The Question Haunting the Hungarian People: “What Would You Have Done?”

Rory MacLean Travels to the Forgotten Parts of Europe

I knew the road of old, running south out of the Carpathians onto the Great Hungarian Plain. The mountains fell away behind me as the sun warmed the valleys ahead. Oaks and hornbeams clung to the slopes. Smoky hazelnut trees pirouetted in the breeze. Carpets of green inwrought with snow and flecked with lilac-cupped crocuses spread across the meadows. A river of viridescent verges, the Tisza, meandered through the fields, its oxbows glittering like twists of silver. I drank in the early spring as if it were an elixir, giving me life and revitalizing my spirit. Already my return to Hungary felt like a homecoming, although in ways I hadn’t begun to imagine.

“Na, Kind,” said Alajos, grasping me in his carpenter’s arms. “Du bist zu Hause.”

Kid, you are home.

Thirty years ago he had welcomed me to Tokaj with the same embrace, wearing leis of dried paprika. He and his wife Panni had flung strings of garlic around my neck like garlands of flowers. Great sacks of cabbages, boxes of oranges and bags of sweet peppers, their skins as translucent as the skins of Klimt’s women, had been stacked around the house. At the time of my first visit their son Sandor had just opened a grocery shop next door. I knew of Panni’s death but the shop?

“Gone,” replied Alajos, gesturing towards town. “Now we have Aldi.”

He stroked his white bristles with the stubs of his fingers, the tips severed long ago by a power saw, and limped ahead, ushering me through the coiling vines to the front door. He had aged of course, growing more stooped and grey, the skin under his eyes crosshatched with wrinkles, but inside the house was still as colorful as a painter’s palette: red plaid curtains, blue twined carpets, a tablecloth edged in lace and embroidered with yellow blossoms. After Panni’s passing, their three daughters—Lara, Lili and Szonja—had moved in to care for Alajos. Now they fussed him into a chair, scolded him for going out without his cane and brought us a dusty bottle of Crimean champagne, bought three decades before and set aside for the day of my return.

“I’ve worked up quite a thirst waiting for you to come back,” he said, wrestling with the cork, lacking the strength to dislodge it. Without a word, Lara eased the bottle out of his hands and opened it. As she poured our glasses, he said, with playful pessimism, “The alcohol will help me to forget that life is worse than yesterday . . .”

“. . . but better than tomorrow?” I teased.

He lifted his glass. A ribbon of the national colors—green, white and red—was still stitched into his lapel but I noticed that the psoriasis had spread over his hands. He was over 90 now and I treasured him as friend, exemplar and a key source of stories in my first book.

“Remember what I told you: Hungary placed its faith in the losers of every war since the 16th century. This 21st century will be no exception.” Alajos said in toast: “To a once hopeful Hungary. Long may we mourn her death.”

Unlike him, the ancient champagne hadn’t aged well.

“Our history is complicated,” Alajos had once said to me, no more prone to exaggeration than any of his countrymen. The Magyars, a Mongol tribe, had first stormed across the steppes and into the embrace of the Carpathians around ad 895. Their fierce horsemen then raided deep into the west, ravaging Germany and Italy, playing their part in burying classical civilization in the Dark Ages. Their enemies prayed, “A sagittis Hungarorum libera nos domine”—deliver us from the arrows of the Hungarians—and God answered by defeating them at the Battle of Lechfeld.

The vanquished tribe settled on the Central Plain, abandoned their nomadic habits and organized themselves into a state. In time that state fell under Habsburg rule, and later molded itself into Austro-Hungary. At the start of the 20th century Budapest was home to a dozen future Nobel Prize winners, the filmmaker who would create Casablanca and the physicists who would help to spark the Manhattan Project and nuclear age.

But the Great War ended its heyday, reducing the kingdom to a quarter of its original size. In the hope of regaining its land, its embittered leaders forged an alliance with Nazi Germany, contributing 250,000 soldiers to its assault on Russia. When the tide turned against Hitler, Budapest tried to make peace with the Allies. In response, German troops occupied the country, installed a puppet government under the fascist Arrow Cross Party and set about executing or deporting more than half a million Jews. Another 280,000 Hungarians were raped, murdered or deported when the country fell to the Red Army. Next, a quarter of a million ethnic Germans were expelled and ten Soviet-style labor camps built within its borders, to save the trouble of transporting political prisoners to the USSR. Some 200,000 more Hungarians fled the country during and after the 1956 revolution. When the Wall fell and Hungary then joined the EU, Alajos (and I) had thought that the nightmare was over at last.

I told him of the changes that I had seen on my journey, of hopes betrayed, fears manipulated and people choosing to believe lies rather than face difficult questions.

