In a previous essay I looked at the use of grammar in the recent work of Garth Greenwell, arguing that Greenwell’s employment of specific grammars are utilized for the purposes of meaning-making. In this essay I will be turning toward a different contemporary author whose style similarly benefits from close attention, but who employs that style in ways that differ significantly from Greenwell.

Lauren Groff’s most recent book, Florida, is a collection of stories the original publication dates of which straddle that of her most well-known novel, 2015’s Fates and Furies. As a result of this, we are able to see, in a single volume, something of the shifts Groff is capable of in her work, tonal subtleties which display a mastery of sentence-level craft and which place her work, to my mind, alongside that of similar masters of subtlety, loneliness, and grace, among them Mavis Gallant, Shirley Hazzard, and Jean Stafford. Take, for example, what Groff does with the openings of two separate stories collected in this volume. First from her Best American Short Stories-included “For the God of Love, for the Love of God”:

Stone house down a gully of grapevines. Under the roof, a great pale room.

And now the opening sentence of the volume’s final story, “Yport”:

The mother decides to take her two young sons to France for August.

These two openings well represent the breathtaking swing of Groff’s style during this period: the strange rootlessness of the first example and the steady statement of situation in the second. As with all the stories collected in Florida, both of these are stunning in their ability to create motion out of somewhat sparse parts where what is at stake for the characters is often slippery to define.

“For the God of Love, for the Love of God” is a prime example of this, a story in which, as a bad critic might say, “nothing really happens” and yet which carries its readers so subtly that one is left dazzled and confused, the story’s rural French landscape rendered in brushstrokes that feel both partial and impossibly complete. Even in the opening passage quote above—those two sentences!—we are afforded a sense of being unseated, not by the characters, for we do not even know the characters yet, but by the landscape itself. Here it is again:

Stone house down a gully of grapevines. Under the roof, a great pale room.

Grammarians might note the lack of verbs in both sentences or the fact that, verbless, these are not technically sentences at all but fragments (the boldness of beginning a story with such a move!). And yet these two fragments contain within them a sense of action and movement even if one cannot point to a specific verb.

In order to understand how Groff accomplishes this, we must first remind ourselves of the definition of the grammatical unit known as a preposition. A preposition is a word that generally shows direction, location, or time (there are other uses but I’m simplifying things here), for example: at, about, under, over, past, since, toward, and so on. Prepositions are followed by a group of words that form its object, hence a “prepositional phrase,” for example: at 12 o’clock, about the town, under the table, over the hill, and so on. The purpose of a prepositional phrase is to modify a noun that appears somewhere else in the sentence. You might think of the phrase, then, as a kind of adjective that points to a noun, offering some additional information about it that the reader did not otherwise know.

Like all of Groff’s writing, Florida is a remarkable achievement and one which rewards rereading.It might also be noted here that employing a prepositional phrase sets up a direct expectation for the reader, since the introduction of a preposition asks for the phrase that follows. I will meet you at… or My keys are under… or I’ve been waiting here since… In these examples, we are left wondering what time we’ll meet, what my keys are under, or how long I’ve been waiting, which is simply a way to underscore the grammatical relationship between the introduction of a preposition and the noun that will complete the structure of its required phrase. Remember as well, the complete prepositional phrase is always related to a noun, noun phrase, or pronoun in the same sentence. By way of an exceedingly simple example, in My keys are under the table, the prepositional phrase offers the reader information about the specific location of my keys.

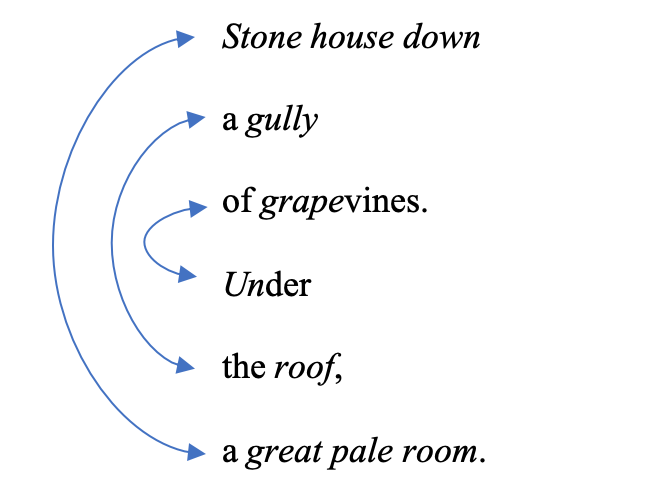

Now let’s return to the opening two sentences of Groff’s “For the God of Love, for the Love of God,” and this time I’ve emphasized the prepositions in bold and the phrases in italics:

Stone house down a gully of grapevines. Under the roof, a great pale room.

