Sometime in 1938, F. Scott Fitzgerald had an idea for a new novel. His last, Tender Is the Night, had been published in 1934 after he had worked on it for a decade, often under personal circumstances ranging from difficult to terrible. He had not been able to begin a next novel during the mid-1930s, and gave the reasons why very clearly in his “crack-up” essays, published in Esquire in February, March, and April 1936.

In the summer of 1937, Fitzgerald returned to Hollywood with a lucrative short-term contract from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, having previously failed in his attempts at screenwriting in 1927 and 1931. Hollywood was, as before, initially unhelpful to Fitzgerald’s creativity. He felt this keenly, complaining of it in letters and scattering the movie scripts he was doctoring with penciled interjections of disgust and boredom. His idea for the new novel was likely born of his initial frustration with the movies as well as the pressure Fitzgerald was placing upon himself to complete something substantive.

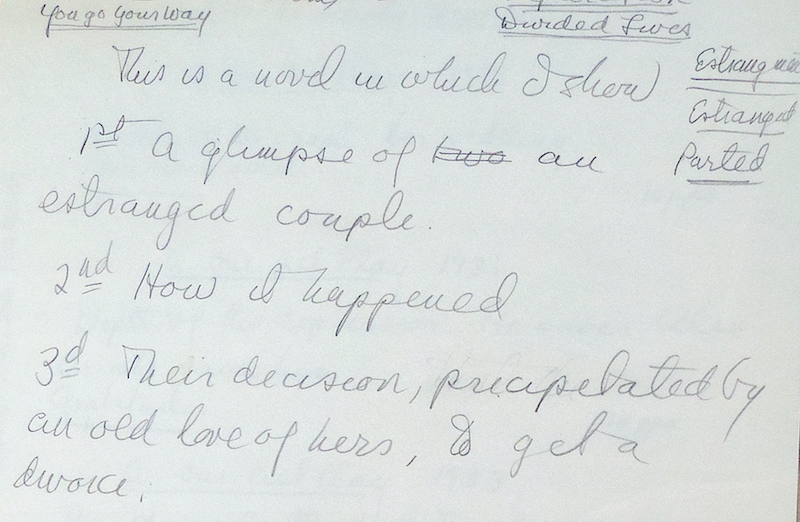

The outline is penciled on a single sheet in Fitzgerald’s hand. It has nothing directly to do with the rest of the archival material with which it is grouped, though it is on the same paper, and can be dated to the same time. The novel would have spanned the decade of the Great Depression, 1929-1938, and was to be based in the American history of those years. Fitzgerald outlined the heart of it in three phrases: “This is a novel in which I show 1st a glimpse of an estranged couple. 2nd how it happened. 3rd Their decision, precipitated by an old love of hers, to get a divorce.” Showing an estranged or even separated couple reconcile in the end is hardly new for Fitzgerald, but the context he suggests is fresh indeed. This one page reveals much about the thought process of a leading American writer in the very first stage of creative engagement with his material.

The ten years in question are crucial ones, covering the decade from the flash and crash of 1929 to the present at that time—and a personally difficult decade for Fitzgerald himself. After Zelda Fitzgerald’s first long hospitalization in 1930, the Fitzgeralds lived for only scattered months at a time as a couple again. Fitzgerald’s couple were to meet every year after their parting, against a backdrop of specific events Fitzgerald meant to emphasize or use as a thematic setting.

Here is his plan for the novel:

This is a novel in which I show

1st a glimpse of an estranged couple

2nd How it happened

3d Their decision, precipitated by an old love of hers, to get a divorce.

Courtesy of and © The Trustees of the Estate of F. Scott Fitzgerald

Courtesy of and © The Trustees of the Estate of F. Scott Fitzgerald

The theme is sketched thus: “Two people are estranged. Ten years pass and they forget + come together.” Fitzgerald also proposes a list of titles for his novel: Divorced, Separation, Estrangement, Estranged, Parted, You Go Your Way, and Divided Lives. Of these, You Go Your Way has the most in common with those of Fitzgerald’s other novels; he liked four-word titles.

This same-time-next-year story in ten chapters centers around critical historical events and manages a happy ending, even as the world slipped towards war once more—which Fitzgerald, like most people, sensed by 1938 was coming. He begins with American events that were also global disasters, and then begins to narrow his focus to the headlines of the East Coast, Chicago, and Los Angeles. “Boom” and “Depression” need no parsing or explanation. The last wild rush of stock speculation in 1929, ending with October’s Black Thursday crash, and the Depression following immediately thereafter resonated around the world.

