The Obscure Editions of Jane Austen Novels That Made Her Internationally Known

Elizabeth Bennet Meets Pulp Fiction

It is well known that Jane Austen’s reputation lay dormant for 15 years or so following her death in 1817. The orthodox view is that she reached a wider English audience only after Richard Bentley (1794–1871) revived her work for his Standard Novels reprint series in 1833. But Bentley, although he was a catalyst, is not the true hero of this Sleeping Beauty story.

His books were also not as cheap and accessible as scholars, taking Bentley’s advertisements at their word, have assumed. Bentley emphasized the inexpensive nature of his handsomely produced compact volumes, ornamented with elegant frontispiece illustrations and title-page vignettes: “price only 6s.” and “Cheap Edition.” He was an early adopter of publisher-issued bindings in cloth, and his prices reflected not only the paper savings of his three-in-one-volume format but also the sudden freedom from traditional leather bindings.

Scholars have amply recorded and praised Bentley’s reprintings of Austen as “Standard Novels,” stressing their authority (that is, he paid for proper copyrights) and importance as Austen’s reputational turnkey. As a result of this attention, Bentley’s sedate volumes are now highly sought after. However, Bentley’s influence upon Austen’s reception may be greatly overplayed, for his books were quickly joined by far cheaper versions with a wider impact. The role of these less-princely reprints has been largely ignored in the dominant fairy-tale version of Austen’s reception.

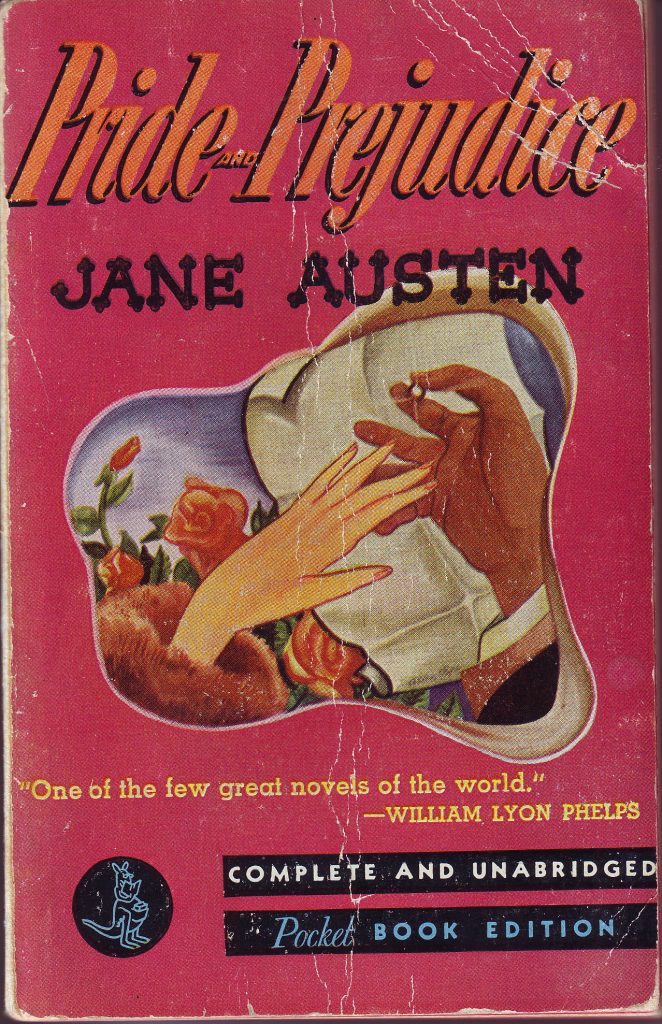

A 25-cent Pocket Books reprint of Pride and Prejudice (New York: Pocket Books, Inc., 1940). Author’s collection.

A 25-cent Pocket Books reprint of Pride and Prejudice (New York: Pocket Books, Inc., 1940). Author’s collection.

My focus is therefore not on Bentley’s well-touted reprints but on the neglected books of his down-market competitors. Bentley’s prices and his own claims to cheapness, however, do help to calibrate what came next. In 1811, the first edition of Sense and Sensibility had sold in three volumes for 15 shillings in boards—a proper binding remained extra. In December 1815, advertisements for the first edition of Emma raised that price by six shillings to a guinea, or £1.1s., for its three volumes in boards.

