The Mankiewicz Brothers’ Biographer Weighs in on David Fincher’s Mank

Sydney Stern on the Beauty and Limits of Capturing Icons on Screen

On December 4, Netflix subscribers will start streaming Mank, David Fincher’s biopic about Herman Mankiewicz, the Hollywood screenwriter who wrote the original script for Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. Mank is a cinematic feast that requires neither familiarity with Herman Mankiewicz nor prior exposure to Citizen Kane to enjoy it. But as with most works of complexity, the more one brings to it, the richer the experience. As it happens, I bring a great deal. I call it knowledge. The less charitable might call it obsession.

I spent the last decade researching and writing a dual biography of Herman and his younger, more successful brother, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, writer/director of, among others, the classic All About Eve and the notorious Cleopatra. Before he became a screenwriter, Herman was a New York newspaperman, a celebrated wit and Algonquin group habitué, a theatre critic for the New York Times and New Yorker, and a playwright collaborating with George S. Kaufman. Unfortunately, Herman was also an alcoholic and chronic gambler. He originally went to Hollywood in 1925 for a short writing assignment, intending to work there just long enough to pay off a gambling debt. Instead, he stayed for the rest of his life, despising the movie business but never managing to leave it. He drank himself to death in 1953 at the age of 55.

When I heard about David Fincher’s interest in Herman, I had been working on the book for several years. His father, writer and journalist Jack Fincher, had written a script in the 1990s and though Jack died in 2003, David still wanted to make the film. I had mixed feelings about the idea of a biopic. Whenever I was asked what I was working on, “the Mankiewicz brothers” drew responses that ranged from a recitation of favorite Mankiewicz films to blank stares to “Are they any relation to” [choose one or more]: Ben Mankiewicz, the Turner Classic Movies host; Josh Mankiewicz, Dateline reporter; Frank Mankiewicz, political operative and pundit; John, Don, or Tom Mankiewicz, all successful screenwriters. After reeling off branches of the Mankiewicz family tree for years, I was excited by the possibility that Herman might become a household name.

On the other hand, I was also apprehensive. Movies are so much more evocative than books that I knew no matter how accurate my research, how convincing my writing, and even how widely my book might be read, Mank’s Herman was going to be the Herman Mankiewicz for the ages. Although I knew the Finchers had worked on Herman for years before I came on the scene, by then I had become proprietary.

In July 2019, Netflix announced a deal to produce the picture. David Fincher would shoot entirely in black and white, as he had long insisted, and Gary Oldman would play Herman. Just before my book’s October publication, Netflix announced more casting choices, including the characters about whom I most cared. Tom Pelphrey would play Joe, and Tuppence Middleton would be Herman’s wife, Sara. Or as Herman infamously dubbed her, Poor Sara. Tom Pelphrey won my heart when he told an interviewer asking how he prepared that they were lucky because “a very thick, pretty detailed biography” of Herman and Joe had been released only a few weeks before they began shooting. I was already a fan of Tuppence Middleton’s after following her as the platinum blonde Icelandic disc jockey in Netflix’s Sens8, and I decided that the real Sara (whom I secretly thought of as my Sara) would be pleased as well.

Fincher shot from November 2019 to February 2020, wrapping just ahead of the Covid-19 pandemic. Publicity photographs began to appear in September, all handsome and beautifully composed. In October, they released the trailer and to my surprise, the two-and-a-half minute montage brought me to tears. I had already seen a draft of Jack Fincher’s screenplay, so I was prepared for dialogue and events I knew intimately—many were in my book. But watching people who had lived in my head for ten years come alive on the screen was unexpectedly moving. And surreal.

That was just the appetizer. I don’t think anything could have prepared me for the movie itself. Its formal qualities—the costumes, sets, soundtrack and especially, the cinematography—were spectacular. But for me, it was all about the story. I knew these people. I had replayed these events millions of times. Now I was watching them unfold on the screen. Even weirder, they seemed to play out in a kind of strange, reverse-engineered version of Citizen Kane. I was riveted.

Stylistically, Mank is both a twenty-first century tribute to the world of Golden Age Hollywood studios and their films, and an unabashed homage to Citizen Kane. Both are biopics, developing character portraits through a succession of flashbacks. In Citizen Kane, a reporter seeks to understand the late press lord Charles Foster Kane by interviewing his intimates, hoping that Kane’s dying word, “Rosebud,” will provide the key to his character. The interview flashbacks follow Kane from boyhood to idealistic young newspaperman to embittered recluse.

