The Parkmaker and the Formgiver: On the Creative Friendship That Reshaped the American Streetscape

Hugh Howard on the Collaboration Between Frederick Law Olmsted and Henry Hobson Richardson

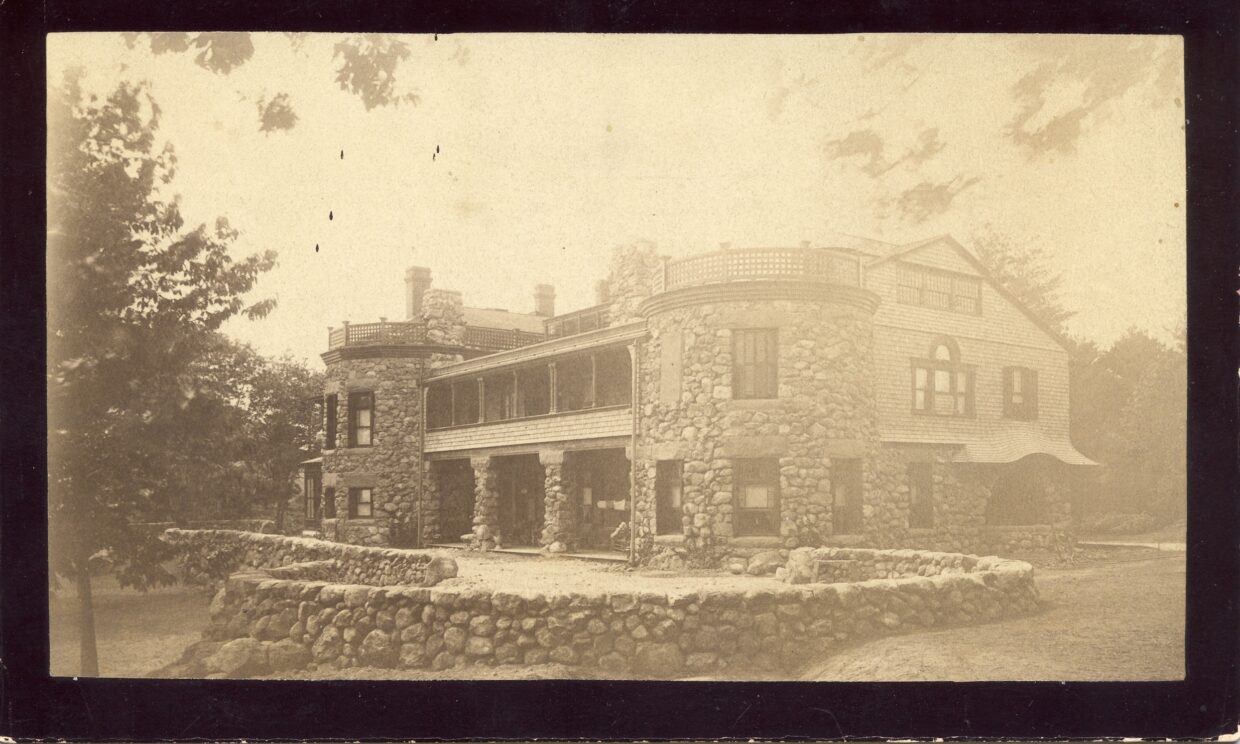

Feature image: The Converse Library, in Malden, Massachusetts, a Richardson design amid its Olmsted landscape. Houghton Library/Harvard University.

High in the Rocky Mountains, in January 1887, a locomotive chugged up a steady grade, coal smoke billowing from its stack. To the surprise of the passengers, the brakeman brought the train to an unscheduled stop at a tumbledown array of workers’ shanties. Once a busy place with a general store, two hotels, saloons, and even a school, Sherman Station, Wyoming, was becoming a ghost town.

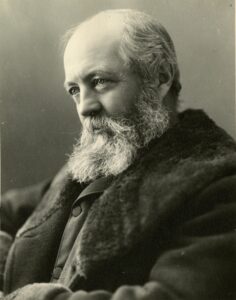

A pensive Frederick Law Olmsted, in 1893, shortly before his retirement. National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

A pensive Frederick Law Olmsted, in 1893, shortly before his retirement. National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

A precisely dressed gentleman exited the Pullman car. His gait uneven, the result of a carriage accident long before, sixty-five-year-old Frederick Law Olmsted, a man widely known as America’s first and finest parkmaker, headed up a nearby hill.