Hand-press books in Austen’s lifetime remained luxury items, and her novels appeared in modest runs—possibly as low as 750 for Sense and Sensibility and as high as 2,000 copies for Emma. Then, in 1833, Bentley introduced his well-made reprints of Miss Austen in single volumes at six shillings each in durable publisher’s bindings of plum-colored linen, or maroon-ribbed cloth, with paper labels. Royal A. Gettmann, the first chronicler of Bentley’s Standard Novels series, points out that “the expenditure on advertising was liberal” and costs high enough so that “the break-even point was about 3300 copies,” with average runs per title under 4,000.

Years later, fellow publisher George Routledge remarked of the early 19th century that “in those days an edition of 500 was considered large, and one of 2,000 enormous.” Thus, Bentley’s runs were ambitious for the time and his six-shilling price tag comparatively low. By means of stereotyping, a new method of reprinting that led to cheaper book prices, Bentley periodically continued to reissue identical Austen volumes through 1866; he briefly lowered his price still further in the 1840s.

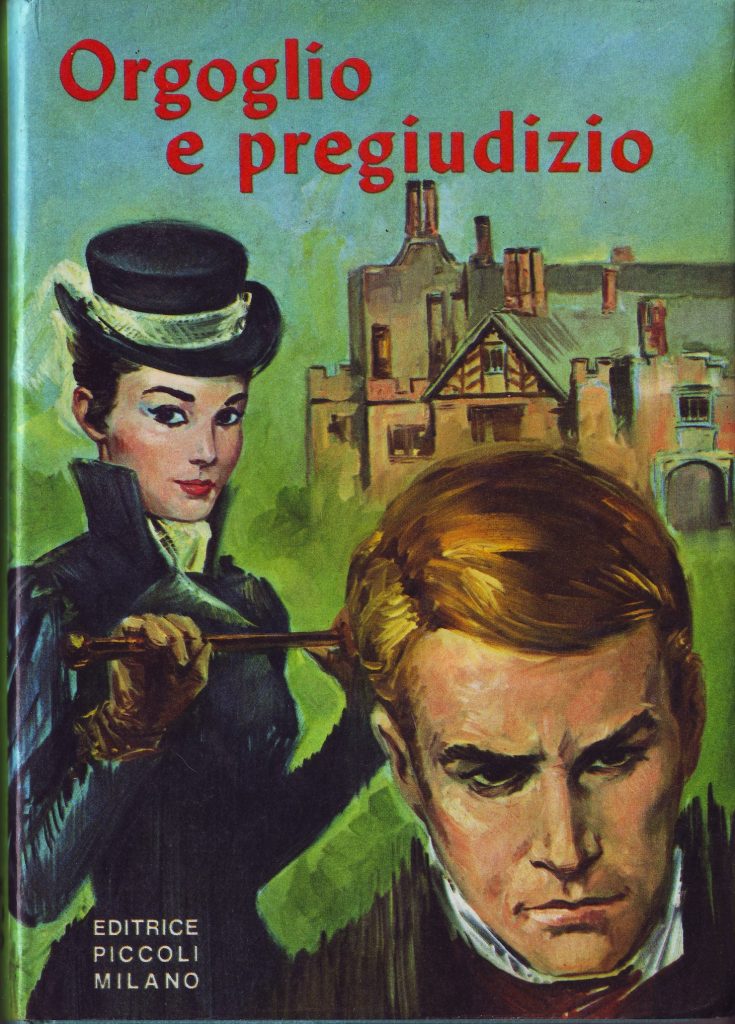

Orgoglio e pregiudizio, translated by L. Corsini and illustrated by Cassinari (Milano: Piccoli, n.d.); Ritorno a te (Bologna: Capitol, 1962); and Orgullo y prejuicio, translated by Costa Clavell (Barcelona: Mundilibros, 1973). Author’s collection.

Orgoglio e pregiudizio, translated by L. Corsini and illustrated by Cassinari (Milano: Piccoli, n.d.); Ritorno a te (Bologna: Capitol, 1962); and Orgullo y prejuicio, translated by Costa Clavell (Barcelona: Mundilibros, 1973). Author’s collection.