I made the claim earlier that these two fragments contain, despite their lack of verbs, a sense of action and motion. This is built into the very design of Groff’s careful implementation of prepositional grammar, particularly in the sense of reader expectation. The first sentence, after its clear statement of subject (Stone house) contains two such prepositional phrases, which, combined, mimic of kind of downward tumbling: down a gully and of grapevines. Once the reader reaches the first preposition (down) she is automatically shifted into a particular expectation that requires the completion of a noun (a gully), after which we are dropped onto a second preposition (of) which does much the same thing (grapevines).

Groff makes a similar move in the second sentence, but this time she reverses the order of the prepositional phrase and the noun to which it points, placing the prepositional phrase at the start of the sentence to serve dual purpose as an introductory phrase (which is why it’s set off by a comma). One might return to the notion of tumbling downhill as introduced in the preceding sentence, for what Groff does after this initial preposition is to reach a kind of flat space, an angle of repose, at which point the reader can stop moving as we enter a great pale room.

Part of the effect of this can be located in the rhythm of these two sentences and how that rhythm further bears out its effect and meaning. Robert Hass reminds us that poetic scansion is idiosyncratically different for each reader, but this is how I read Groff’s rhythm (stresses italicized):

Stone house down | a gully of grapevines. | Under | the roof, | a great pale room.

I’ve broken the above into what I read as the sentence’s poetic feet—those units of poetic scansion, generally of two syllables, that form the basis of our close readings of verse. Note that I am also perhaps fudging the feet here in parsing out the first three stressed syllables as one foot (if you want the technical terms, this would be called a molossus but one could also read it as three monosyllables or as a spondee and one monosyllable; I’ll leave you to look that stuff up on your own).

Despite the fact that these are, at a glance, sentences of different syllabic content (the first sentence contains nine syllables; the second eight), Groff’s metric pattern here reinforces the ways in which these two sentences are mirror images of each other. In the first, she begins with—as I read it—three stressed syllables in a row, an exact reflection of the ending of the second sentence. In fact, this mirroring connects these two sentences rhythmically in an almost identical inversion best shown here:

In the center (of grapevines. | Under), Groff mirrors the rhythms of stress/unstressed syllables (a poetic trochee). Above and below that (a gully | the roof,), she gives the reader a classic iamb, unstressed/stressed. And, as we’ve already shown above, she begins and ends with those three stressed beats: stone house down | great pale room (the rhythm of which is boom boom boom).

As I pointed out earlier in this essay, what this accomplishes for the reader is a sense of motion in a scene which is, technically, devoid of motion (hence no verbs). The stone house is just there, doing what houses do: nothing. In the house is a room. That’s it. And yet under Groff’s direction the reader tumbles down the gully and lands in this great pale room, swinging through a deliciously unsettling description of a landscape that leaves us feeling moved but also strangely confused. Where are we? Where have we been? What’s in this great pale room anyway?

The power of “For the God of Love, for the Love of God” is held in exactly these questions for it is, as I stated at the outset, a story in which “nothing really happens.” We are occupying a large stone house in the French countryside, a house in which two couples engage in petty rivalries and affairs and in which a young boy, Leo, caught between caregivers, is mostly left to himself. Groff’s style throughout is most declarative, so much so that it remains almost invisible, free of filigree or even intent. And yet this is, of course, hardly the case. Groff’s couples seem lost in their own lives, from the very idea of possibility itself, a fact that is, once more, shown in the grammar of her sentences. Here is the scene in which Mina, Leo’s new caregiver, arrives at the airport:

They were still wet when they arrived at the airport. Genevieve’s dress was soaked at the shoulders and back, her hair frizzed in a great red pouf. Leo looked molded of wax.

Mina, on the other hand, was fresh even off the plane. Stunning. Red lipstick, high heels, miniskirt, on-shoulder shirt. Earbuds in her ears, accompanied by her own soundtrack. Even in Paris, the men melted from her path as she walked. Amanda watched her approach, her throat thick with pride.

One more year of college, and the world would blow up wherever Mina touched it. Smart, strong, gorgeous, everything. Amanda could hardly believe they were related and found herself saying the silent prayer she said whenever she saw her niece. The girl hugged her aunt hard and long then turned to Leo and Genevieve.

Leo was looking up the long stretch of Mina, his mouth open.