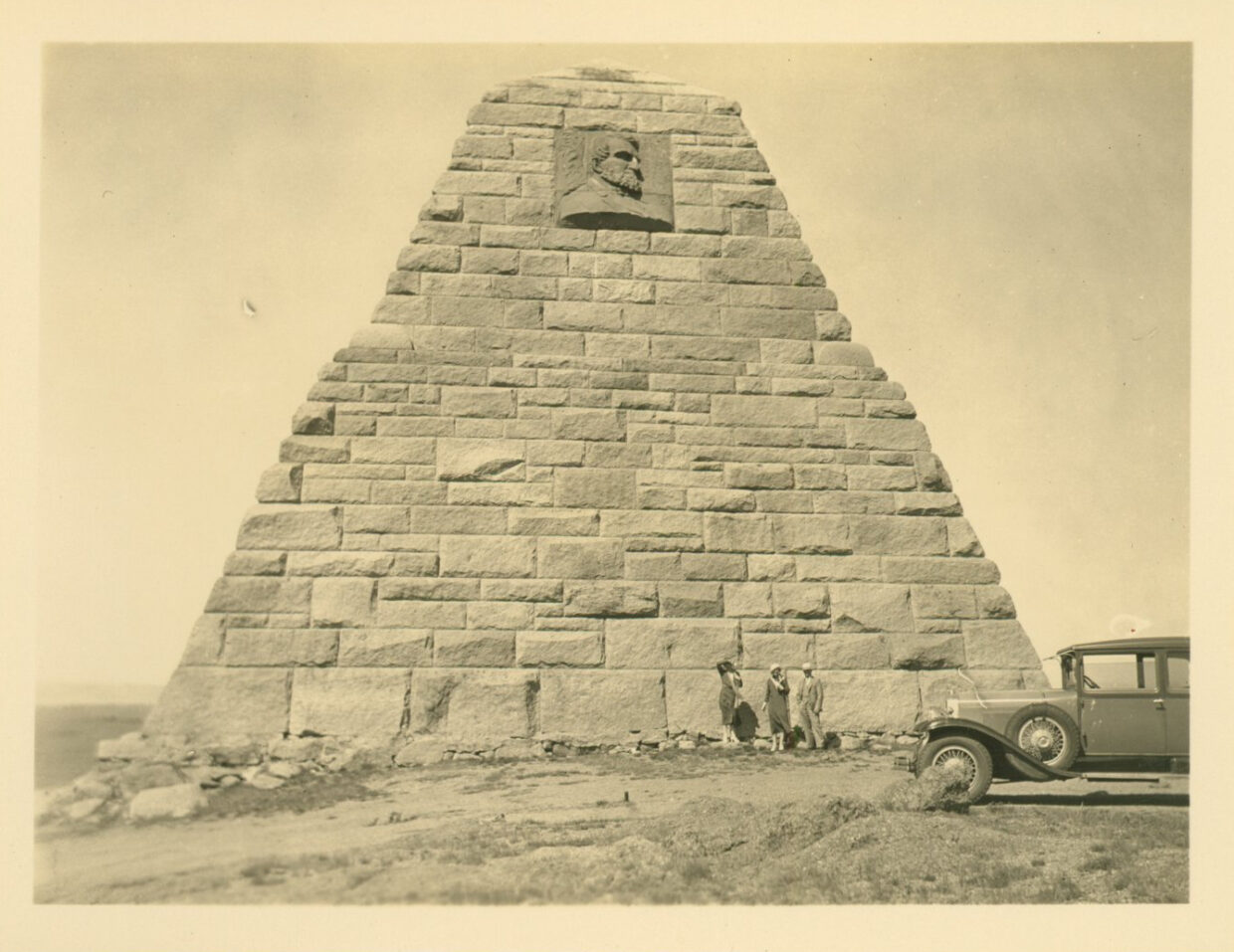

His destination was a rugged granite pyramid that celebrated the completion of the transcontinental railroad. He wished to see “our monument,” as he described the sixty-foot-tall structure, the work of architect Henry Hobson Richardson, who had benefited from Olmsted’s critiques of early sketches. Olmsted approved: “I never saw a monument so well befitting its situation,” he wrote a few days later, “or, a situation so well befitting the special character of a particular monument.”