For some brief shining moments in 1930, it looked as if America’s economy might recover. However, the increasing failures of banks both without and within the Federal Reserve system in late 1930 had a domino effect: the more banks found their cash reserves emptied, with insufficient funds to cover withdrawals, the more they failed. Of course people panicked and began withdrawing more money; in planning the novel, Fitzgerald selected “Panic” for 1931.

That Fitzgerald is interested in having his couple’s meeting involve the Panic echoes a theme he covered many other times, from The Great Gatsby to “Babylon Revisited” (1931) to the “Gwen” stories of the middle 1930s. He was always interested in the insecurity lurking within the wealthy classes, and particularly in the personal failings that could be so quickly revealed when wealth was acquired, or lost.

“Bonus march” refers to the sad “army” of the summer of 1932, when somewhere between 8,000 and 15,000 World War I veterans arrived in Washington, D.C. seeking immediate payment of the $1000 bonus each had received from Congress in 1924. The bonus certificates were meant to be redeemable in 1945, but the Depression had made many jobless and desperate for the money at once. Congress began to consider their request, and the Bonus Army built a camp in southeast Washington, on the flats of the Anacostia River and just across the river from Capitol Hill, while they waited. They called the camp Hooverville for the President who would not meet with them. The House of Representatives passed the “bonus bill” in mid-June, but, days later, the Senate rejected it.

President Hoover sent first the D.C. police, and then an army regiment commanded by General Douglas MacArthur, to force the Bonus Army, already decamping, to leave. Some of the men had brought families with them; newspaper reports savaged Hoover and the army for gassing and burning out the shanties and tents. The mayor of Johnstown, Pennsylvania, likening the disaster to the Johnstown Flood of 1890, welcomed refugees to town and paid to feed them himself, while Maud Edgell, a widow from Waterbury, Maryland, offered the men 25 acres of her own land for farms. One veteran killed by Washington police, William J. Hushka, was buried with military honors in Arlington National Cemetery. Hoover’s popularity, already sinking, crashed entirely, and he became a one-term President, winning only six states against Franklin D. Roosevelt that November.

Fitzgerald’s entry for the event of 1933 looks far cheerier: “Bank holiday.” It is not what it seems. In one of his first acts as President, FDR was obliged to close America’s banks in the wake of a spate of state bank closures. From February on, state governments had been declaring “bank holidays” and closing the doors to prevent “runs” on banks by panicked investors. By March, Congress was at work on the Emergency Banking Relief Act of 1933. After the act became law on March 9, the “holiday” ended with people returning their money to banks. FDR followed up by insisting the Senate take continued oversight of banking practices as part of the New Deal.

From this moment of rebuilding, Fitzgerald moves to a horrible tragedy. The S.S. Morro Castle was an ocean liner, the kind of ship Fitzgerald was fond of writing about in his stories, and had traveled on in his salad days during the 1920s when he, Zelda and their daughter Scottie went often between Europe and New York. A fierce nor’easter hit the Morro Castle on September 8, 1934, as she was headed home to Manhattan from Havana, and she caught fire—a fire that may have been set by one of the ship’s radio operators.

More than 500 people were on board, and everything that could go wrong did so. Fire alarms did not sound, the ship’s paint and wood made a swift inferno, no water came from the vessel’s fire hoses when they were turned on, and the storm at sea kept rescuers away and drowned those who did manage to get to the water. One hundred and thirty-seven passengers and crew members died just off the beaches of the New Jersey shore. Bodies washed up on the shore for days, and the burning wreck beached herself just off the end of Asbury Park’s Convention Hall pier. National newspapers ran accounts and photographs of the disaster and its aftermath for weeks; the cause of the fire was never officially determined.

Fitzgerald has added a line beneath Morro Castle, the name “Mrs. Simpson.” Bessie Wallis Warfield was a married Baltimore socialite who met Edward, Prince of Wales in early 1931. They soon began a well-publicized affair. Even Mrs. Simpson’s hometown paper, the Baltimore Sun, refused to be particularly coy about it, reporting in July 1934 that “Mrs. Simpson has a very smart position in British society and is in that clique called the ‘Prince of Wales’ set’ and is frequently invited to parties where His Royal Highness is the guest of honor.”

