The Making of a Muse: When Edie Sedgwick Met Andy Warhol

Alice Sedgwick Wohl on Her Sister’s Transformation From Model To Icon

Edie had absolutely no idea where she was going.

She hadn’t even known who Andy Warhol was, and when Chuck Wein tried to tell her, she said, “What’s that? Pop tart?” She told the TV host Merv Griffin when she was on his show, “I came to Andy’s studio with a friend, and I didn’t know Andy and I didn’t really know too much about New York, and he was in the process of making an underground movie, which when I walked in, I couldn’t really tell what was happening. There were lots of lights and people running around doing things, and then there were some people huddled together, with more lights on them, and they were sort of making… sounds.

And all of a sudden I understood they were reading a script, and that was part of the movie, and it was in progress. Well, I just happened to be pushed into a chair in the middle of it, to sit there, and I didn’t really have anything to do with it, ’cause I never would do it otherwise. And I just sat there and from that time on I got up the courage to do some more.”

The film was called Vinyl, and the idea for it had originally come from Gerard, who got tired of being an extra in Andy’s films and wanted to be the star. For his vehicle he chose A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess (and this was years before Kubrick), and Andy claimed he bought the rights for three thousand dollars, which would have been an unthinkable sum for him, who was so careful with money, but then neither Gerard nor Ronnie Tavel, who was Andy’s regular scriptwriter at the time, managed to write a screenplay. Instead, Tavel wrote some scenarios and finally came up with a script on the theme of sadomasochism.

But how was Edie to know that what they saw in her was not talent but simply the way she was, transcribed onto the screen?The cast consisted of five guys—Gerard and another pillar of the Factory who went by the name Ondine, plus an actor, a florist acting the part of the sadistic doctor, and the victim, a boy called Larry Latreille—and filming was underway when in came Edie with her silver-streaked beehive hair, wearing a black tank-top dress and a leopard-skin belt. On an impulse (and to the annoyance of the others), Andy told her to go sit on a trunk right next to the action, just sit there.

And that’s all she does for most of the film, she just sits there, smoking and occasionally drinking out of a white cup. You can see she doesn’t quite know what to do with herself, but then the music takes over and Gerard starts dancing, jumping up and down and thrashing around, and she can’t help herself. She begins to sway and move her head, closing her eyes and moving those long white arms about languorously, dancing without ever stirring from her seat. Most of the time she sits there detached, crossing and recrossing her legs, looking on and looking away, smoking and flicking ashes off her cigarette, and all the while some serious S & M stuff is going on right next to her.

And afterward, when they saw what they had, there was Edie, completely dominating the screen. You can’t take your eyes off her. Ondine said that when they saw the reruns they got an inkling of what was happening with Edie in the Factory; he said she had a power they hadn’t even suspected. As Ronnie Tavel put it, “She ended up stealing the film and becoming a star overnight.” But how was Edie to know that what they saw in her was not talent but simply the way she was, transcribed onto the screen?

And is she to be believed when she tells Merv Griffin that was the first time she went to the Factory? Because Ronnie Tavel says Andy merely posed with the movie camera that day so David McCabe could take a picture, and then he walked out, leaving the cameraman Buddy Wirtschafter to take over. According to Tavel, Andy was mad at Gerard, so he was laying into him and deliberately sabotaging the film. And as Tavel complained to Patrick Smith, Andy also sabotaged Tavel himself and his intentions for the film, because the script called for men only, and when Edie showed up, Andy stuck her into the middle of everything.

The technical evidence bears Tavel out: at the time it was Andy’s practice to keep the camera stationary while shooting; that way he could walk off and let it watch the action for him. In effect, he treated the camera as a surrogate for his eye. However, when Wirtschafter took over, he had to make a sudden adjustment, and that caused it to move. Andy would never have moved it, nor would he have walked out if that had been the very first time Edie Sedgwick showed up at the Factory.

However, what I find striking in all this is not just that Edie handled Merv Griffin so artfully, it’s something Ronnie Tavel says. He says Andy was going around a lot with “date debutante…social register…beautiful Edie Sedgwick,” and she was bringing him a lot of publicity and attention from the gossip columnists. Wait a minute: They had met on March 26, Vinyl was filmed within days of their meeting, and they were already in the gossip columns?

The main thing now, however, was that Edie turned out to be mesmerizing on film, and right away Andy wanted to make a movie that was just about her. It’s called Poor Little Rich Girl; it was made in the last days of March and the very beginning of April, and it records two reels’ worth of her day. I knew the movie was famous, but when I finally saw it I was bewildered, because at first all there was to see was mounds of white foam like bubble bath, heaving and stirring about against a dead-black background.

True, there are dark smudges indicating Edie’s hair and eyes, so you can keep track of her, although it hardly matters in the beginning because for the first three minutes the camera focuses on her head and face while she sleeps and nothing moves. Then a male voice announces the title and she sits up and gets right on the phone. You hear her talking, asking the time (four o’clock), and chatting a bit. Then she calls and orders five orange juices and, um, two cups of coffee sent up (that’s one skill she had, she knew how to order stuff by phone, how to get service so she didn’t have to do things for herself).

She pulls out a cigarette, lights it, smokes, sits there looking about, and then she must turn something on because suddenly you hear the Everly Brothers singing “Bye Bye Love” and one song after another after that, and sometimes you hear her singing along. What you see is all very blurry, although when she stands up you can tell she’s wearing a poufy white dress and when she takes it off it’s clear that all she has on is a minuscule black bra and panties. Now she lies on her bed for a minute, bicycles her legs and does some stretches, then she gets up and goes over to her dressing table, finds a cigarette and smokes that, sits down, tries dialing the phone, pours a bunch of pills into her mouth and washes them down with what’s left in her cup, and from time to time her head and arms move to the beat.

