The Myth of True Love Hurts Us All—Especially Women

Jen Winston on the True Love Industrial Complex and the Rejuvenating Power of Queerness

It’s not very 2021/yes bitch!/you do you to end this book with a love story. For starters, love is often happy, and happiness, as they say, does not stain the page. Yes, it’s important (radical even!) to see people of all identities experiencing joy, but unless you’re talking about that blissed-out roller skater on Instagram, watching someone else share their contentment kind of blows. Audiences are looking for drama! Conflict! Pain! The hero should be tormented by a longing, a want—that way, the audience can root for them to achieve it (spoiler for every piece of media ever: They will achieve it, but not in the way they expected!).

While heroes often do seek out love itself, the juiciest parts of those stories will always be the chase. Resolutions masquerade as critical plot points but they’re usually preordained throwaways, driveways that we already know we’re going to pull into. It’s why so many rom-coms put the much-anticipated kiss right before the credits: No one wants to see the protagonists cook a healthy dinner and go to bed by nine.

To craft an exciting love story, the goal must remain just out of reach at all times. Maybe that’s why many adults wander the earth like kids who still believe in Santa, searching for True Love, not realizing that the idea is faker than Hilaria Baldwin’s accent. I didn’t find this out until I was twenty, and only because I was enrolled in an elective called the Philosophy of Love. Every week, the professor showed us how the romantic sausage got made, taking us through marriage’s economic origins, Aristophanes’s “two halves,” and the poetic bigotry of Don Draper. We read Tristan and Iseult, Plato, and Kierkegaard, charting the centuries-long dawn of a concept that still rules our day-to-day.

Naturally, the only reason I paid attention in this class was to make one of my friends fall in love with me: a creative writing major with extremely flat feet who always had his nose in a book. One day he said my syllabus looked “neat” (he wasn’t being sarcastic—that was just how he talked), and before I knew it, I’d finished every reading. At the end of the class, I asked the TA if he’d write me a letter of recommendation to apply for a philosophy PhD. (He said no and I was fine with that—I never picked up a philosophy book again.)

After I understood basic feminism (which I credit entirely to a rousing listen of P!nk’s M!ssundaztood), I realized how deeply the idea of True Love had manipulated me. For women, the indoctrination starts early and never lets up—one minute we’re watching Sleeping Beauty, the next we’ve finished nineteen seasons of Say Yes to the Dress. The True Love industrial complex feeds us grandiose dreams to occupy our dainty brains, hopeful that wedding planning will distract from thoughts of uprising and masturbation.

One of True Love’s cruelest jokes is that the entire concept hinges on scarcity. According to season one of Emily in Paris, a Netflix show that I definitely did not watch, the defining characteristic of “the one” is someone who exists in close quarters but remains perpetually out of reach. According to more scholarly sources like Sex and the City, “the one” can only be in every fifth episode (you’ll know him when he does show up because he’ll stare at you like he forgot your name). A helpful way to cut through the bullshit is to ask yourself who the characters would be in real life and my favorite method to do this consists of imagining who they would’ve voted for in the 2020 U.S. elections. In SATC’s case, it would’ve played out as follows:

Carrie: Campaigned for Mayor Pete in the primary, then bubbled in Biden but forgot to mail in her absentee ballot

Charlotte: Voted Trump in 2016 but 2020’s BLM protests persuaded her to go blue (also probably shared several infographics to her Instagram story with the caption “now more than ever”)

Samantha: Biden, but only because she had terrible sex with Melania Trump in college

Miranda: Bernie in the primary, then Biden on New York’s Working Families Party line

Steve: Same as Miranda but also volunteered as a poll worker

Big: Trump

As Big himself embodies, True Love is nothing without capitalist markers of success. Cognitively, the connection begins with gifts—we’ve been programmed to think that an $18.99 drugstore bouquet of roses on Valentine’s Day means something, while the absence of those roses warrants spiraling out and second-guessing every emoji we’ve ever sent. Romance and capitalism are so enmeshed that our aspirations of love often include aspirations of money. Focus Features even marketed Fifty Shades of Grey with a digital tour of Christian’s penthouse apartment, proving that the fantasy was as much about being rich as it was about BDSM.

Why was I so willing to discard myself? You guessed it: because I wanted True Love, and I didn’t care if that love was fake as fuck.

As icing on the proverbial wedding cake of horrors, the concept of True Love has always been heteronormative. That said, it’s important to note this flawed ideology isn’t just reserved for straight people—it’s equal opportunity bullshit, happy to ruin your life no matter how you identify. Anyone of any gender can blame True Love if they care more about being in “a relationship” than they care about the person they’re in said relationship with.

While the myth of True Love hurts everyone, it’s patriarchal in nature, meaning it comes for women and femmes especially hard. On top of all the other nonsense we’re supposed to live up to, we’re also supposed to become “the perfect wife.”

I’ve said “I love you” to four men throughout my life, but every time I uttered those words, I wondered if I was lying. In each relationship I had the nagging sense that I’d compromised myself, and that I’d done so because I was desperate for a storybook romance. At the time I sincerely believed that staying silent about my needs and regularly shaving my legs were necessary investments in “us.”

But in each case, I could never maintain this illusion for long. I usually blew my cover with something hygiene-related (e.g., disposable contacts I’d left on their floor), but by the time those slipups happened I’d already been stifling myself for months. For example: My love language is Words of Affirmation, and I feel most cared for when my partner showers me with compliments. But instead of voicing that to my boyfriends (which would’ve set both of us up for success), I simply contorted my personality into something I thought they *might* compliment: an amalgamation of their interests, passions, and visions of “the perfect girl.” I listened to Bill Simmons’s podcast. I took a Skillshare course on cryptocurrency. I left my own calendar for dead in an effort to center their volatile schedules, once bailing on a friend’s birthday because Ian was in town and wanted to watch Westworld. (He fell asleep halfway through.)

