Berta Cáceres is perched on the edge of the sofa, glued to the tiny television. It’s early and her husband Salvador Zúñiga is still asleep. The children, Olivia, Bertita and Laura, all under the age of five, are busy playing as Berta watches extraordinary events unfold in Chiapas, southern Mexico. This was the day the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between Mexico, Canada and the US came into effect.

It was also the day of the Zapatista uprising. Wearing a black ski mask and army fatigues, Rafael Sebastián Guillén Vicente, soon to be known as “Sub-comandante Marcos” and the public face of the indigenous insurrection, declared war on the Mexican government on live television. “We, the Zapatistas, say that neo-liberal globalization is a world war, a war being waged by capitalism for global domination,” Marcos said in a statement of intent, as 3,000 armed guerrillas took control of towns from the mountainous highlands to the tropical rainforests across Chiapas. “That is why we are joining together to build a resistance struggle against neo-liberalism and for humanity,” he exclaimed. A leader was born.

*

“Salvador, wake up! You have to see this, indigenous people are revolting in Mexico,” Berta urged her husband, trembling with excitement. “This is it. This is what we’ve been missing. We need to mobilize los pueblos indígenas, go on the offensive and demand our rights!” The events in Mexico were a light-bulb moment for the twenty-four-year-old. Another leader was born.

The newly-weds’ small house on the outskirts of La Esperanza was soon filled with members of COPINH, the organization they had founded in March 1993. They released a public statement in solidarity with the Zapatistas and Marcos’s demand for work, land, housing, food, health, education, independence, liberty, democracy, justice and peace.

COPINH was founded to revive Lenca fortunes in Honduras. It was, the couple believed, the right political moment to be talking about human rights, indigenous rights and demilitarization in the same breath. In 1992 (the year peace accords ending the civil war were signed in El Salvador) Rigoberta Menchú, a Guatemalan K’iche’ Maya feminist leader, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, while the UN declared 1993 the first International Year of the World’s Indigenous Peoples.

The Zapatista uprising gave COPINH confidence, but, unlike the Zapatistas, COPINH was not about to engage in armed struggle. Berta and Salvador had returned from El Salvador weary of bloodshed. In the midst of its civil war, they had debated class, gender, socialism, and even the limits of armed struggle with guerrilla commanders such as Fermán Cienfuegos. The couple saw dirt-poor campesinos driven towards the guerrilla movement by hunger, not ideology, and were baffled by claims that El Salvador had no more natives while fighting alongside men and women who lamented their sacred lands. Berta and Salvador came home tired of war but excited by the democratic possibilities in Central America after decades of military rule, death squads and social repression.

The events in Mexico were a light-bulb moment for the twenty-four-year-old. Another leader was born.

Still, the Zapatista discourse helped the fledgling group grasp how indigenous rights went hand in hand with the protection of land, forests and rivers. Safeguarding indigenous communities meant defending their territories. Soon after COPINH unveiled a strategy of direct action by organizing roadblocks, sit-ins and continuous protests to stop illegal logging in the Lenca community of Yamaranguila, a few miles west of La Esperanza. They were loud, stubborn and successful, making instant enemies of local landowners but eventually forcing out over thirty logging projects from ancestral forests across three departments. Berta and Salvador understood that indigenous rights were human rights. However, for the state and most other Hondurans in 1994, indigenous people didn’t exist. The pre-Hispanic communities were considered living fossils, the stuff of history and folklore, not an ancestral community with rights. In response, COPINH hit upon a simple idea that turned out to be a stroke of genius.

*

In June 1994, thousands of Lencas descended from the mountains in western Honduras and marched on the capital Tegucigalpa, to present the Liberal government of Carlos Roberto Reina Idiáquez with a list of demands including schools, clinics, better roads and, most importantly, recuperation and protection of ancestral territory. Scores of men, women and children from other indigenous communities—Maya, Chorti, Misquitu, Tolupan, Tawahka and Pech—joined the peregrination along the way. From the north coast came the colorfully dressed, drumming Garifunas: Afro-Hondurans who descend from West and Central African, Caribbean, European and Arawak people exiled to Central America by the British after a slave revolt in the late eighteenth century.

Honduras had never seen anything like it. Curious crowds from the mixed Spanish and indigenous mestizo majority came to help the marchers with food, clothes and bedding during the six days it took to walk over 200 km. The pilgrims were even warmly greeted in the capital, where indio was a common racist term for those with suspected indigenous roots who mainly worked in low-paid jobs. Nobody expected this. Berta and the Lencas marched under a giant banner celebrating a great chieftain: “Lempira viene con nosotros de los confines de la historia” (Lempira comes with us from the confines of history).

