The Me in the Screen: Steffan Triplett on Doppelgängers and Doubles, in Horror and Queer Life

“A queer person is used to keeping secrets, telling lies, sectioning off parts of themselves.”

My semester abroad was the first time I had sex with someone who wasn’t already my boyfriend. I’d planned for this to happen, even though it was something that, before, I’d told myself I wasn’t planning on. I’d convinced myself it was something that I wouldn’t do or that I was uninterested in. It was 2013, and I was 20 years old, still shaking off the rhetorical and emotional baggage that came with a southwestern Missouri upbringing, tinged with morality and religion, the abstinence-only sex education carved into my memory of middle school.

I was still fearful of sexuality, even by association: when my father brought me to the airport, I panicked that the small box of condoms I’d put in my carry-on would sound off an alarm, alerting everyone that I was sexually active. So I took my bag in the bathroom and switched the box into the suitcase that I was checking. When I brought it back out, my father, unhappy with how we’d packed things earlier, insisted on rearranging them. He unzipped the suitcase and saw the box.

“What’s this?” he said as he was opening it.

I froze. A moment passed as he glanced at its contents. He closed it and we never spoke anymore about it. I was horrified. These were all free condoms I’d amassed that year as a college student at various on-campus events, though I told myself I wasn’t actually planning on ever using them anyway.

And yet, I spent many nights in Madrid kissing men in clubs and following them back to their apartments. It was easier than I expected, both to do away with my previous inhibitions, and also to catalog what then felt to me like pleasurable transgressions. I kept a list of names of men I’d hooked up with. It quickly grew larger than the list I’d kept in my non-abroad life, and with each addition to that list, I left the old me in the US, giving myself permission to deny my current reality. This type of sexual freedom didn’t fit with the more respectable self-image I’d crafted in my head. This version of myself did not, and would not, exist back home. None of this counts, I told myself. None of this is real.

*

The first scene in Jordan Peele’s Us is a scene about misinterpretation. The camera slowly zooms toward a television set as commercials roll on an ordinary evening. We’re not just watching a local broadcast near Santa Cruz in 1986, we’re actually watching someone else watch it; she’s a little girl—you can make her out in the TV reflection, wearing a blue top with ruffles and white piping, rapt, alone in the living room. You can see her in the black of the blank air space between commercials.

The focus here seems to be on the commercial, but it’s really on the screen, on the girl watching it. We notice her after the fact; notice her noticing the Hands Across America event happening that summer—a human chain connecting American citizens from one coast to another. It was a strange (real-world) fundraising attempt to fight homelessness and hunger, touting a narrative about connection, how we’re all the same and might band together to fix the world’s problems. The girl is taken with this idea. It will drive her later on, becoming the visual basis for the statement she will make years later after being stuck underground in a life she never asked for.

The little girl is one of the film’s protagonists, but not the one the audience expects. Us is really a film about two versions of her. There’s the young Adelaide we watch watching the television. On a family trip to the carnival on the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk, that Adelaide encounters another version of herself in a hall of mirrors.

If there’s a double in literature or film, there’s always the threat that they’ll take the other’s place.

Unknown to the audience, Adelaide’s double switches places with her and takes over her life. The adult Adelaide we follow across the film, now married to her husband Gabe Wilson and mother to two kids, is not the same Adelaide as before—that one is now going by “Red” (both are portrayed by Lupita Nyong’o). Thus, much of one’s initial viewing of Us is a misperception too. We spend the whole first viewing of the film thinking we’re watching one life when it’s really been someone else’s. At the film’s end, “Adelaide” kills her double, yes, but in “reality,” Adelaide destroys herself.

*

If there’s a double in literature or film, there’s always the threat that they’ll take the other’s place. I’ve watched enough seasons of The Vampire Diaries and plenty of late-night horror and science-fiction films to know as much. More unsettlingly, during my semester abroad in Spain, we’d read short stories about men from Barcelona and Madrid trying to take one another’s place; the professor told us it was the product of anxieties about masculinity and class-jumping due to a national history and economy I was new to learning about. It all read as vaguely homoerotic to me, something I was too embarrassed to offer up in the classroom discussion at the time.

At night in my homestay, I’d go to bed dreaming of someone trying to disappear me, of secret passageways in apartments behind bookcases and mirrors that led someone from one big city to the next, littered with images and storylines I’d only half understood. I found the idea titillating, a rivalry and intimacy only complete after self-annihilation—or sex. So, in a film where two characters look the same and are played by the same person, it’s always in the back of my mind as a viewer: At what point will one try to be the other?

*

I’ll admit I was disappointed by Us when I first saw it in theaters in 2019. Jordan Peele’s Get Out is about as cleanly executed as any genre film can be—everything in the right place, the reveals exciting, yet inevitable as day. By the end, however, Us is less clear-cut and more opaque, and it’s executed with a heavy emphasis on its reveal in the film’s final moments. But the ending brings more questions than answers. What I didn’t like about the disproportionate focus on the reveal—that the two young Adelaides switched places in the hall of mirrors—is that, if you’re only watching for plot, it’s too inevitable, too easy. As a queer viewer, I was much more interested in the other themes and ideas of the film’s unnervingly familiar undergrounds, its subconscious imaginations running through those tunnels.

