The New Losers of Lit: A Reading List

The Days of the Rich, White, Male Failure Are on the Wane

Once upon a time, the literary loser was a straight white man with access to the best life could offer—and yet he managed to screw it all up anyway. From Chaucer’s drunken cuckold the Miller, to George Gissing’s hipster hack Milvain, and on to Roddy Doyle’s feckless impresario Jimmy Rabbitte, Western fiction has long cherished losers.

Until quite recently, “loser lit” has meant not tragedy, not sadness, not accidents of fate, but quite specifically self-driven failure, the sort of slipping down that only looks funny when done with an Ivy League degree and lost family money. No one laughs when a person who couldn’t possibly aim for more fails—we prefer our cruelty cloaked in camel hair. The anti-heroes of 20th-century loser lit were born of the post-World War II Western zeitgeist in which social class, race divisions, gender, and sexual orientation supported the well-educated, well-monied, straight white male.

But somewhere in the late 20th century, as those white-male losers gleefully shagged and smoked and drank their way to the brink, our ideas of success (and the concomitant failure that defines the contemporary loser lit character) took on different forms, and a new loser emerged. These literary failures aren’t all seeking the CEO chair, the best academic appointment, or even artistic recognition: sometimes they just want to be seen by someone they love, or survive an apocalypse, or make it out of a dysfunctional family. The fact that authors can now turn those desires into the stuff of comic fiction says a great deal about how far we’ve come in terms of defining the brass ring.

In order to be true “loser lit,” a book has to set a standard of achievement the protagonist cannot attain (if everyone’s flailing and living in their parents’ basement, who cares?). That may be why Canadian Miriam Toews’s The Flying Troutmans signaled a new season for loser lit, one in which adolescent characters like her 11-year-old Thebes could simultaneously seek some sort of future and detail the fuck-ups of an older sibling (or aunt, or stepmother, or any relative, really) as the de facto adult attempts to keep a ragtag group of idiosyncratic friends and family members from penury and disintegration.

Toews makes me think of Lydia Millet, whose entire oeuvre might be said to concern new losers—but whose recent Mermaids in Paradise definitely does, telling the story of a pair of newlywed losers whose fascination with the titular mythic creatures derails their “real” lives. Meanwhile, everyone’s favorite brand of Italian bitters, Elena Ferrante, shows that no matter how and why people are successful, they’ll throw themselves against the bars of their cages if it means inching ahead of a rival.

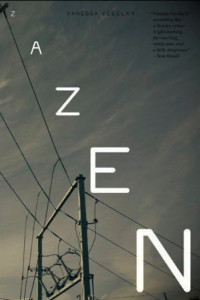

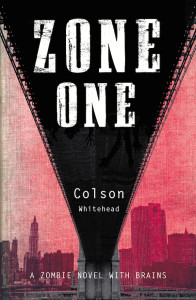

Ferrante forms a perfect pivot, because although her novels have appeared on the U.S. stage fairly recently, they concern women of a certain age, women who would have written their own “loser lit” when younger if their cultural origins had allowed them to—and so Ferrante’s books are front-and-center on shelves alongside the work of younger writers. The newest losers of literature include Gary Shteyngart’s Lenny Abramov in Super Sad True Love Story, Mark Spitz of Colson Whitehead’s Zone One, Susan Choi’s Regina in My Education, and Vanessa Veselka’s Della in Zazen, and each of these shows a loser whose decisions are complicated not simply by anger and frustration, but by the effects outer events have on their inner turmoil.

Whether it’s a dystopian Manhattan (Shteyngart), zombie war (Whitehead), complicated love triangle (Choi), or post-apocalyptic Pacific Northwest (Veselka), the new losers are searching for ways to integrate their acknowledged flaws and myriad setbacks with some sort of way forward. Although some of the classics of earlier loser lit tend in this direction, what makes these characters different is a combination of background and perspective. Rakesh Satyal’s Blue Boy is South Asian, and in Woke up Lonely by Fiona Maazel, Esme’s ex-husband is the leader of a cult.

The world is more diverse than it once was: A bisexual aspiring academic can mess up her life as easily as can a disenfranchised vegan restaurant chef. And we’re paying attention to more than just one path: Success doesn’t always mean a job with promotion possibilities, but could mean finding a safe place to live, a person to love, or even the elusive concept of inner peace. In Caitlin Moran’s How to Build a Girl, just enough money to escape home is the prize; in Hope: A Tragedy by Shalom Auslander, ridding a home of a ghost is the protagonist’s goal.

The fact is, inner turmoil of the sort experienced by the newest crop of loser lit novelists makes for a more complex, interesting reading experience than the previous conceit of “jerk gets his, in the end.” It might be best embodied by one of my favorite loser protagonists of 2014, Pasha Nasmertov of Panic in a Suitcase by Yelena Akhtiorskaya (“the first great novel of Brighton Beach”). Of Pasha, the narrator says: “[his] talent was to shift dynamics until all sympathy was directed toward him… He aroused feelings without necessarily returning them and was permanently enclosed in an aura of exemption.” This, then, is what “loser lit,” past and present, is really about: A person who chooses manipulation over engagement and attention over action. For those of us who enjoy these books, that’s good news: We won’t run out of loser protagonists as long as there are humans—of all different genders, races, creeds, and classes—bumbling and stumbling about the earth.

READING LIST SLIDESHOW: The New Losers of Lit

- Satyal’s take on the picaresque threatens to become burlesque when his young hero Kiran Sharma, who loves ballet and mom’s kohl, decides to reveal at a school talent show that he’s actually the reincarnation of Krishnaji—but a light dusting of magical realism helps it turn into a new consideration of how we look at skin color.

- Moving is stressful for anyone, but if you’re would-be upstate farmer Solomon Kugel and your new house has an attic inhabited by Anne Frank, it moves from high-blood pressure to Richter Scale territory. Auslander’s Anne Frank, crabbed with age and devoted to her noisy typewriter, is a feat of imagination—and, perhaps, optimism.

- Johanna Morrigan, 14 and seemingly trapped in poverty on a British housing estate, decides to “build” herself from scratch as Dolly Wilde, a Lady Sex Adventurer who writes precocious music reviews for a newspaper (it’s 1990, after all). When she whacks up against her own limits, she reconsiders the brass ring she’s been chasing.

- Some critics have called this “The first great novel of Brighton Beach,” which is almost the same as providing a sticker reading “The New Loser Lit.” You’ll understand once you meet the Nasmertov family, recently arrived from Odessa to America, and completely confused about how to get ahead without falling behind.

- Lenny Abramov faces a near (“Let’s say next Tuesday”) dystopian Manhattan with little save his bald spot and library of so-last-century paper books. His brave new world, including credit-based riots, is upended by love in the form of Korean-American Eunice Park, not so sure about her “ancient dork” of a boyfriend.

- Forget “Little Miss Sunshine;” siblings Logan and Thebes Troutman, along with their Aunt Hattie are the people on a cross-country van trip you want to follow. They’re darker, richer, and deeper than any film characters, and their bonding will move you past tears as they head towards South Dakota in search of a father figure.

- Esme Haas never meant to become the agent assigned to track her ex-husband Thurlow Dan, the leader of a group called The Helix. Dan’s movement fights solitude, which he conflates with loneliness—and slowly, Esme and her gang of misfit spies realize that creating community has more to do with character than cult.

- Della Mylinek lives and works in a city under siege, which many inhabitants respond to with a combination of ennui, rage, and superficial rebellion (sex parties, hair dying); for her and those around her, “alternative lifestyle” is the only alternative. But a new version of success opens up as Della dreams of escape—and doesn’t.