The Necessity (and Inadequacy) of Trans Self-Acceptance Narratives

Isle McElroy on Torrey Peters, Veronica Esposito, and the Divide Between Being and Doing Trans

I planned to write one of those essays my mom would share with her friends on Facebook. In this essay, shame and doubt would crack like caked mud to reveal the self-love that had always been hiding beneath. In this essay, an overlooked small press chapbook by an author I admire would help me accept myself as a trans person. This book would welcome me into myself. But as I sat down to write, in May 2021, something started to happen—rather, something was reinvigorated, for what started happening had been happening for generations—and writing a self-acceptance essay seemed frivolous. Bills began emerging in largely conservative states that would severely restrict the rights of trans people, especially trans children.

These were far from the first bills directed against trans people. The first anti-trans legislation arrived in the US before the US existed: Susan Stryker points out in her book Transgender History that Massachusetts passed its first laws against “crossdressing” in the 1690s. Similar laws started appearing in American cities around the 1850s, and beginning late in the 20th century, transsexualism was psychopathologized as GID, Gender Identity Disorder. The medicalization of transness did help some people gain access to medical intervention, but the majority of those to whom the terms applied, Stryker notes, “resented having their sense of gender labeled as a sickness and their identities classified as disordered.” Stryker’s book makes clear that the bills being proposed today are part of an ongoing effort by the state to criminalize being trans. The problem with these laws—beyond their obvious cruelty, their infringement on human rights—is that even as the lawmakers who write them attempt to legislate trans people out of existence, trans people do, as Oreo recently pointed out, “exist.”

One way to make sense of trans’ people’s response to these bills is to look at the divide between Being Trans and Doing Trans as recently depicted in Torrey Peters’s excellent novel, Detransition, Baby. Through the character of Ames, who has recently detransitioned, Peters suggests that trans people, no matter how they present, are trans (being trans); it is coming out and entering society as a trans person—facing personal, emotional, and legislative hurdles—that constitutes doing trans. Though Ames no longer does trans, he still is trans. These bills might prevent people from doing trans, but they cannot prevent us from being trans.

This language is also important for understanding why Veronica Esposito’s 2016 memoir, The Surrender, resonated so deeply with me before I came out. The book charts Esposito’s gradual acceptance of both being and doing trans. It opens during “a time of great indulgence” after Esposito has purchased a wig in order to feel “hair brushing the small of [her] back.” The wig is a final addition to her new look: the new dress, rich plum lipstick, eyeshadow, tights, and four-inch heels, all impulsive purchases. For months, she has found her reflection “almost entirely satisfying.” The wig is not merely an accessory; it is an integral part of her self-realization, the piece that will, temporarily, help her feel whole.

These bills might prevent people from doing trans, but they cannot prevent us from being trans.

Throughout the opening pages, Esposito weaves thrillingly between desire and doubt. “There would be no more restraint,” she writes; she will “answer all impulses without hesitation.” These pages are guided by feelings of shame and longing and freedom, all the feelings that are attached to her new collection of clothing. This is not her first purchasing binge; in the past, she heaved her new clothes in the trash in fits of despair and embarrassment. This time, she promises to keep the clothing and makeup and wig, to protect this person she wishes to become.

I first read The Surrender before it became The Surrender. In 2014, Esposito published an essay called “The Last Redoubt” in The White Review that is, on its surface, about the film Close-Up by the Iranian director Abbos Kiarostami. I had loved the film, a sly story of imitation and fraud based on a real-life case of identity theft. Rather than cast actors, Kiarostami cast the very people involved in the fraud, including the perpetrator, the victims, and the judge who adjudicated the case. I had respected Esposito’s criticism for years, especially her literary blog Conversational Reading. When I read “The Last Redoubt,” I discovered she and I had far more in common than our love for the films of Kiarostami.

The first dress I wore was a frilly pink tutu hauled out of a plastic bin in my preschool playroom. Me and another boy traded off with the tutu until we were encouraged to put it away. The second dress belonged to my stepsisters. At my father’s house one weekend, I asked the two of them—four and six years older than me—to dress me up like a girl. They presented me to my father, who demanded to know why they’d done this to me. “He asked us to,” they told him.

Nearly ten years would elapse before I wore my next dress, this time in the attic of my childhood home. The dress belonged to my mom, and I might have continued wearing it if she hadn’t unearthed an email correspondence I had had with a trans person I’d met on the internet. I never spoke to the trans person again. It was 2002, and there were few things scarier for parents at the time than the people their children met on the internet. My women’s clothes were cinched into a Hefty bag and dragged to the end of the driveway. I convinced myself—and my parents—that that part of my life was behind me, a passing spell of the youthful impulse to pretend I was someone I wasn’t.

In the essay, Esposito uses Close-Up to assess larger questions of identity and performance. Specifically, she draws a parallel between Sabzian—a man who defrauds a wealthy family by impersonating the famous film director Mohsen Makhmalbaf—and herself, as she comes to terms with her trans identity and learns to give space to “this screaming-baby-like thing fighting for its share of my body.” Esposito’s essay is not a manifesto for self-love; instead, it captures the fits and starts of identity construction, the utter terror of becoming yourself—especially if that self has been marginalized, derided, or legislated against. “I cannot remember a point when I ever believed in what I see” in the mirror, she tells us. Without the dress, the wig, the lipstick, the person in the mirror is a lie—and for this reason, she sympathizes with Sabzian, who, at the end of Close-Up, confesses to a judge and his victims that he impersonated Makhmalbaf out of a desire to escape his own suffering.