This version of myself did not, and would not, exist back home.

I now understand the film to be more lyrical and complicated than the focus on the twist would otherwise suggest. The self is a slippery thing. The “us” can be the many selves inside one’s own being. I spent hours wracking my brain thinking of where either Adelaide’s knowledge might end and begin, thinking of how one might possibly erase something they once did from their memory. What if she doesn’t remember she took the original Adelaide’s place? What if she can no longer tell which one she is?

I once had a dream that I was best friends with myself. We were identical and got along famously and had sleepovers in my apartment. During one of these sleepovers, I woke to myself lying on top of me, staring into my eyes. It wasn’t friendly or romantic, it was sinister. Suddenly, my viewpoint changed: I was the one on top of me, looking down at my other self. Then, I woke up.

What if I’m not the one I thought I was?

I couldn’t shake the feeling.

*

Neither “doppelgängers” nor “clones” is ever uttered in Us, because it’s not that these are different people that just look like the others, or that they’re independent beings concocted in a lab. They’re closer than that.

So, what are they, exactly? The Wilson family can’t seem to agree. “It’s us,” Adelaide’s son Jason says, when the four Wilsons finally see their doubles all lined up together, Red and the doubles of Adelaide’s husband and kids having broken into their summer home. At first they think they are simply intruders, a different family standing menacingly in their driveway; but, of course, they look just like them. It’s something they can’t wrap their eyes or minds around. The scene quickly erupts into chaos. It’s clear that the doubles are out for blood, and only one family, only one version of them, can survive.

I couldn’t escape this sense of the other me, tentative and fearful, lurking nearby, ready to remerge what had been divided.

And so, one by one, the Wilsons are forced to kill their doubles. Red, the only surviving double, takes Jason underground, beneath the house of mirrors that leads to the tunnel world from which the doubles emerged, forcing Adelaide to follow. In the film’s big moment of exposition, Red gives us more insight, if still somewhat impenetrable, into how they’re connected: “We’re human too, you know. Eyes, teeth, hands, blood. Exactly like you . . . I believe [humans] figured out how to make a copy of the body but not the soul. The soul remains one, shared by two.”

Red goes on to explain that the actions of those above control the Tethered below, the opposite of what was originally intended when they were formed. It’s a lot of information at once. I sensed my own resistance in this moment because I thought, none of this really matters, it’s all window dressing to explain why these two selves exist. It all seems to inhibit the more interesting ideas that put people in the theater seats: What if there’s another one of you, standing in your driveway? What are they like? What do they want? What would you trade from your own life and give to them to preserve the rest?

*

The year before graduate school, I lived in an apartment across the street from a strip of gay bars in San Antonio, the music and bass drifting up from its interiors calling me toward it each weekend night. It was hot in Texas and the summer heat gave me an excuse to show off the legs and youth I knew were fleeting. I’d dance the night away hoping to meet someone. I wasn’t as precious about my purity as I’d been in Spain, more consciously embracing this new look toward pleasure. Yet, I couldn’t escape this sense of the other me, tentative and fearful, lurking nearby, ready to remerge what had been divided.

A queer person is used to keeping secrets, telling lies, sectioning off parts of themselves. I spent many years wishing that parts of me weren’t real, and, eventually, they became that way. I had forged two selves. I could assign all the bad stuff to the “pretend” me. All the things I didn’t like about myself, that I was ashamed of, that I didn’t want anyone—myself included—to know, were kept away and pushed onto the flimsy sketch of myself that lived somewhere in my head, but whom I never had to acknowledge.

That other self, his first sexual experience was not one he signed up for. So sex became something I was always running from, hiding away, burying down deep in a mental basement, just like the one that it happened in. It was too much to think about, something that wouldn’t be pulled out from me until therapy over a decade later, so, accordingly, I just pretended none of it was me. I was not that person. None of it counted. It became easier than I thought it would be to simply not think about my actions I didn’t want to associate with myself, to not think of the more complicated version of myself I’d pushed down below. The version of myself that, try as I might, I remain tethered to.

*

When I revisit Us, I see myself in the reflection of the television screen, watching young Adelaide, who will become Red, watch herself watching something that will drive her to her end. I watch her in those early scenes, drawn to mirrors and different reflections and refractions of herself. Sometimes fearful of them, sometimes succumbing to the horrors the world will soon throw at her. My own reflection makes me, ever so briefly, consider the person in the screen, the person I’ve become since the last time I watched. How I’ve gone on each year to find myself a little more, and resolved to take myself with me.

_________________________________

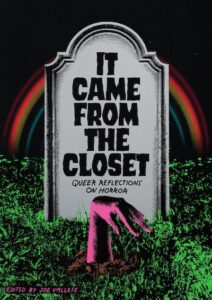

From It Came from the Closet: Queer Reflections on Horror edited by Joe Vallese. Copyright © 2022 by the author and reprinted with permission of Feminist Press.

Steffan Triplett

Steffan Triplett is a Black, queer essayist from Joplin, Missouri. His first book, Bad Forecast, is forthcoming from Essay Press (2024).