British portraitist Herbert Von Herkomer made a charcoal study of Henry Hobson Richardson in the architect’s last months; the oil painting he completed in 1886 was regarded by friends and family as a very good likeness. National Portrait Gallery/Smithsonian Institution.

British portraitist Herbert Von Herkomer made a charcoal study of Henry Hobson Richardson in the architect’s last months; the oil painting he completed in 1886 was regarded by friends and family as a very good likeness. National Portrait Gallery/Smithsonian Institution.

Yet the sight was accompanied by sadness, since Olmsted had been a pall bearer eight months before for the irrepressible and irreplaceable Richardson. The funeral service, held at Trinity Church, in Boston, his friend’s best-known work, followed the big man’s death, at forty-seven, of kidney failure.

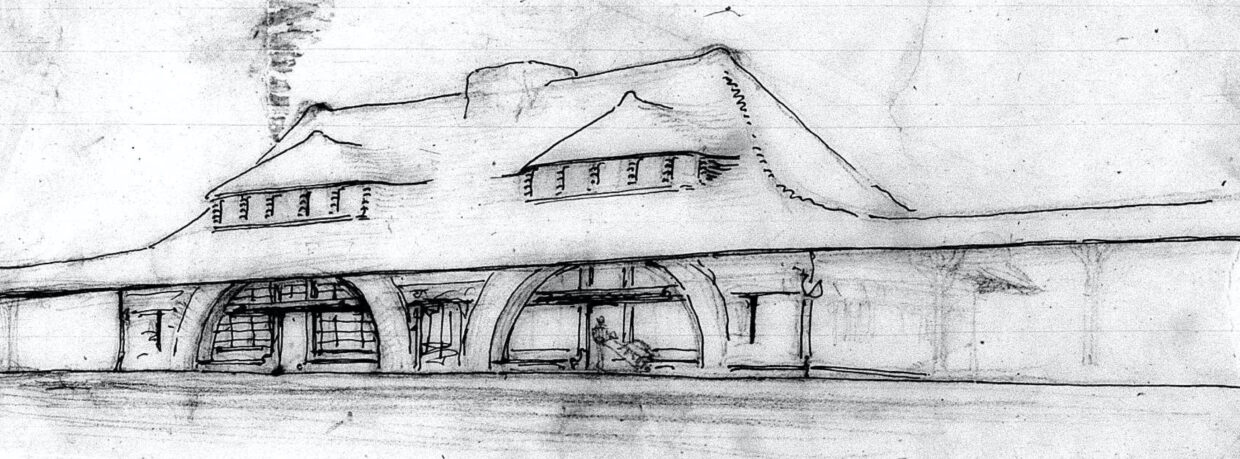

Richardson had been a formgiver. As tightly packed cities fanned out, he devised prototype suburban rail stations, which Olmsted had landscaped. Thanks to them, the nation’s early commuters had experienced a welcoming sense of escape from what Samuel Clemens called the “dusty and deafening railroad rush.”

The Ames Monument atop of its eminence, pictured ca. 1930. The bas relief at the apex, the work of sculptor August Saint-Gaudens, is of Congressman Oakes Ames, one the prime movers in the building the transcontinental rail line. University of Wyoming/American Heritage Center.

The Ames Monument atop of its eminence, pictured ca. 1930. The bas relief at the apex, the work of sculptor August Saint-Gaudens, is of Congressman Oakes Ames, one the prime movers in the building the transcontinental rail line. University of Wyoming/American Heritage Center.

The nation had had no history of libraries open to all when Richardson had been hired to create a public library. The half-dozen freestanding examples he left behind were being widely copied; when Andrew Carnegie’s launched his national program, he looked first to Richardson’s libraries, with their linked book alcoves and reading rooms.

Richardson had designed a wide range of buildings for a country in which the agrarian was fading, replaced by an industrial culture of growing cities. He and Olmsted, independently and together, had offered fresh design solutions.