I read this essay when I was living with my future wife, a cis woman, and though we had briefly discussed what I nervously dismissed as a fetish for crossdressing—a false reassurance that Esposito also gives to a live-in partner—I was years away from accepting myself as trans. Like Esposito, I was drawn to the safety of parallels and abstractions, reflections and refractions, instead of engaging, seriously, with my true self. Most importantly, “The Last Redoubt” made clear that my teenage self had not just been working through a phase.

The essay changed little in my day-to-day life. I remember excitedly recommending it to my partner. She didn’t read it, or if she did, she didn’t discuss it with me. I was, in some ways, relieved by this. I thought about the essay often, though, drawn to its mix of confession and evasion. I saw in the piece my own dueling impulses to lean into myself and to sprint back away. Two years later, Esposito published The Surrender. I ordered a signed physical copy and, when it arrived, I slid the small burgundy book out of its envelope and into my desk, where it hid for months, until my wife went away for a six-week writing retreat.

When I finally read the opening pages of The Surrender, safely alone on my couch, it felt like stepping inside my own mind. Esposito’s doubt, ambivalence, shame, desire, and impulsive lunges toward selfhood gave language to 28 years of feelings I had never been able to name. I was still two years away from buying my first wig—a wavy shoulder-length thing that cost less than a cocktail—but I understood the inadequacy of mirrors. I had my own baby-like thing inside me, fighting for its share of my body.

I was drawn to the safety of parallels and abstractions, reflections and refractions, instead of engaging, seriously, with my true self.

Esposito’s memoir lacks the assuredness of a memoir like Juliet Jacques’s Trans and doesn’t aspire to the tenderness and wit of Casey Plett’s short story collection A Safe Girl to Love. The Surrender, however, captures what those books do not: the sticky ambivalence of living with an ongoing decision that appears to have no end. Though both Jacques and Plett acknowledge this particular ambivalence, they seem more distant from it, as though it’s a field they have driven by on the highway. Esposito writes from that field. And I read it from that same field, a few hundred paces behind her.

Before reading The Surrender, I naively assumed other trans people just knew they were trans, that every pluck of doubt inside me proved I was stolidly cis. But Esposito’s embrace of her doubt and discouragement, her patterns of bingeing on clothes and discarding them, her impulse to cloak her feelings behind elusions and allusions, spoke more clearly to me than any other book I had read by a trans author. Nearly four years after first reading The Surrender, I am only just leaving that field, only beginning to embrace being trans and the world I have entered.

I feel cynical about writing a self-acceptance essay while lawmakers continue to legalize discrimination against trans children. The recent bills in Virginia, Florida, North Dakota, and elsewhere are merely addendums to centuries of normalized discrimination against trans people, who face mounting challenges in obtaining healthcare, housing, jobs, and safe relationships. Murders of transgender people continue to rise annually in the US. Confronted with massive structural impediments, declarations of self-acceptance and visibility risk coming off as cheap neoliberal antics, fig leaves concealing a patriarchal society’s true feelings about trans people: it would prefer if we didn’t exist.

Is a self-acceptance essay enough to convince that very same society that trans people should exist? It isn’t. The Surrender did not eliminate my feelings of doubt and self-loathing and shame. The book made nothing easier for me; it did little to prepare me for the difficulty of coming out. The Surrender wasn’t enough. Detransition, Baby wasn’t enough. Trans wasn’t enough. A Safe Girl to Love wasn’t enough. Confessions of the Fox wasn’t enough. Transgender History wasn’t enough. Time is the Thing a Body Moves Through wasn’t enough. Reverse Cowgirl wasn’t enough. A Year Without a Name wasn’t enough. Something That May Shock and Discredit You wasn’t enough. She’s Not There wasn’t enough. This essay isn’t enough. I love these books. They helped keep me alive. But perhaps someday there won’t be anything unusual or revelatory about them. They will merely be books about people.

______________________________________________

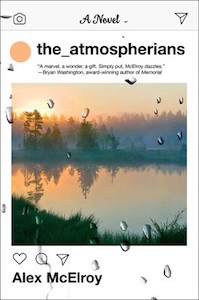

Alex McElroy’s novel The Atmospherians is available now via Atria Books.

Isle McElroy

Isle McElroy (they/them) is a non-binary author based in New York. Their writing has appeared in the New York Times, The Atlantic, New York Times Magazine, The Cut, GQ, The Guardian, Vogue, Bon Appétit, and other publications. They have received fellowships from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Tin House Summer Workshop, the Sewanee Writers Conference, and they were named one of The Strand's 30 Writers to Watch. In May 2021, Isle founded Debuts & Redos, a reading series for authors who published books during the pandemic. Their first novel, The Atmospherians, was named an Editor's Choice by the New York Times and a book of the year by Esquire, Electric Literature, Debutiful, and many other outlets.