Meanwhile, the cost for an upmarket first edition of a new novel in the three-decker format made popular by Sir Walter Scott stubbornly held at £1. 11s. 6d. until the mid 1890s. No wonder, then, that scholars, comparing Bentley’s prices to those for first editions, have hailed him as Austen’s reputational Prince Charming.

Bentley’s relative bargains certainly pushed Austen into public visibility, but his six-shilling reprints were still not within easy reach for a skilled worker earning twenty shillings per week, let alone an unskilled laborer earning half that wage. Even with books at six shillings, bookselling remained “a peculiarly rotten system of providing only for the select few.” In 1846, after the copyright of Austen’s first three novels expired and competition by upstart publishers increased, the fastidious Bentley was briefly forced to drop his price to 2s.6d. per volume, adjusted by 1848 to 3s.6d.

Surviving Bentley copies of Austen from this period are rare, but those in their original publisher’s bindings bear witness on their spines to his momentary drop in price, itself a fraught response to the radical changes in the marketplace wrought by cheaper fare. With his books selling for 2s.6d. and 3s.6d., before climbing safely back to his preferred six-shilling rung, Bentley briefly found himself slumming it—offering Austen at roughly one-twelfth to one-ninth the cost of brand new fiction.

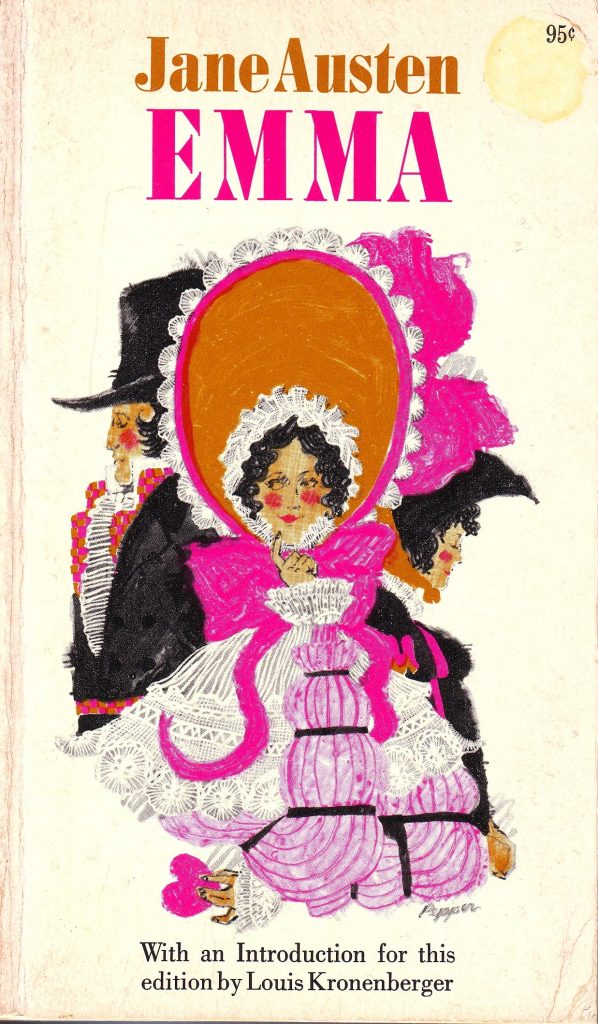

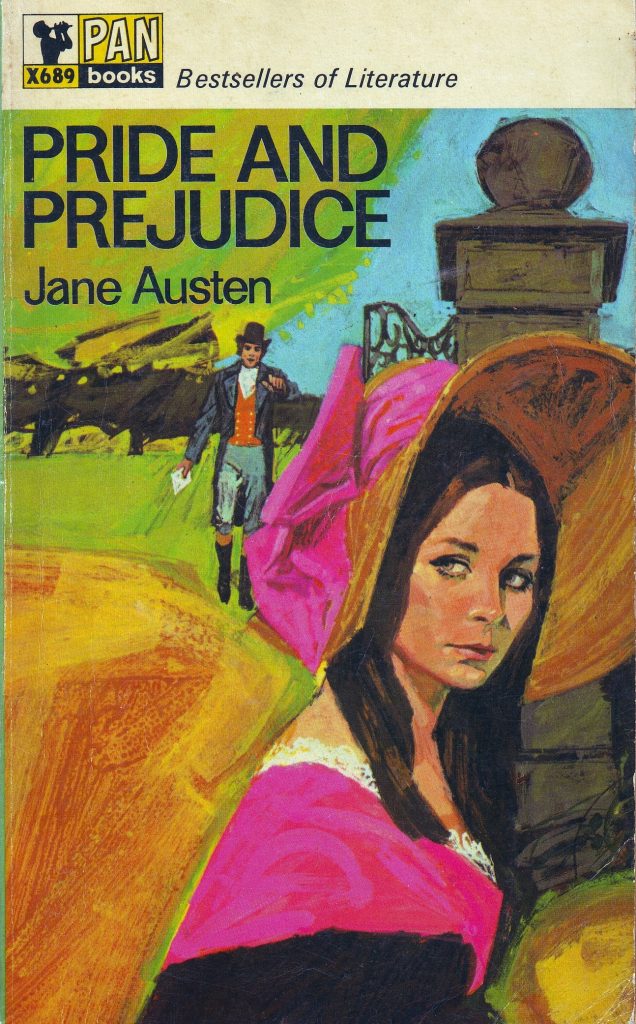

Example of pinked paperback edition from the 1960s. Author’s collection.

Example of pinked paperback edition from the 1960s. Author’s collection.