Olmsted felt acutely the loss of his dear friend, whom he acknowledged as “the greatest comfort and the most potent stimulus that [had] ever come into my artistic life.” Olmsted himself would carry on, creating major works like the Biltmore Estate in North Carolina, the Stanford University campus, and Chicago’s 1893 Columbian Exhibition. His memory remains honored today in many cities where his parks still improve the quality of life.

Thanks to them, the nation’s early commuters had experienced a welcoming sense of escape from what Samuel Clemens called the “dusty and deafening railroad rush.”

In contrast, the Wyoming monument is rarely visited in the 21st century. After the rail bed was rerouted, Sherman vanished, leaving the stone pyramid largely forgotten in its high meadow. Posterity would treat Richardson much the same. As the nation’s most-admired architect in his last years, his design ideas became received wisdom; in death, he became an architect’s architect, admired in the profession, known to students from architectural texts. But his broader fame faded.

As House Beautiful observed, “The low stone station of the Richardson type nestles beside the track . . . as beautiful and peaceful as a country lane.” He and his apprentices created dozens of such stations, including this one in North Easton, Massachusetts, while Olmsted’s firm oversaw the landscaping of at least three times as many. Houghton Library/Harvard University.

As House Beautiful observed, “The low stone station of the Richardson type nestles beside the track . . . as beautiful and peaceful as a country lane.” He and his apprentices created dozens of such stations, including this one in North Easton, Massachusetts, while Olmsted’s firm oversaw the landscaping of at least three times as many. Houghton Library/Harvard University.

The public may forget, but friends remember. On this particular January day in 1887, standing alone in the whistling wind beneath the towering western sky, the grieving Olmsted found his eyes “half drowned” as he shed tears of mourning.

*

When they met immediately after the Civil War, Richardson and Olmsted lived in rural Staten Island and ferried daily to Manhattan to their respective offices. With Central Park already to his credit, Olmsted labored on the construction of Prospect Park in Brooklyn, while Richardson, sixteen years Olmsted’s junior, was just months into his professional practice.

Their working relationship began in 1868 when Olmsted asked Richardson to design the tomb for a burial site in Washington’s Congressional Cemetery. The following year, Richardson returned the favor, inviting Olmsted to join him in designing the Buffalo State Asylum for the Insane. The result would be a great leap forward for American architecture and the first flowering of an important artistic alliance.

Having become one of the busiest ports in the world, Buffalo was a prosperous place, but its rapid growth had also produced a “lunatic problem.” Persons with mental illness had long been regarded as a private matter for families, but “distracted persons” had begun wandering the streets of large cities. Asylums for the care of mentally ill persons had become a priority, and the New York State legislature, in March 1869, authorized construction of one such facility in Buffalo.

Richardson’s first built designs, which included a pair of parish churches, a railroad office, and a handful of houses, helped get him the job, as did his gregarious personality, which had won him many friends in New York. But he recognized his Staten Island neighbor brought expertise he needed, since Olmsted had landscaped several other mental health facilities. According to the best medical thinking of the day, patients were inherently good and, if given proper care in a serene setting away from the ills and distractions of the city, their confused minds might find a new equilibrium. In time, the theory proved sound, as the bucolic-rather-than-Bedlam approach to mental illness permitted roughly two out of three patients to return to their communities as functional members of society.

Richardson set to work. A native of New Orleans educated at Harvard, he had avoided choosing sides in the Civil War, expatriating himself to study architecture at Paris’s Ecole des Beaux Arts. On his return to the USA, Richardson had brought a deeper reservoir of knowledge and training than most of his American competitors.

The asylum’s program called for a central administrative building flanked by living spaces for hundreds of male and female patients. Matching wings would be divided into sequential wards, as Olmsted expressed it, “for so placing the violent and noisy patients, that the quiet and convalescent would escape disturbance or annoyance from them.” But the charge effectively ended there, leaving the solution to its designers.

The asylum complex was very much the work of two heads working as one, a therapeutic place that served a common goal of enhancing the health, strength, and morality of those who resided there.