Late into the night I read aloud parts of my first book, recounting the stories that he had once told me, closing a circle. His eyesight had deteriorated over the years and in any case he didn’t speak English so I translated his words back into German, leaning close to the lamp, watching expressions pass across his dear face. “After the war I went back to school as a mature student,” I read out, quoting Alajos back to himself. “One day—during Latin class—a man appeared at the classroom door and asked for me by name. I stood up. He showed me his identification card—he was ÁVH, state security—and he ordered, “Follow me.” What could I do?

I followed. We walked to the police station. He showed me to an empty room. “Wait here,” he said and left me for two hours. Then a man I’d never seen before came into the room.

“Stand up!” barked Alajos, taking up his story again, recalling the new policeman’s order. He lifted himself to his feet and said, “The man asked me if I’d ever been to the West and I told him I’d been a prisoner in Belgium in the war and for that he slapped me hard across the face.”

Alajos snapped back his head as if he’d been hit again, as if the pain still stung across the years.

“Then he told me that I could go and from that moment I was a collaborator, as most of us were. I was frightened and fear made me cooperate. I had a wife and children. I didn’t want to die. I wanted them to live. They gave half of my house to the policeman. I was permitted to occupy the remaining part, for which I was obliged to pay rent. My tormentor slept in my old bedroom.” Alajos paused and asked me, as he had done 30 years before, “What would you have done?”

Thirty years on I still ponder that question, repeating it to myself again and again. Thirty years ago, in that same bedroom, I’d slept between cotton wedding sheets long stored in scented drawers, dreaming of lying in a bowl of potpourri, and waking into a time of hope after so much tragedy.

Now I woke to whispers, to the rustle of clothing and the muffled clink of crockery. Around Alajos in the next room whirled his three daughters and an indeterminate number of grandchildren, slipping in and out of the kitchen, balancing plates of smoked salami and buttered breakfast kifli bread rolls. I sat up in bed and watched the careful preparations by the half-light of the closed shutters, moved beyond words. My sudden laughter startled the family, sparking their own in turn. Alajos fixed his almond eyes on me and declared with mock severity: “You can live a quiet life—drink my wine, go to bed and die early. Or you can get up and learn something.”

Suddenly everyone was talking, tempo and volume turned up as if by a switch. Bacon, eggs and potato pancakes sizzled in a pan.

A kettle whistled on the cooker. Four children pulled me from bed to table, giggling, trying out their German.

“Hallo hallo.”

“How are you?”

“Mein Name ist Maria.”

Coffee was poured and a dressing gown draped around my shoulders.

“Thank you,” I said as a fifth child placed a cinnamon pastry in my hand.

“Nichts zu danken,” said Alajos, welcoming me back into the heart of the family: modest, loving, without condition or expectation. He put his hand on mine and added, “I’m glad you survived the night.”

As we resumed our conversation, I dropped a handful of coins on the table, mementoes from my last visit to Hungary. Alajos picked them up, saw the communist stars and threw them across the room.

“Worthless,” he said with a flash of sudden anger. “Throw them away.”

He pulled a modern forint banknote from his wallet and warned, “This also may be worthless. Our new government ordered special security paper from Germany and the border guards made sure that the freight cars were left on a railway siding overnight. I’m not saying that they had anything to do with its theft but they all drive Mercedes now.”

Alajos rubbed the note between his fingers.

“Good quality,” he said with a wink. “The forgeries look better than the real ones.”

Thirty years ago—at the same table—Alajos had asked me about democracy and the rule of law, and now he recalled my definition. He said, “If democracy is tradition then the sum of our experience is 33 months: in 1918 for two and a half years and in 1956 for ten days. We have no tradition of democracy here.”

“And today?” I asked him.

“You are wondering what has changed?” he replied and, when I nodded, his laugh was bitter. “Everything and nothing.”

I told him of the changes that I had seen on my journey, of hopes betrayed, fears manipulated and people choosing to believe lies rather than face difficult questions. “I also see that nobody in Hungary is in danger of losing weight,” I added.

Since the fall of the Wall, Hungarians had become the fourth most obese nation in the world.

“People eat well in our banana republic,” said Alajos. “It helps them to overlook the ruin around us. Have some more coffee.”

“The ruin?” I said as my cup was refilled.

“Our judges have been tamed and journalists restrained, once again. Enemies are invented and loyal politicians given our property, once again. Now we are just their marketplace.”

“Including Sandor’s shop?”

“Including Sandor. Aldi—with its Hungarian partner—bought the old co-op, undercut his prices, drove him out, drove my son out of his own home like the ÁVH had driven me out. Und so weiter. Und so weiter.”

