The Pleasures of Destroying a Good Book

Crack It, Bend It, Mark It, Love It

It is a sin, she said, to damage the spine. My elementary school librarian showed us a cracked book. The creases and wrinkles looked like an exposed skeleton. After her elegiac presentation, we were sent to the stacks to find books. I handled them with more fear than care. When I got the nerve to peek inside, I eased open the pages as if each text would crumble to dust.

My librarian had good reason for her method: she had to preserve books for years of students. Unfortunately, her warnings made me think that books were meant only to be borrowed. As a reader, I want to inhabit a book as a form of communion. Most books took years to write—and likely a few more years to rewrite. They deserve more than a single read before being consigned to silent prison among their cousins of other genres on untouched bookshelves. Some books become part of my weekly, daily life. Those books are inevitably flattened on my desk. Dog-eared. Highlighted. Circled.

I hope that my poor treatment of books does not seem cavalier. I respect the great art behind book production: type selection, design, layout, illustration, proofing, printing, and binding. Oscar Wilde once reviewed a lecture on bookbinding for London’s Pall Mall Gazette. He found the historical portion of the lecture “very inadequate,” but enjoyed the practical demonstration. The lecturer was T. J. Codeben-Sanderson of Doves Press, perhaps best known for later dumping his press’s type into the Thames. Codeben-Sanderson was in a feud with his business partner, but he also destroyed the type so that it would not be used in “a press pulled otherwise than by the hand and arm of man or woman.” A hundred years earlier, Luddites were smashing textile machines. A hundred years later, books are produced and read purely electronically.

Wilde summarizes Codeben-Sanderson’s sentiment as the “worker diminished to a machine is the slave of the employer, and the employer bloated into a millionaire is the slave of the public, and the public is the slave of its pet god, cheapness.” Yet Wilde cautions “bookbinding is essentially decorative, and good decoration is far more often suggested by material and mode of work than by any desire on the part of the designer to tell us of his joy in the world. Hence it comes that good decoration is always traditional. Where it is the expression of the individual it is usually either false or capricious . . . the danger of all these lofty claims for handicraft is simply that they show a desire to give crafts the province and motive of arts such as poetry, painting and sculpture. Such province and such motive they have not got.” I might not be as dismissive as Wilde here, but I do think books are vessels and mediums rather than museum pieces.

I remember the first time I broke a book. I was reading In the Heart of the Heart of the Country by William Gass as an undergraduate while sitting in the waiting room of a dentist office. My fiction professor said that I needed to read “The Pedersen Kid,” so I combed the text, hoping for some divination that would help my own stories. I enjoyed one phrase so much that I boxed the words as if to catch them. My pencil punctured the page. It felt wrong.

Yet I now must always wound my books. The reading act is as much kinesthetic as imaginative. A marked page has been inhabited by its reader. My annotations, smudges, and notations are appreciations to the canvas that has been provided to me. Yet such tough love results in worn books. Tape saves covers, but once pages split from the binding, they fall like leaves. My first copy of James Agee’s A Death in the Family is thinned, missing so many pages that its front and back covers lean together like shrugged shoulders. I almost want to apologize to it.

My copy of The Best American Short Stories 1983 is split in two. The break appears a few pages into “My Mistress” by Laurie Colwin. Pages 101 and 102, topped by a Post-It, are loose. I’m not sure why the book broke there; Colwin’s story is good, but my favorite is “A Change of Season” by James Bond, the only story I’ve ever been able to find from him. I’m a sucker for great stories about snow. Bond’s tale begins: “Where are there giants to match these mountains?” The collection has two great stories by Ursula K. Le Guin, and ends with the masterful “Firstborn” by Larry Woiwode. It is a heavy story, both in terms of length and subject: the perfect type of narrative to close out a year.

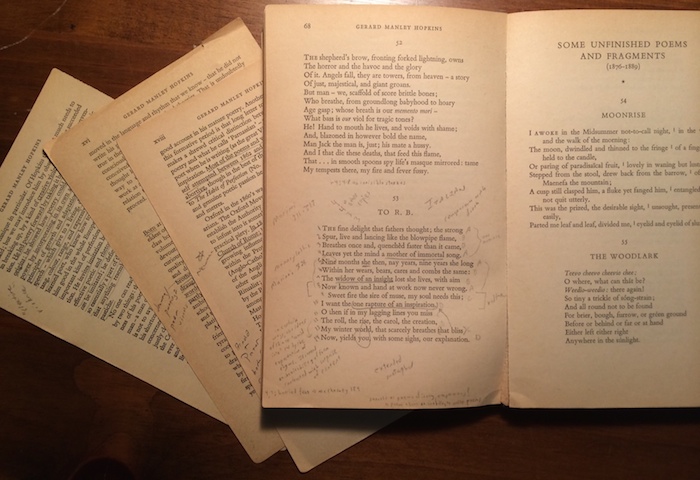

That book stands shoulder-to-shoulder with other anthologies. The pressure keeps it from toppling over. My torn-cover edition of Poems and Prose of Gerard Manley Hopkins is bandaged by type, and rests on my desk. The first few pages of the introduction are loose, and each time I flatten the book to re-read “Inversnaid,” other pages threaten to split. I first read Hopkins as an undergraduate at Susquehanna University. My professor said she didn’t believe in God, but she believed in Hopkins. I didn’t tell her that I wanted to become a priest; I simply volunteered to read “The Windhover” aloud. His verses twisted my brain and contorted my tongue. After class I walked downtown and bought the collection from DJ Ernst Books. It has remained close to me since.