Inside, the original endpapers of these rare Bentley survivors claim: “Cheapest Collection of Novels in the English Language.” Even so, Bentley’s much-hailed “cheap” books remained the purview of well-to-do Victorian clients such as socialite Lady Molesworth of Pencarrow, who owned a complete set of his Austens, dated 1856, in an aftermarket binding of green publisher’s cloth prettily stamped with a gilt design.

Far cheaper reprintings of Austen in astonishingly large numbers and unprecedented variety were then newly reaching working-class audiences. Fluctuating production values, including paper quality, meant that not all of these other 19th-century versions aged well. Few ended up in libraries. And yet these other reprints, dismissed as dubious by all but the occasional antiquarian in favor of the sturdier stuff of authoritative firsts or scholarly editions, nevertheless launched Austen’s global celebrity.

By tracking the most popular author since Shakespeare through her least authoritative incarnations, I urge a more inclusive reception history. These urgings occasionally read against the grain of bibliographical values that have deep-rooted prides and prejudices. In 1905, Henry James sneered at Austen’s proliferation in “pretty reproduction in every variety of what is called tasteful, and in what seemingly proves to be saleable form.”

From such a rarefied point of view, bibliography itself goes slumming in my project, for I seek to raise to scholarly visibility the schlockiest of Austen reprints: tawdry shilling or sixpence versions sold at the bookstalls of 19th-century railway stations, penny and half-penny serializations, schmaltzy Victorian gift books, giveaways in advertising campaigns, reprints for coal miners in a religious temperance society, flimsy wartime formats for soldiers, and a plethora of dodgy paperbacks for all manner of readers.