This goes on for a good half hour until eventually the reel runs out—you see that right on the screen—and the numbers of the new one appear and count down. And now suddenly, there’s Edie’s bare white midriff, navel and all, perfectly distinct, framed top and bottom by her black lace underwear. The camera zooms out to show her sitting on the edge of her bed, and you see she’s wearing sheer black tights. Now you really watch, because the camera focuses on her face, and it catches every flicker of expression.

I can’t get over how enchanting she is. She calls out, “Chuck? Chuck, you going to wake up?” and he wakes up, and for the whole rest of the film the two of them chat, although he remains off-screen. (That’s Chuck Wein, who had introduced himself into the filmmaking process and wanted credit as co-director.) Edie fills her pipe from an envelope and asks Chuck if he wants some, but he says, “Not yet.” They tell each other their dreams until somebody calls and she talks for a long time and makes faces whenever she has to listen, and now he puts on music that’s so loud you can’t imagine how she can hear and you can’t understand a word she says.

Finally, she hangs up and they start chatting again, but the conversation is vague and Edie keeps losing the thread. Anyway, it’s hard to make out the words until suddenly she asks, “What am I going to do?” and he says, “Call the bank?… Marry somebody rich.” She responds that she knows a lot of rich people and they’re all pigs; you can’t bear to be around them. Then she gives him a charming look and says quite distinctly, “I’d like to kill Grandma, just do away with her.” What? I’ve listened to the tape over and over, and I’m quite sure that’s what she says, because she giggles and Chuck says something about killing Grandma.

It also tells you something about Edie: she could never be anything but herself, and as herself she was absolutely riveting on-screen.Edie just laughs and fills her pipe. At one point she tells him, “Mummy says they’re not going to give me another penny, not even for medicine.” (But they did, they always did, or rather Mummy did. God only knows what it cost her.) They talk some more, and after a while he says to her quite matter-of-factly, “I think you should get sick in front of everybody,” and I thought I heard her say that way she doesn’t get fat. (Doesn’t she realize he’s causing her to put her whole self on display? Doesn’t she mind?)

Now she stands up and goes to the closet, pulls out the famous leopard-skin coat, and puts it on over her underwear to show him. “It’s the most beautiful coat in the world,” she says, and explains that it was a gift from a funny Englishman, the one who wanted to give her a lot of money. She takes the coat off, wriggles out of her leopard-skin belt without mussing her beehive hair, and picks up a sleeveless white jumpsuit that she steps into and ties the sash around her hips, so you realize she’s getting ready to go out. She fishes out a very long chain with a locket, puts it on, and starts rummaging in something out of sight where she says with a sly look that she put a hundred-dollar bill, then she gives up and dabs perfume all round her neck.

Chuck tells her to try calling Dominic, he’s going into the other room, and suddenly you hear his voice announcing the title and credits, and that’s the end. It turned out that the lens of the camera had not functioned correctly the first time, so Andy shot another version that doesn’t have the defect and combined the two, putting the blurry part first, because that was what he was like. He set it all up and then he dealt with what came. Andy said if Edie had needed a script, she wouldn’t have been right for the part, which tells you something else about his approach to filmmaking.

It also tells you something about Edie: she could never be anything but herself, and as herself she was absolutely riveting on-screen. When Jonas Mekas saw the film, he was impressed: he wrote that “Poor Little Rich Girl, in which Andy Warhol records seventy minutes of Edie Sedgwick’s life, surpasses everything that the cinema verité has done till now.” But Edie didn’t see it that way: when it was screened at the Cinematheque on April 26, she walked out, convinced that she had been made to look ridiculous.

Andy was transfixed by her. Many years later he wrote, “One person in the 60s fascinated me more than anybody I had ever known. And the fascination I experienced was probably very close to a certain kind of love.” For Andy this is an extraordinary admission, given his evasiveness, his reflexive nonchalance when it came to anything even remotely personal. He adds that she had more problems than anyone he’d ever met, and it occurs to me that he might be defending himself, because by then she was dead of an overdose and a lot of people blamed him for what happened to her.

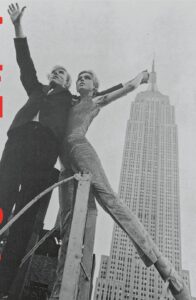

However, there is no question that at the beginning and throughout their first months together, Edie was a wonder in his eyes and, whatever that might mean in his case, he certainly appeared to be in love. There’s no other word for it. Just look at that photograph by Steve Schapiro: there’s Edie in profile looking eagerly straight ahead, and Andy is gazing at her with his head on one side, completely moonstruck. I think the photograph says a lot about their relationship: he’s gazing at her and she’s looking to see what’s ahead for her.

“Love” is not a word I would associate with Edie; what she wanted more than anything was the intense experience of life. She wanted what she called “action,” and while nobody would necessarily have described Andy as “exciting,” given his vague elusive manner and recessive presence, he generated a huge amount of energy around him, and the Factory was a very exciting place to be. More important, Edie was instantly and deeply engaged by the camera, and she must have sensed Andy capturing her. The fact that he thought she was so good on film gave her validation and a focus, neither of which she had ever experienced before; clearly, she felt herself to be affirmed.

___________________________________

Excerpted from As It Turns Out: Thinking About Edie and Andy by Alice Sedgwick Wohl. Copyright © 2022. Available from Farrar, Straus and Giroux, a division of Macmillan, Inc.