Richardson first considered a mansion-like structure with a linked series of cottages, but that notion never made it beyond the pages of his sketchbook. He veered next toward Victorian Gothic, designing a main building that featured turrets with conical roofs like a medieval castle. He added a bulky central spire with a large rose window—in France, he had seen cathedral architecture adapted for public institutions—but this preliminary plan pleased neither him nor his clients. Still, the buoyant Richardson was far from discouraged. As he said to Olmsted later, “Never, never, till the thing [is] in stone beyond recovery, should the slightest indisposition be indulged to review, reconsider, and revise every particle of his work.”

Eventually Olmsted asked the right question.

A some-time farmer, nurseryman, and journalist, he had stumbled upon landscape design by accident when a friend suggested he apply for the job of superintendent of New York’s Central Park project. He still couldn’t quite call himself an artist—“I don’t feel strong on the art side,” he admitted—but he was a deeply practical man and superb manager who happened to possess a gift for seeing the capabilities of raw landscape. The Buffalo breakthrough came when he asked whether Richardson might consider breaking the line of the façade. Rather than line up the buildings as if on a city street, why not set back the pavilions, one to the next? Richardson added curved corridors between the structures, increasing light and circulation and making the whole less monolithic from the front. To the rear, the open arms of the approaching wings would embrace farm lands that Olmsted expected would provide both food for the institution and healthful labor for patients.

Olmsted’s 1871 plan of the grounds for the Buffalo State Asylum. The whole is anchored by the sprawling footprint of the main hospital building. Courtesy of Francis Kowsky.

Olmsted’s 1871 plan of the grounds for the Buffalo State Asylum. The whole is anchored by the sprawling footprint of the main hospital building. Courtesy of Francis Kowsky.

The resulting assemblage of eleven structures—ten pavilions, five on either side of the main block—assumed a V-formation that resembled a skein of geese in flight. Olmsted added a carriage path along the margins of the property for peaceable rides in what became self-contained countryside. Hedges and fences screened the hospital grounds from prying eyes, enhancing the sense of safety and seclusion for patients. Olmsted specified breaks in the tree line to permit passersby views of the hospital’s handsome façade.

Richardson incorporated elements of the Romanesque into his twin-towered brownstone building, including characteristic round arches; thus, the Richardson Romanesque was born, a style that would be imitated across the United States, from Georgia to Texas and on to Seattle. But the asylum complex was very much the work of two heads working as one, a therapeutic place that served a common goal of enhancing the health, strength, and morality of those who resided there.

The great mass of Richardson’s immense asylum might have resembled a fortress, but surrounded by Olmsted’s mature plantings (this picture was taken ca. 1900), the hospital conveyed no air of incarceration. Courtesy of Francis Kowsky.

The great mass of Richardson’s immense asylum might have resembled a fortress, but surrounded by Olmsted’s mature plantings (this picture was taken ca. 1900), the hospital conveyed no air of incarceration. Courtesy of Francis Kowsky.

*

In the mid-1870s, Richardson moved to Boston. When Olmsted followed a few years later, his friend offered to design him a house—“a beautiful thing in shingles?”—adjacent to his own. Though Olmsted instead bought an existing dwelling nearby, the connection between the men, their work, and their families gained a new permanence. As the teenaged Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., Olmsted’s youngest child, remembered, “I was in and out of [their] house and office all the time, with father and with the Richardson children.”

Olmsted had been drawn to Massachusetts in part by a large park project, the seven-mile sequence of open spaces, parkways, and waterways nicknamed the Emerald Necklace. At Olmsted’s request, Richardson had already designed the Boylston bridge, a centerpiece of the first of those parklands, the Back Bay Fens. As neighbors in the town of Brookline, they would continue to collaborate regularly, though each maintained a busy independent practice out of an office attached to his home.