Why was I so willing to discard myself? You guessed it: because I wanted True Love, and I didn’t care if that love was fake as fuck. It’s hard to admit but I clung to the hope that one of these dudes would give me jewelry, chocolate, or—best case—a proposal. I didn’t have a Pinterest board (not a public one, anyway) but that didn’t stop me from fantasizing. (The ceremony begins at sunset in a Neukölln courtyard—I step out in a red jumpsuit wearing a graphic Euphoria eye, and the crowd goes wild.)

In hindsight, all my love stories with men had only been performances—one-woman shows furthering the True Love agenda, perpetuating the harmful idea that a woman’s sole purpose is to provide sex and free therapy to her husband until one of them dies. Sure, a feminist can still “fall in love,” but she should do it only if it’s what she wants. But where’s the line? There’s things we want, and then there’s things the world tells us to want. But how can we determine where one ends and the other begins?

If I’d “fallen in love” with a cis man, I’d probably still be out there squashing myself. This book’s ending would consist of sugarcoated essays that spoke to his strengths, concluding with a chapter called “Actually, Not All Men! Who Knew?” A close reading would indicate severe gaslighting on both the guy’s part and the patriarchy’s, but since I’d failed to “hold myself accountable” and call this out, Empowerment Instagram would deplatform me immediately (rightfully so).

When I say Queer Love, I mean love that makes its own rules.

This isn’t to say that healthy relationships with cis men cannot exist—just that it seems like they cannot exist for me. Thanks to heaps of internalized misogyny, I tend to make myself smaller—I abide by traditional gender roles until a hip queer person on the internet tells me it’s time to stop. Fortunately the hip queers are usually right—and since systemic sexism has impacted far more lives than just mine, I bet I’m not alone.

But luckily for me (and for you, dear reader, since you are somehow still here), my love story isn’t about True Love. It’s about Queer Love. And that one, I didn’t study in school.

Queer Love, it turns out, is everything True Love wishes it could be, and the same goes for Queer Love stories—they’re the best kind of love stories because they’re forced to self-determine, which means they do their own world- building (Lord of the Rings, but make it gay . . . er than it already is). David Halperin writes, “Love has seemed too intimately bound up with institutions and discourses of the ‘normal,’ too deeply embedded in standard narratives of romance, to be available for ‘queering.’” Queer Love then requires us to create something entirely new—it must be different than the heteronormative, patriarchal tropes from whence we came.

Before I go any further with this and wake the “BuT WhAt AbOuT sTrAiGhT pRiDe” crowd, I should clarify: You don’t have to be an LGBTQ+ person to experience Queer Love. The only thing queer love requires is authenticity, and you can have that no matter who your partner(s) is/are. You can also lack it—being queer doesn’t inherently make you down-to-earth (see: Jeffree Star, Rachel Dolezal, or Ursula in The Little Mermaid). I’m no authenticity role model either: I’ve been bisexual my whole life, thus all of my relationships with men were *technically* queer relationships. But was I honest? Did I show up with my full self? The tattoo I got to impress a high school crush says no. (Actually it says “this too shall pass” and I’m in the process of getting it removed.)

People tend to focus on the practical appeal of queer relationships—plenty of think pieces have celebrated these bonds for the way they transcend gender roles. When sexism doesn’t tell you who should cook, who cooks? The better cook. Beautiful.

But as I said, a Queer Love story isn’t just a straight love story featuring queer people—it’s about a love that is rooted in radical, asymmetrical truth. Queer Love is inherently political—an action that bell hooks defined as “the practice of freedom.” Queer Love takes up space—it is earth-shattering and expansive, yet somehow remains vulnerable even in its strongest form.

When I say Queer Love, I don’t mean love in a legal sense. I don’t mean domestic partnerships, divorces, or whatever it’s called when two white gays start a joint TikTok account.

When I say Queer Love, I mean love that makes its own rules. Love that exists without borders and thrives without clean lines. Love that creates more space than it takes up.

So yes—this book ends with a Queer Love story, and that story happens to involve two queer people. Sometimes I wonder if my partner and I were drawn to each other because we both struggle with binaries, each of us viewing the world as overlapping Venn diagrams where everything happens to be something else too. Maybe we shared an intuitive understanding about the power in shades of gray.

Or maybe, like a ditzy girl in a rom-com, I just happened to get lost in their eyes.

___________________________________________________

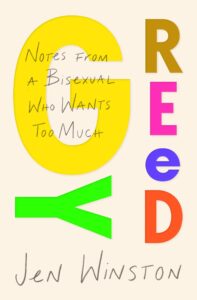

Copyright © 2021 by Jen Winston. From GREEDY: Notes from a Bisexual Who Wants Too Much by Jen Winston. Reprinted by permission of Atria Books, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Jen Winston

Jen Winston (she/they) is a writer, creative director, and bisexual based in Brooklyn. Their work bridges the intersection of sex, politics, and technology, and has been featured in The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, CNN, and more. Jen is passionate about unlearning and creating work that helps others do the same. Her newsletter, The Bi Monthly, is dedicated to exploring bi issues and experiences—it comes out every month, much like Jen herself. Follow Jen on Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok (please, she’s begging you): @Jenerous.