On January 10, 1936, Edward was crowned King Edward VIII, and on Nov. 16, when Mrs. Simpson’s decree nisi went through, Edward informed Prime Minister Baldwin, “I am going to marry Mrs. Simpson.” He first sent a proposal put to the Cabinet and the Dominion Prime Ministers that would permit Mrs. Simpson to become the King’s wife without the title of Queen. This was rejected, and Edward abdicated on Dec. 11. Two years later, Fitzgerald wrote a genial letter from Hollywood to his old friends Pete and Peggy Finney in Baltimore. Scottie Fitzgerald was sailing to New York on the S.S. Paris and, according to her father, had made a “speech on the boat . . . in which she won first prize for her state by praising Maryland as the home of the terrapin, horse racing and Mrs. Simpson.”

In March of 1935, lawyer and former special agent J. Edgar Hoover, head of the newly renamed Federal Bureau of Investigation, ordered an intense crackdown on “vice rackets,” Fitzgerald’s note for 1935. In the course of searching for hideouts and connections of John Dillinger, Charles Arthur “Pretty Boy” Floyd, the Barkers, and Charles “Lucky” Luciano, FBI agents found much collateral evidence used in 1935 and 1936 against rings of racketeers in varied illegal activities nationwide. Fitzgerald may also have had labor relations in mind, here; in May of 1935, the National Industrial Recovery Act, which specifically permitted workers to organize against their often racket-run employers, was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court.

Effectively repealed thus, it was replaced several months later by the far broader National Labor Relations Act, which permitted more legal action against organized crime. Yet in 1949, Malcolm Johnson of the New York Sun would win a Pulitzer Prize for reporting on the vice rackets still controlling the New York waterfront. Fitzgerald’s one-time collaborator Budd Schulberg based his celebrated On The Waterfront on Johnson’s stories.

“Flood” is the planned novel’s event for 1936. Sudden spring snowmelts and heavy rains in March hit New England and the mid-Atlantic simultaneously, and terrible floods coincided with St. Patrick’s Day. In Washington, D.C., the Navy Yards and airport both disappeared under the Potomac. Nearly 40 feet above its usual level, the Connecticut River filled downtown Hartford; more than 200 people were killed across New England. And Johnstown, Pennsylvania, in which more than 2,000 people had been killed when a dam burst in 1889, was ravaged again. That summer, FDR signed the first of a series of Flood Control Acts that Congress would pass for the next four years, providing for control measures and construction.

“Recovery Panay,” for the year 1937, refers to two things, I believe: the burst of economic recovery that occurred early in the year and the sinking of the U.S.S. Panay by Japan in December. Though American industrial production and wages rose that spring to their highest point during the Depression, the ensuing drop was swift, with unemployment rising frighteningly by autumn. The Panay incident of Dec. 12 was headline news and a major military and diplomatic incident. Japan had invaded China in the summer of 1937, and its army was outside the city of Nanking on December 11th. The Panay, in the Yangtze River to protect Standard Oil tankers, had evacuated Americans from the city on that day. Along with the tankers, the Panay was bombed from the air and sunk. Japan claimed not to have seen the American flags flying from the ships. However, the incident was filmed by two newsreel cameramen, and in 1938 Japan paid over $2 million in compensation.

“Recession Whitney,” the focus of Fitzgerald’s last chapter, encompasses the economic downturn after the early 1937 recovery. This depression-within-a-Depression continued until America entered World War II in December 1941. “Whitney” is both a cause and a symptom of the Depression. Richard Whitney, the Groton and Harvard-educated scion of an old Boston banking family, came to New York in 1910 and started his own bond brokerage business. His brother George prospered at Morgan Bank, and helped Richard to do so too with investments. However, Richard not only speculated and spent with both hands, but borrowed from George and Morgan, and embezzled from his own firm and from various New York Stock Exchange funds—accessible to him as he was the president of the NYSE during the 1930s.

On March 1, 1938, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that the Securities and Exchange Commission (created in 1934) was investigating Richard Whitney & Co. for “conduct apparently contrary to just and equitable principles of trade.” On the same day, Whitney & Co. declared itself insolvent. For stealing $105,000 from a trust fund set up by his father-in-law, and $109,000 from the New York Yacht Club, of which he was treasurer, Whitney was sentenced to five to 10 years in Sing Sing. He spent less than three years in prison, and was paroled to manage a family-owned dairy farm in Massachusetts.