And so it goes on and on, as ever.

Alajos looked at me, his eyes wide and round in confession. “I knew. I said nothing. I lied.”

“The only difference now is that ideology has been replaced by money,” he said. “I’ll show you after you’ve eaten another croissant.”

After breakfast I was bustled out of the kitchen and into my clothes. His daughters and their children then guided Alajos and me out to the car, holding our hands, asking more questions, helping him into the passenger seat. The oldest child asked how Britain and the US coped with the waves of crime committed by immigrants. When I told her that no such thing was happening, she pulled up a fictitious news story on her phone. As we drove away, I told Alajos that her question had reminded me of the prewar anti-Semitic myths and hoaxes that had ended in genocide.

“Und so weiter. Und so weiter,” he said again.

Together we drove south from Tokaj, following another familiar road along the Tisza. Mosaics of light fell across our path, filtered through the poplars. Fens of reed and willow flanked the roadside. Once more I asked him about his son Sandor but he wouldn’t be drawn.

“Gone, gone,” he simply replied.

When a great body of water opened before us, Alajos began to repeat himself. I let him go on not out of tolerance of an old man’s forgetfulness, but because the story needed to be told again.

“The dam was built by Hungarian and German prisoners in the 1950s,” he said, lifting his cane to point at the wide sweep of concrete.

“I was working not far from here in Tiszalöki,” he explained, gesturing away to the west. “One of the engineer’s wives wanted built-in cupboards. They were popular in Budapest at the time and no functionary’s wife could be without them. I agreed to make her a wardrobe of beech with walnut inlay and—when I was taking the measurements—she told me about the riot.”

Fifteen hundred POWs had been treated no better than slaves, building the hydroelectric dam. Beneath Soviet statues of valiant workers brandishing lightning bolts, they lived on water roots and horseflesh, surviving on 200 calories a day. The suffering was terrible, but there was a worse crime—the lie.

“This stretch of the river had been sealed off. No one could get near the site. It was isolated from the world. The men had been brought from Kiev at night in sealed cattle wagons. Their guards spoke Russian. Their letters to their wives were taken to the Soviet Union to be posted to Hungary. The prisoners thought they were in Russia, as they were supposed to think.”

“But they knew that the war was long over and they demanded to be returned home, home to Hungary, not knowing that they were home, here in Hungary, all the time. Permission was refused so they went on strike, four men were killed, another executed, but one man broke free.”

Alajos then said, “One morning on my way to work—I’d nearly finished the wardrobe—I found an old friend. We thought he had died at Stalingrad, but he’d survived the war. He was the prisoner who had escaped from the dam. But he had become lost in the woods and, not knowing how close to home he was, he had given up hope. After walking for days he had hung himself from a tree not five miles from his village.” He paused for breath. “I found his body, hanging, but I walked away. I told no one. I did nothing.”

Alajos looked at me, his eyes wide and round in confession. “I knew. I said nothing. I lied.”

I felt the shame rise in him, realized that this dear, moral man—shaped by ethical integrity—would be forever haunted by his silence, humiliated by his acquiescence.

The Tiszalök dam, built by forced labor, had been owned by the state until last year when Nemzeti VagyonkezelőZrt—the “National Wealth Management Company”—quietly transferred its ownership to a private concern.

Once again no one objected, no one complained.

As we stood together in the cool sunshine by the Tisza, a sudden shiver ran through me, as if spring had not yet reached the country.

“My generation had not one day of peace,” Alajos confessed, his silhouette rimmed by the cold morning light. “And when in 1989 peace finally came, when the chance to make a better life fell into our laps, when we could finally speak, everyone—even my own children—lost their voice.” He steadied himself on his cane, touched his tricolor lapel ribbon and asked, “Was hättest du getan?”

What would you have done?

—————————————

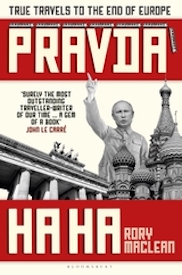

Adapted from Pravda Ha Ha by Rory MacLean, copyright © 2020. Published by Bloomsbury USA.

Rory MacLean

Rory MacLean is the author of more than a dozen books including the UK top tens Stalin’s Nose and Under the Dragon as well as Berlin: Imagine a City. He has won awards from the Canada Council and the Arts Council of England as well as a Winston Churchill Traveling Fellowship, and was nominated for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary prize. He has written about the missing civilians of the Yugoslav Wars for the ICRC, on divided Cyprus for the UN’s Committee on Missing Persons and on North Korea for the British Council. His works have been translated into a dozen languages. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, he divides his time between the UK, Berlin, and Toronto.