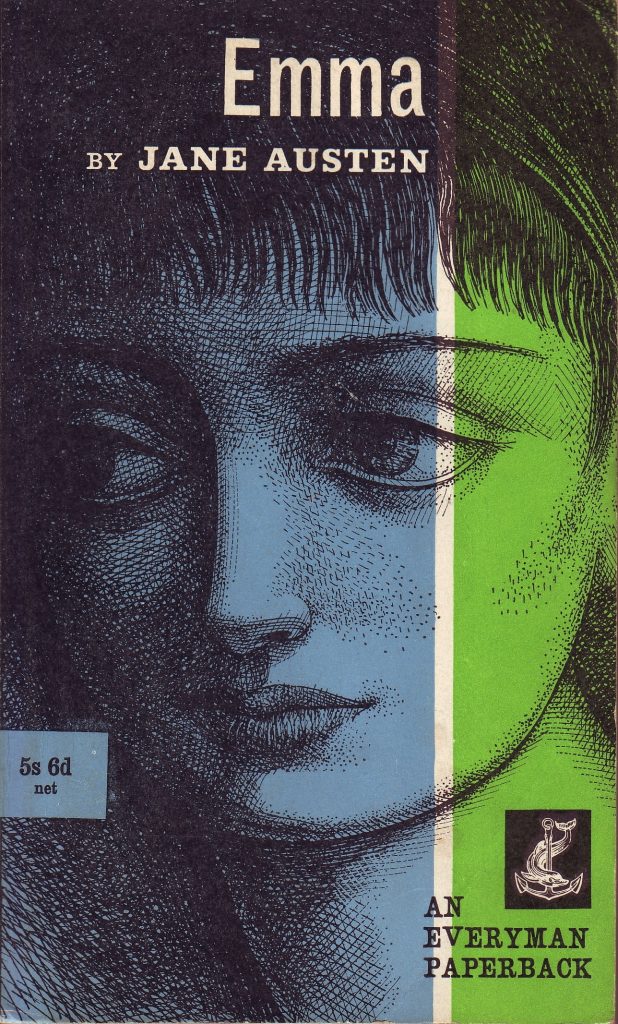

An Everyman Library paperback reprint of Emma (London and New York: Dent and Dutton, 1963). Author’s collection.

An Everyman Library paperback reprint of Emma (London and New York: Dent and Dutton, 1963). Author’s collection.

The books I discuss practice crude sensationalism and commit fashion errors. Many contain sloppy misprints and some prove deeply misguided in their choice of decoration or embellishment. I overlook these flaws in the search for a more complete picture of the immense range of formats and communities that participated in Jane Austen’s literary celebrity over the first two centuries of her literary afterlife. I risk bibliographical misdemeanors in the interest of a fuller and more hands-on reckoning of Austen’s popular reception.

Many other scholars have already written articulately about the Cult of Jane. For the most part, however, the author’s fame continues to be measured by the published responses from critics, scholars, and fellow writers—usually led by Sir Walter Scott, who famously reviewed Emma in 1816—rather than by the manner in which her books were marketed to the general public. In my criticism of the narrowness of Austen studies, I join voices with Devoney Looser, whose recent book The Making of Jane Austen brought to light many early Austen influencers unrecognized by the academy.

Both she and I remark on the perpetual recruitability of Jane Austen for this or that ideological cause. Similarly, Annika Bautz has let fresh air into the vaults of Austen scholarship with research into sixpenny editions of Pride and Prejudice, drawing attention to a neglected working-class format. As James’s sneer indicates, the lowbrow reprints of Austen, so popular with reading publics beyond the academy, have long been passed over for treasured first editions. Even so, the history of pearly firsts does not string together into the strong chain of reception history.

Admittedly, important first editions surviving in scholarly libraries may yet tell us more, as Juliette Wells argues in Reading Austen in America about the earliest American printings in 1816 and 1832–33. The print runs of these Austen firsts, however, have misled scholars about her American reception. Fluctuations and drops in subsequent demand, including sporadic decades in 19th-century America when, to put it bluntly, Jane Austen barely maintained a pulse in the American book market, challenge notions of a presumed “gradual rise of Austen’s renown” in America.

Her market share in America revived only toward the end of the 19th century and by means of iffy and often unrecorded publisher’s series, where she played an extra rather than a starring role. And sometimes historians hail the wrong books as “firsts.” For example, when it comes to the modern editing of Austen, Kathryn Sutherland claimed that, in 1923, Oxford University Press editor R. W. Chapman forged a crucial “first” that laid down a template for future modern editions. And yet, to grant Chapman’s edition that status is to ignore the trailblazing “school edition” of his wife, Katharine Metcalfe.

Another pinked paperback edition from the 1960s. Author’s collection.

Another pinked paperback edition from the 1960s. Author’s collection.

An unrelenting selectivity regarding which books are worthy of study and ownership has made even the best academic discussions and the most detailed historical accounts of Austen’s reception history relatively clipped and top-heavy affairs. The exclusionary choices of Austen’s established bibliographical record demand revision, because they have painted the wrong picture of Austen’s early reputation.