Many of the books I have bruised came from those college years. It was a time of reading and running and writing and late nights that bled into mornings. It was when I met and fell in love with my wife. I looked at words with a new appreciation. I would buy an armful of books each time I went to DJ’s store (he promised to reveal a prized bass fishing hole to me, but we fell out of touch). There was The Portable Faulkner, its cover now ripped, pages yellowed and thin. I bought that for his powerful novella, The Bear. I read Faulkner at the same time I had a course in grammar, with daily sentence diagramming. Faulkner was the first writer who made me want to imprint every page as a sign of appreciation.

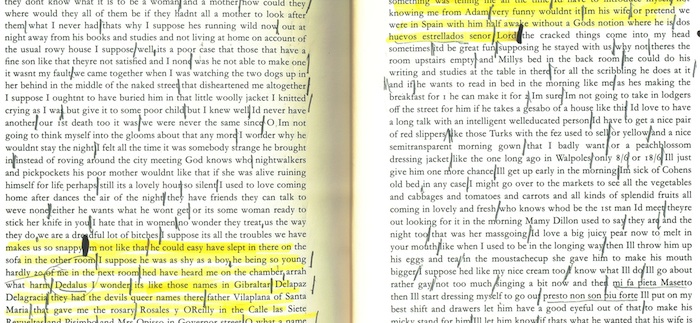

I applied the same method to James Joyce, tattooing Ulysses in hopes I could divine the Irishman’s secrets through manual effort. I purchased a third-hand version that arrived with multiple levels of annotations, so that I not only engaged the text proper, but also responded to the observations of the previous readers. My response descended into penciled slashes in the final chapter. I tried to give Molly breaths, but she didn’t need rest.

Ulysses is messier, but still in better shape, than my copy of The Complete Stories of Flannery O’Connor, a library discard. I’ve beaten down the book in those years past. The binding still holds true, but is a bit worn at “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” O’Connor’s seminal tale has been anthologized into the canon—but is an example of why I support worn books. It is easy to sprint past a text we know when it appears in a fresh book. New pages carry the sheen of speed. Older, darker pages deliver a feel of cloth that attracts my fingers. I want to slow down. “The grandmother didn’t want to go to Florida.” I want to linger in that worn sentence.

Linger, remain, be devoted: the first books I encountered that were worn to pieces were religious texts. Prayer books and pamphlets about saints had found their way from my family’s parishes in Newark and the Bronx to my childhood home. William Gass would smirk, but Catholicism is a temple of texts. In writing about the efficacy of sacred texts, Gass says “each book, to be a proper revelation, and worthy of the trust of the faithful, and in order to sustain itself, and preserve its message, must claim certainty, exclusiveness, a single unwavering interpretation, and an authority which remains total and undiminished.” As he often does, Gass undermines the efficacy of the sacred in order to transfer this spirit to secular texts. When he notes “so many such texts are books made of many books,” he identifies a central truth: each book is birthed from other books. Reading is a sacred act.

Now that I have children, much of my reading is done late. I experience midnight with a book open on my desk, lit by a laptop screen. This late night ritual of resuscitating worn books through reading makes me think of Fanny Howe’s poem, “A Hymn.” “I traveled to the page where scripture meets fiction,” she begins; “The paper slept but the night in me woke up.” Her words bring me to End Zone by Don DeLillo, a book I have recommended more than any other. I return to DeLillo’s football novel each August. I pause at sentences I underlined in years past: “A passion for simplicity, for the true old things, as of boys on bicycles delivering newspapers, filled our days and nights that fierce summer. We practiced in the undulating heat with nothing to sustain us but the conviction that things here were simple. Hit and get hit.”

The spine of End Zone nearly breaks between pages 118 and 119. Part Two of the novel is a parodic yet admiring send-up of the big game narratives of sports novels. Logos College meets Centrex, their rival. DeLillo drowns the reader in football speak, offering metafictive observations next to flashbacks. He offers readers a rest within a paragraph about the need for plays to have names. “Coaches stay up well into the night in order to name plays. They heat and reheat coffee on an old burner.” I wrote language in the margin, the type of annotation that frustrates teachers. But these notes are truly letters to myself: reminders of how to settle back into the feeling I had during the previous year. Heat and reheat. Read and reread.

A similar refrain informs the book I have burdened and broken the most: The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene. I taught the novel for a decade to students at a public high school. No teacher had touched the books for years; I found them on the bottom shelf of the bookroom. Dust had silvered the white covers. I then hoarded the books in my room.

My book number is 70-4. The cover fell off. I taped it together, but it only holds the contents like a folder. The pages have been handled so much that their edges are rounded, and frayed. Tucked between pages 122 and 123 is a sheet of goldenrod paper that contains a list of the book’s scenes. The novel’s whiskey priest, on the run from a fascist government bent on eradicating all vestiges of religion, spends the night in a jail cell. He is not alone. A couple is having sex in the corner. Their act does not bother the priest, but it does bother the sensibility of a pious woman: “Why won’t they stop it? The brutes, the animals.”

“Don’t believe that,” the priest says. “It’s dangerous. Because suddenly we discover that our sins have so much beauty.” I have read those sentences aloud year after year, from a copy of the book whose cover shifts in my palm. However damaged, it will never crumble. Words are stubborn. They survive. A broken book is often a book wrecked by love. How often we experience that emotion—our hearts wrenched, our souls stirred—and yet we return to those books, those loves, as if they were brand new.