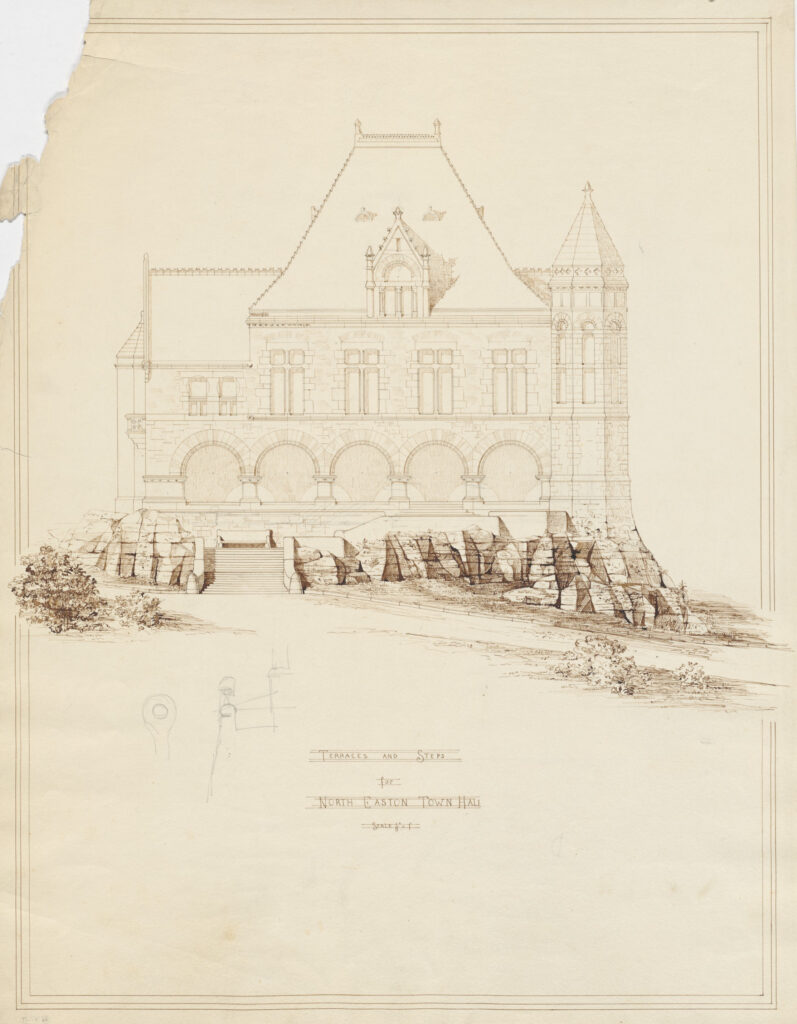

Together they reinvented the downtown of North Easton, Massachusetts, introducing works that included a Richardson library, an Olmsted-designed Civil War monument of stacked boulders, and a train station. The new town hall in particular spoke for the way their minds melded. The Romanesque building with a tall corner tower was settled into its site by Olmsted, and the way he softened the line of demarcation between structure and site meant Richardson’s building looked—and still looks—like it belonged there, offering a large lesson to a new generation of designers.

This lightly penciled drawing of the North Easton town hall was the work of a Richardson draftsman; the landscape plan added in bolder brown ink—most probably by Olmsted himself—displays the imaginations of Richardson and Olmsted engaged on the same sheet. National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

This lightly penciled drawing of the North Easton town hall was the work of a Richardson draftsman; the landscape plan added in bolder brown ink—most probably by Olmsted himself—displays the imaginations of Richardson and Olmsted engaged on the same sheet. National Park Service, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site.

Another joint work was a large house in nearby Waltham, Massachusetts, constructed in the Shingle Style, a manner Richardson pioneered with his early apprentices Charles McKim and Stanford White, who would go on to found perhaps the most influential architectural firm of the next generation, McKim, Mead, and White. Visitors to Stonehurst, as the Waltham house would be known, encountered an open plan, one of Richardson’s most influential architectural innovations.

For proper Bostonians accustomed to houses that reflected class and social distinctions, the continuous space of the living-hall plan was a shock. Rooms at the time usually had discrete purposes, but Richardson disregarded that rule of thumb, making the experience of the room something new, with its fifty-foot depth, front to back, and 114-foot length. The expanse was informal, vast, even exposed, and unbroken by so much as a column. The American house would, quite simply, never be the same, thanks to Richardson and the later architects who saw his work as a touchstone for new answers.