Sir Geoffrey Keynes (1887–1982) and David Gilson (1938–2014), Jane Austen’s two most influential bibliographers, shaped the collecting strategies of librarians and individuals who turn to scholarly inventories to find out which editions are worth keeping. Keynes’s groundbreaking Jane Austen: A Bibliography (1929) and Gilson’s more voluminous A Bibliography of Jane Austen (1982) are monumental contributions to the study of Jane Austen. Current scholars of Austen, including me, continue to rely upon Gilson, whose bibliography remains an indispensable and oft-cited reference text.

Inadvertently, however, Keynes and Gilson constrict current understanding of Austen by narrowing down the versions of her books retained for study. Alberta Hirshheimer Burke (1906–1975), the best-known private collector of Austen, is a case in point. Her habit of heavily annotating with clippings from bookseller catalogs her copy of Keynes’s 1929 bibliography reveals that Austen’s best-known collector identified important books by using Keynes as a checklist against potential purchases. Tellingly, the greatest diversity among the books in her collection may be found among reprints published between 1930 and her death in 1975, years for which no bibliography yet existed to guide her.

Burke’s collection, in turn, played a role in shaping Gilson’s expanded bibliography, especially after the American bibliophile struck up a lasting friendship with the British scholar. Burke’s approach remains typical of most collectors, whether private or institutional, for bibliophiles and library curators alike rely on official scholarly bibliographies to identify what books they should purchase or preserve.

David Gilson’s own collection of Austen books, now at King’s College, Cambridge, reveals a startlingly different picture from that in his published bibliography. Karen Attar alone notices that “the view of books on the shelves makes immediately clear points about publishing trends which can be gained from a bibliography only by concentrated and focused searching.” Attar marvels that “most of the editions in the Gilson collection are, or were at their time of publication, cheap, meant to be accessible for the poorest people.”

From the author’s collection.

From the author’s collection.

It is therefore not the case that all cheap versions of Austen’s stories go unrecorded by Gilson only because his 1982 bibliography, submitted to the press in 1978, did not enjoy the benefit of online catalogs, image databases, or Internet commerce—although that is surely true for some missed copies. Few of his subsequent findings made it into the 1997 reprinting of his bibliography. For books at the bottom end of the market, his technical inventory and bibliographical language also remain quiet about publisher’s bindings or print runs. His book carries few images, and those few depict only major firsts.

My project is heavily illustrated because seeing the actual books is crucial to understanding both their intended audiences and Austen’s changing reputation. Attar, a curator of rare books, recognized only when looking at the physical books that Austen “is most startlingly an author of the people”; she saw that the many “cheap Victorian editions” owned by Gilson give the lie to Brian Southam’s assessment that during the Victorian era, “by the public at large, she was forgotten.”

Gilson and Southam formed part of a scholarly generation keen to cement the literary seriousness of Jane Austen. In his bibliography, Gilson sought to establish Austen’s canonicity by singling out certain editions for special notice, especially the well-produced books that conveyed a growing professional respect and investment in Austen: first reprinting, first illustrations, first translations, first luxury edition, and so forth. Other scholars, in turn, chose the editions worth studying or collecting by following his lead.

Scholarship has thus underemphasized Austen’s presence among the flotsam and jetsam of the 19th and 20th centuries’ cheapest books, since being popular among the rabble, as James observed, detracts from an author’s importance.

Although Gilson enlarged the inventory of known Austen editions, and the voracious Alberta Burke collected all manner of books postdating Keynes, Gilson’s bibliography is still far from an exhaustive record of Austen’s iterations in print. The order and discipline that bibliography brought to a chaotic landscape of books have masked Austen’s early diversity.

__________________________________

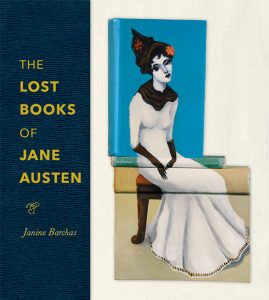

Excerpted from The Lost Books of Jane Austen. Used with the permission of the publisher, Johns Hopkins University Press. Copyright © 2019 by Janine Barchas.

Janine Barchas

Janine Barchas is the Louann and Larry Temple Centennial Professor of English Literature at the University of Texas at Austin. She is the author of Matters of Fact in Jane Austen: History, Location, and Celebrity and Graphic Design, Print Culture, and the Eighteenth-Century Novel. She is also the creator behind What Jane Saw (www.whatjanesaw.org).