Courtesy of and © The Trustees of the Estate of F. Scott Fitzgerald

Courtesy of and © The Trustees of the Estate of F. Scott Fitzgerald

How did Fitzgerald intend for his characters to be involved in these particular moments in history? Would FDR have been a central character, as he was in the history itself? Would Fitzgerald have written financiers, flood victims, soldiers, sailors, agents, politicians, society girls, shipwreck survivors, diplomats into the story? Zelda once wrote that Scott “always thought that [being a diplomat] was what he would most like to do, after writing and being a football hero.” How much agency, if any, would Fitzgerald’s couple have had in the face of these events, and how much involvement in, understanding of, or response to them? Would the “love plot” have shown people effectively caught in their own bubbles, immune to real world events—or paralyzed, perhaps infinitely altered, by them? Like all writers, and more so than many, Fitzgerald was interested in why things take the course they do, and how the past, and present events, shape outcomes.

Nothing that I have found, to date, suggests this idea for a novel went beyond its one-page plan. The details, though, show that Fitzgerald was far more deeply and intimately engaged with contemporary American history than anyone has thought. He was surrounded by the day’s news every morning, steeped in it. This should hardly be a surprise; critics, most recently Sarah Churchwell, in Careless People (2013), have shown how Fitzgerald was a sponge for newspaper and magazine stories that he worked into his fiction. His clippings files at Princeton show what he saved and found interesting and scribbled notes upon—everything from stories about Sonja Henie ice-skating to flower gardens to what the Pope was doing in 1933.

You Go Your Way would have been difficult to write as it is outlined, but Fitzgerald’s ambition in doing so and beginning to wrestle with it is grand to see.You Go Your Way and Divided Lives are most interesting as potential titles for such a novel because both offer options for independence, possibilities of going against the current of a relationship—and perhaps history—rather than merely with that current. A short story of 1937, “Offside Play,” circles around these ideas; in that case, the extent to which the love plot is ordained, or a loss of individual action or choice, rather than, as it may seem, decisive action.

What is clear from the skeleton of You Go Your Way is, first, Fitzgerald’s intense and detailed engagement in, and knowledge of, critical moments in American history throughout the 1930s. His creative imagination often focused on his own recent past; here, Fitzgerald is spreading his mental net wider, and thinking about the country and its chief recent crises. Fitzgerald also intended to give the book something none of his other novels had had: a happy ending. “They forget + come together.” The problems of two little people don’t amount to much against the backdrop of a world in terrible trouble, heading once more to battle. In the end, his nameless couple would forget their differences and reunite in the horrible face of an approaching world war. This seems less like romantic wish-fulfillment than a demonstration of how puny human passions and disagreements are, in relation to the big forces of history. 1938 was, after all, the year of the fall of Czechoslovakia, the opening of the first concentration camps, and Kristallnacht. The invasion of Poland in September 1939 confirmed a war that had already begun.

When he came to Hollywood in July of 1937, Fitzgerald did not think he would stay in Los Angeles after his first MGM contract ended. He wanted to be either in Baltimore or, preferably, New York. However, a year later, many things had changed. He had met and fallen in love with the Hollywood gossip columnist Sheilah Graham, and was living with her that summer in a cottage in Malibu: infidelity made reality, coloring both his work on screenplays, and the novel plan. Indeed, he was working during early 1938 on an original screenplay, “Infidelity,” designed for Joan Crawford, which was scrapped by midyear. After having initially wasted time, in his words, “fixing up leprous stories” Fitzgerald got some good jobs, working on Madame Curie and Gone With The Wind, for which he made some significant dialogue changes.

As Fitzgerald became more at home in Hollywood, he began writing fiction based in his present setting, circumstances, and experiences. A series of stories about an alcoholic, failed Irish-American screenwriter named Pat Hobby inspired him through 1939, and then gave way to a new novel about a producer named Monroe Stahr, and his phantom and present loves—the personal life, in some ways, that Fitzgerald was living by then between Sheilah and Zelda, who he would never divorce, or stop loving. This novel he began in autumn 1939, and eventually called “The Love of the Last Tycoon: A Western.” His idea for a novel that would at once chronicle and quit the decade of the Great Depression, as his earlier novels had done for the Jazz Age, and serve up a happy ending in which an estranged couple reunite, no longer suited Fitzgerald by 1939.

You Go Your Way would have been difficult to write as it is sketched, but Fitzgerald’s ambition in doing so and beginning to wrestle with it, in the wonderfully difficult straightjacket of the year-by-year structure, is grand to see. Knowing about this idea for a novel also informs the one that superseded it and became The Last Tycoon. The plot of what exists of The Last Tycoon—lovers with no real grasp of their own lives, let alone of American culture’s forces—gains an edge in the light of Fitzgerald’s earlier, abandoned outline.

Research materials copyright & courtesy of The Trustees of the Fitzgerald Estate and Princeton University Library.