As the leading 20th-century scholar of Richardson wrote, “the geological inspiration at Stonehurst create[s] a sense of timeless continuity between house and site.” Robert Treat Paine Trust/Stonehurst Archives.Frank Lloyd Wright was prominent among those who followed the lead of America’s first celebrity architect. When Wright designed a home for his young family in Oak Park, Illinois, in 1889, he had just read Richardson’s biography, a book that Olmsted had conceived and sponsored—it was the first biography of an American architect—and Wright built a Shingle Style house. His indebtedness to Richardson would reappear often, as Wright had a fondness for Richardsonian arches, stone piers, and low rooflines. Like many architects of his generation, Wright maintained what he himself admitted was “secret respect, leaning a little toward envy . . . for H.H. Richardson.”

As the leading 20th-century scholar of Richardson wrote, “the geological inspiration at Stonehurst create[s] a sense of timeless continuity between house and site.” Robert Treat Paine Trust/Stonehurst Archives.Frank Lloyd Wright was prominent among those who followed the lead of America’s first celebrity architect. When Wright designed a home for his young family in Oak Park, Illinois, in 1889, he had just read Richardson’s biography, a book that Olmsted had conceived and sponsored—it was the first biography of an American architect—and Wright built a Shingle Style house. His indebtedness to Richardson would reappear often, as Wright had a fondness for Richardsonian arches, stone piers, and low rooflines. Like many architects of his generation, Wright maintained what he himself admitted was “secret respect, leaning a little toward envy . . . for H.H. Richardson.”

*

Olmsted and Richardson were an unlikely pair. Olmsted was short and slight; by the end of his life, the Falstaffian Richardson ballooned to 350 pounds. Somber and serious, Olmsted usually seemed preoccupied with big thoughts; in contrast, Richardson burst into rooms full of laughter, unafraid of tears.

Despite their differences, the two together evolved a fresh vision for a country in transition. When Olmsted was a child in the 1820s, nature was near—no one in the United States lived more than two miles from undeveloped land. Over the decades he witnessed an eight-fold increase in population and designed almost one hundred city parks across the country to invigorate the lives of city dwellers newly separated from what he called “the scenic.”

Whatever their era, the best buildings and constructed landscapes exist not merely in the moment; rather, they defy time.

There was little new in American architecture when Richardson returned from Paris, in 1865, and set about moving beyond the layering of European forms to create, as he put it, a “bold, rich, living architecture.” In a way that no other building in the United States ever had, his Trinity Church became a global destination, a work admired by architects and churchmen from around the world. Later, his Marshall Field Warehouse helped establish Chicago as an architectural mecca and inspired such gifted followers as Louis Sullivan.

Richardson’s plans produced open, shared spaces that flowed into one another rather than traditional boxes that were subdivided into smaller boxes. He left an indelible imprint on the designs of homes, libraries, hospitals, courthouses, academic buildings, transportation hubs, stores, offices, churches, and other buildings. “For a space of time,” remembered an architect whose career launched as Richardson’s ended, “we were all Richardsonians. . . . How could we do otherwise? Here was a real man at last.”

Whatever their era, the best buildings and constructed landscapes exist not merely in the moment; rather, they defy time. How else to explain, a century after its completion, how Trinity Church compelled I. M. Pei to clad his John Hancock Building in mirrored glass, the better to reflect the neighboring church? How else to account for the survival of so many Olmsted parks largely unchanged and cherished for all the virtues Olmsted designed into them decades ago?

Richardson imposed his personality on his buildings, creating an architectural manner that was original and individualistic. Olmsted left an imprint on the American landscape more expansive than anyone before or since. These dissimilar men—the pragmatist Olmsted, a manager, futurist, and park man, and the artist Richardson, right-brained, frequently impractical, and instinctive—improved the world in which their fellow citizens lived, worked, learned, and played. Their shared understanding of the unfolding panorama of American life in their time informs ours.

_________________________________________________________________

Adapted from Architects of an American Landscape. Used with permission of the publisher, Grove Atlantic. © 2022 by Hugh Howard.

Hugh Howard

Hugh Howard is the author of numerous books on architecture and design, including Architecture’s Odd Couple; Dr. Kimball and Mr. Jefferson; Thomas Jefferson: Architect; Houses of the Founding Fathers; and a memoir, House-Dreams. He lives in New Hampshire.