When the Spanish invaded in 1524, the Lencas were the largest ethnic group in number and territory, and it was Lempira who united 200 tribes in battle against the invaders. After Lempira was killed in 1537, the Lenca believed a mystical woman would rescue them and restore the defeated nation, or so the myth went. In front of huge crowds and TV cameras, Berta and Salvador impressed with their rousing speeches. So did Pascuala Vásquez, a petite Lenca elder known to everyone as Pascualita. “We’re not here because we love the capital city where there are bridges but no rivers, we’re here because we have many needs in the communities, and we have rights, and we demand that the government sits down with us and listens,” she said. The energy and purpose conveyed by this wizened woman with her clarion voice earned her the nickname primera dama, first lady. It was the start of something, like a coming-out parade, which promoted the indigenous people of Honduras from fossils to citizens.

Diverse indigenous communities joined forces to create a national movement demanding recognition and rights through hunger strikes, roadblocks and several more pilgrimages—in turn emboldening even bigger multitudes from isolated mountain and coastal villages to march on the capital. In this jubilant atmosphere, Berta connected the dots from local to global.

One Garifuna leader, Miriam Miranda, recalls Berta pausing the march to paint anti-imperial murals on the walls of the US airbase, Palmerola. Militarization and repression, Berta explained as she wielded her paintbrush, go hand in hand with the neo-liberalism pushed by President Reina’s predecessor, Rafael Leonardo Callejas, because it is an economic and political model which must destroy some of us in order to thrive. For the first few years, victories came thick and fast. The most important was the ratification of the 1989 Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention of the International Labour Organization, known as ILO 169, a binding accord guaranteeing the right to self-determination. Honduras signed up in 1995, in part thanks to pressure by Liberal congresswoman Doña Austra who promoted indigenous and women’s rights demanded by COPINH, OFRANEH and others, which Reina’s more progressive government was open to. It was the first time Honduras was legally recognized to be a multicultural, multi-ethnic, multi-lingual society.

San Francisco de Opalaca, the birthplace of Pascualita, was declared an indigenous municipality—a landmark post-colonial triumph. A specialist prosecutor for indigenous issues was created to tackle crimes such as violating the right of indigenous communities under ILO 169 to free, prior and informed consultations for projects which could impact on their land, culture or way of life. ILO 169 played a crucial role in the recuperation of small but significant territories lost after colonization: over the next few years, COPINH helped more than 200 Lenca communities acquire land titles across five departments. The treaty was the precursor to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples which Honduras adopted in 2007. Both international tools deal with the mandatory rights of indigenous peoples to their cultural and spiritual identity, habitat, food, water, self-government, control over territories and natural assets, respect and inclusion. Of course, these instruments didn’t put an end to the violation of ancestral and community land rights. But they set the legal battleground for Agua Zarca and hundreds of other projects sanctioned for indigenous territories with blatant disregard for ILO 169.

*

The new indigenous movement injected energy and optimism into the country’s flagging social movement, sociologist Eugenio Sosa told me over coffee in Tegucigalpa. In the mid-1990s, banana workers’ and campesino unions were in crisis, having grown rather too cosy with the government and the United States after the 1954 strike. Meanwhile, new exploitative industries such as the maquilas or assembly factories strongly discouraged unionization; student and socialist groups had been decimated in the dirty war, leaving only the teachers and fledgling human rights groups battling to find the disappeared, demilitarize the country and promote women’s rights. The indigenous movement with its dynamic leadership worried the ruling elites—and Uncle Sam. Despite no sniff of armed insurgency, rumors spread that Honduras could become the next Chiapas, and the response was predictable. More counterinsurgency—but this time with a softer face, the so-called battle for hearts and minds.

World Vision, the American evangelical aid charity with an anti-communist vocation, appeared in neglected Lenca communities alongside USAID, offering maize, medicines and housing. US soldiers helped construct schools and hospitals. “It was a clear reaction to the uprising by indigenous people in a strategically important zone for the US,” said Salvador Zúñiga. “There was constant scaremongering about armed insurgency, but the real fear was that people were starting to understand and demand their rights, and COPINH was achieving victories through unarmed mobilizations.”

*

Berta was raised in a staunch Catholic churchgoing family, her husband Salvador as an Evangelical Christian. Back in the 1960s and 70s most people were either ignorant or ashamed of any indigenous heritage, after centuries of ‘civilization’ policies imposed by the state and Church which had robbed native peoples of their language, customs, religion and collective pride. Yet, both Cáceres and Zúñiga proudly identified as Lencas, even though their parents didn’t.

