Alamos, and is perfect those readers wanting to better understand the scale of the scientist’s work as it fits into the larger context of the creation of the atomic bomb.

Ed. by Alice Kimball Smith and Charles Weiner, Robert Oppenheimer: Letters and Recollections

Ed. by Alice Kimball Smith and Charles Weiner, Robert Oppenheimer: Letters and Recollections

This collection of letters, mostly from his youth and time before his directorship of the Manhattan Project, give insight into the tender and captivating character at the core of the scientist. While American Prometheus and other biographies of Oppenheimer, quote liberally from this book, it is well worth reading it on its own to better track the of his thinking as a young man and the various nodes of influence that impacted him.

Jennet Conant, 109 East Palace: Robert Oppenheimer and the Secret City of Los Alamos

Jennet Conant, 109 East Palace: Robert Oppenheimer and the Secret City of Los Alamos

This book is an intimate recounting of the Manhattan Project and Los Alamos, primarily through Dorthy McKibbin, the woman responsible for settling the scientists when they first arrived in Santa Fe before they left for Los Alamos. A close confidant of the scientist, the exploration of McKibbin’s biography alongside that of Oppenheimer’s, and their intertwined histories, grants this book unique insight into the magnetic pull that New Mexico had on both of them. It is reportedly in the process of being made into a major motion picture.

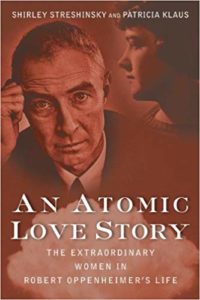

Shirley Streshinsky and Patricia Klaus, An Atomic Love Story

Shirley Streshinsky and Patricia Klaus, An Atomic Love Story

This book focuses on the history of the women in Oppenheimer’s life, detailing the lives of his wife Kitty, his mistress Jean Tatlock and his lover Ruth Sherman Tolman. A companion in spirit to Hall’s novel, this book undertakes the task of recounting those closest to Oppenheimer and his relationships with each of them. It more than makes the argument that each of the three women were accomplished, brilliant people who deserve to have their own narratives highlighted.

Aaron Tucker

Aaron Tucker is the author of two collections of poetry, irresponsible mediums: the chesspoems of Marcel Duchamp and punchlines, as well as the two scholarly manuscripts Virtual Weaponry: The Militarized Internet in Popular Cinema and Interfacing with the Internet in Popular Cinema. His current collaborative project, Loss Sets, translates poems into sculptures which are then 3D printed; he is also the co-creator of The Chessbard, an app that transforms chess games into poems. In addition, he is a lecturer in the English department at Ryerson University.