Mank, the story of the creation of Citizen Kane’s first draft, opens in 1940, with Herman, forty-three, bedridden and recuperating from an automobile accident. Orson Welles (Tom Burke), a twenty-four-year old theatrical and radio star, has hired him to write a biopic about newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst. Welles, who has never made a film, has been given an unprecedented contract from RKO Pictures to write, produce, direct, and star in a film of his own choosing. Herman not only knows how to write a screenplay, he knows Hearst. So with only a few months to write the script, Herman has been exiled to a Victorville, California dude ranch in the Mojave Desert where John Houseman (Sam Troughton), a Welles colleague acting as his editor; Fraulein Freda (Monika Grossman), a German nurse and physical therapist; and Rita Alexander (Lily Collins), an English secretary, are charged with keeping him comfortable, productive, and on the wagon.

As Herman dictates “American” (the title of Citizen Kane’s original screenplay), flashbacks follow his spiral of self-destruction amidst the glamour of Hollywood’s 1930s studio system. Here is Herman leading writers George Kaufman, Sid Perelman, Ben Hecht, and kid brother Joe into a Paramount story meeting where they patronize their boss, David O. Selznick, while enjoying his fine cigars. There is Herman arriving at Hearst’s San Simeon estate in a drunken stupor, only to befriend Hearst’s mistress, former Brooklyn showgirl Marion Davies (Amanda Seyfried); impress Hearst (Charles Dance); and gratuitously insult Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer chief Louis B. Mayer and MGM production head Irving Thalberg (Arliss Howard and Ferdinand Kingsley), who are also Hearst’s guests. Here is Herman with Mayer again, but this time he is a valued employee of Mayer’s, introducing Joe to his MGM chief.

Herman is also involved in a political subplot based on an actual fake-news campaign that MGM generated in California’s 1934 gubernatorial election to help defeat socialist candidate Upton Sinclair. Herman’s role in the events is fictional, but the storyline illuminates the powerful studios’ sheer ruthlessness. It also provides Herman with a motive so compelling he is willing to risk what is left of his career to write a scathing screenplay about the powerful Hearst.

At the same time, it offers a less forgiving interpretation of Herman. Despite his obvious flaws, Herman so far has appeared as an understated hero, wise, witty, professionally respected, insightful, generous, and genuinely kind. Yes, he drinks and gambles and says what he shouldn’t. But given the greed and idiocy that surrounds him, his anger and ironic distance seem understandable, even evidence of his superiority. But when Herman bursts into Irving Thalberg’s office to beg him to cancel the anti-Sinclair campaign, Thalberg holds up a mirror: “I know what I am, Mank. When I come to work, I don’t consider it slumming. I don’t use humor to keep myself above the fray. And I go to the mat for what I believe in…. But you, sir. How formidable people like you might be if they actually gave at the office.”

In short, Mank’s hero is also a man whose low opinion of what he does means never having to say he cares. He’s a cop out.

But now, out there in the desert, this wasted man realizes that this script he is dictating, casually and just for the paycheck, is not only good or possibly even great. It may be his one last opportunity to see if he has it in him to create a work of real meaning.

At the end of Citizen Kane, the reporter comes to understand that finding the meaning of the word “Rosebud” would not have solved the mystery of Charles Foster Kane. “Maybe Rosebud was something he couldn’t get or something he lost, but it wouldn’t have explained anything. I don’t think any word explains a man’s life,” he tells another reporter.

We are only thirty-one minutes into Mank’s two hours, twelve minutes when Herman explains what Citizen Kane—and by implication, Mank—can and cannot do. “You cannot capture a man’s entire life in two hours. All you can hope is to leave the impression of one.”

Even the heftiest doorstoppers, the so-called definitive biographies, share that limitation. There is no such thing as explaining a person’s entire life. Or even defining an entire character. But after a decade in Herman Mankiewicz’s company, I already miss him. It’s reassuring to know I’ll have Mank’s two-hour impression of him to revisit and savor, now and then. Even if it’s really Gary Oldman.

__________________________________

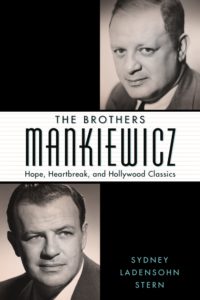

The Brothers Mankiewicz: Hope, Heartbreak, and Hollywood Classics by Sydney Stern is available now via the University Press of Mississippi.

Previous Article

Grace Lynne Haynes on the Coexisting Beauty ofDarkness and Light

Next Article

How Hard Is It to WriteAbout America?