Berta conducted spiritual Lenca ceremonies with her children, and encouraged them to be critical of organized religion, though she never completely rejected Christianity—meeting Pope Francis at the Vatican in October 2014. She admired a progressive Jesus much as she did the murdered Salvadoran prelate, Monseñor Óscar Romero, but was also inspired by the spirituality of First Nation and Native American tribes, and Garifuna and Mayan customs.

COPINH’s pioneering struggle centered on rescuing Lenca identity, customs and traditions. Pascualita, the little old woman who spoke at the march on Tegucigalpa, was a key figure in this aspiration and would become COPINH’s spiritual leader. An oral historian and Lenca legend in her own right, she is instantly recognizable by the bright red clothes that she wears to ward off evil spirits, along with an oversized woolly hat to ward off the chilly La Esperanza wind.

Born in 1952, Pascualita was brought up a Catholic Lenca—part of a churchgoing family with strong indigenous traditions. At their core is a spiritual connection with Mother Earth nurtured through the compostura—smoke ceremonies with offerings such as cacao, candles, firecrackers and the ancient maize-based liquor chicha, banned by colonial powers because they couldn’t tax it. “I taught Berta and the communities we visited the compostura, the river and angel blessings I learned from my grandparents, but nothing was written down,” said Pascualita. “From the beginning, it was a political and a spiritual fight.”

In the early 1990s these ceremonies were still practiced in many communities, but often in secrecy. Berta encouraged communities to revive ancient customs openly and with pride. Today, every COPINH event starts with a smoke ceremony. If you visit La Esperanza, Pascualita is always on call to explain Lenca traditions and COPINH’s role in their rescue.

For Berta, ancestral spirituality and how these spirits bridge the past and the present were fundamental. She helped recover the memory of Lempira as a courageous hero, a symbol of resistance, not just another vanquished native leader. Some would argue that Berta’s greatest legacy is the rehabilitation of Lenca culture. It was no coincidence that outside the courthouse, after the first arrests for Berta’s murder, people were chanting: “¿Quienes somos? ¡Venimos de Lempira!’ (Who are we? We come from Lempira!) Pascualita was there.

Berta and Salvador often visited remote Lenca communities at weekends with the children or cachorros, cubs, as she called them. Just like her own experience of helping Austra, her mother, deliver babies when she was a girl, these excursions on foot and horseback exposed the four children to terrible discomfort and beautiful natural wealth. And they loved it.

“They took the four of us everywhere like suitcases, no matter how bad the conditions. We’d tuck our pyjamas into our socks so we didn’t get bitten by bed bugs and mosquitoes,” recalls Olivia, the eldest. “We were brought up to feel proud of our Lenca culture, and strong enough not to care when the other children and teachers called us indios.”

Berta hadn’t intended to have children so close together, in fact she used to tell her girlfriends at school that she would never get married at all – but then she met Salvador. Four children within six years wasn’t easy. In a classic good cop, bad cop scenario, Berta was the disciplinarian, whereas Salvador was more playful. He was a homebody, and became the national figurehead of COPINH, while Berta constantly travelled, forging alliances across the world. Money was tight, and at times they relied upon food packages from Doña Austra. Behind her back, some relatives called Berta a bad mother who cared more about the indios than her own children. This hurt.

Berta wasn’t like most other mothers in La Esperanza. She hated domestic chores; she wouldn’t let the children watch Cartoon Network or spend hours on PlayStation, like some of their cousins. Instead she brought them microscopes, telescopes and dark-skinned dolls from her travels. At night she would sit the four squabbling children in a circle, to talk through their gripes, or to dance or learn about plants and nature. “All my fun memories are with my dad, but these nightly sessions were very intimate, she would try to open our minds by teaching us right and wrong through spirituality,” said Bertita. “It was hard for her when we were little, but she definitely enjoyed us and motherhood much more as we got older.”

“At home we were little devils,” said Olivia, laughing as she recalled leading a sibling protest armed with homemade placards opposing some parental diktat. Physically, Olivia is the most like her mum. She too is stubborn, charming, rebellious and a persuasive public speaker. Their relationship, however, wasn’t a smooth one, perhaps because they were too similar, perhaps rooted in unresolved grievances. Their relationship was a work in progress when Berta was murdered.

__________________________________

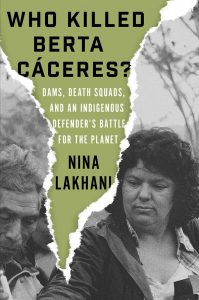

Adapted from Who Killed Berta Caceres? Dams, Death Squads, and an Indigenous Defender’s Battle for the Planet by Nina Lakhani, courtesy of Verso Books.

Nina Lakhani

Nina Lakhani reports on Central America for the Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Global Post, the Daily Beast, and elsewhere. She previously worked for the Independent. She is based in Mexico City.