One of the grammatical decisions made here is a deemphasizing of action. These are largely characters whose self-purpose has become hazy—both to themselves and to each other—and so Groff goes to to be as the verb of choice: “they were still wet”; “Genevieve’s dress was soaked”; “Mina, on the other hand, was fresh.” Note that Leo might have “looked up the long stretch of Mina,” but instead he “was looking.” Only the last of these is an example of passive voice (the rest are compound verbs that nonetheless sound passive) but my point is that Groff’s choice of verb structures is purposefully hazy and nonspecific. Even the active verbs are mostly weak: watched, looked, found, saw. The only verb here that offers any real action is hugged, a verb used, perhaps, to underscore the raw physicality of this new arrival.

In the center of this scene, Groff moves to stuttering fragments that offer fleeting glimpses of their subject (highlighted here):

Mina, on the other hand, was fresh even off the plane. Stunning. Red lipstick, high heels, miniskirt, on-shoulder shirt. Earbuds in her ears, accompanied by her own soundtrack. Even in Paris, the men melted from her path as she walked. Amanda watched her approach, her throat thick with pride.

Note that the sentence Earbuds in her ears, accompanied by her own soundtrack indeed includes a verb but it is a verb (accompanied) that does not refer back to earbuds or even ears but instead returns us to the start of the paragraph, to Mina herself, the effect of which is to underscore, in this brief moment, how Mina’s physical presence has, in a sense, erased Mina herself, has erased her as a thinking feeling emotional being and has replaced her with a symbol, a kind of self-semiology which is nonetheless informed by the scene’s observers, most importantly her aunt, Amanda. In this moment, the moment of her arrival, Mina is less a person and more an abstract emblem (a signifier) of youth and beauty. We are afforded fragments of a view (lips, heels, skirt, shirt) and an anecdote about men melting from her path. What this all amounts to is information not about Mina herself but about the characters around her and how she is viewed by them.

Under Groff’s direction the reader tumbles down the gully and lands in this great pale room, swinging through a deliciously unsettling description of a landscape that leaves us feeling moved but also strangely confused.And yet Mina is, although a latecomer, the heart and soul of this story, and we come to realize that her own self-understanding is not so different from that of her observers. She knows she has power, and youth, and agency, all of which are evidenced in the story’s final, blisteringly beautiful paragraph:

This sky huge with stars. Glorious, Mina thought, as she walked toward them. The cold in the air, the smell of cherries wafting up from the trees, the veal and endives cooking in the kitchen, the pool with its own moon, the stone house, the vines, the country full of velvet-eyed Frenchmen. Even the flicks of candlelight on those angry faces at the table was romantic. Everything was beautiful. Anything was possible. The whole world had been split open like a peach. And these poor people, these poor fucking people. Were they too old to see it? All they had to do was reach out and pluck it and raise it to their lips, and they would taste it, too.

Mina is, as we learn in the paragraph just before this one, 21 years old and sees herself rising into a world filled with possibilities; in fact, her imagination of her own future is very much in kind with that which her aunt Amanda has similarly envisioned. This moment, this ending, reminds of Eliot’s Prufrock, who, similarly arrested by his age and the mediocrity of his soul, cannot “dare to each a peach,” and of the terror and beauty of Denis Johnson’s “Car Crash While Hitchhiking,” a story which memorably ends thus:

It was raining. Gigantic ferns leaned over us. The forest drifted down a hill. I could hear a creek rushing down among the rocks. And you, you ridiculous people, you expect me to help you.

What Groff does at the end of “For the Love of God, for the God of Love,” is, of course, a move of a much different sort than Johnson’s, but her repetitions and her querulousness here mirror that story’s grammatical diction and effect. Note first how she starts with a fragment not dissimilar to those which began this story. “This sky huge with stars.” Then a full sentence: “Glorious, Mina thought, as she walked toward them.” And then a series of images that, unlike the story’s opening, do not tumble—their rhythm precludes this—but rather gather as as sensory information, not unlike those brief, skating glances that gave us our first visual data about Mina in the airport:

The cold in the air, the smell of cherries wafting up from the trees, the veal and endives cooking in the kitchen, the pool with its own moon, the stone house, the vines, the country full of velvet-eyed Frenchmen.

Note how Groff frontloads many of these little phrases with noun and verb pairings that give it a sense of action. The verb form she’s employing here, the -ing verb, could be built upon to make these fragments into independent clauses by converting them into present participles. In order to do this, she would have needed to add a helping verb as in “The smell of cherries was wafting up from the trees,” a perfectly correct sentence but one which ruins the effect that Groff is so effortlessly employing here. Instead, she runs the phrases together by eliminating the helping verbs and leaving the -ing verb forms intact, the effect of which is to present ongoing sensory information removed from any sense of human agency. The smell wafts of its own accord; the veal and endives cook themselves; the pool contains its own moon; and so on, landing, at last, upon the velvet-eyed Frenchmen who are, in this sentence-that-is-not-a-sentence, not unlike the moon, the smell of cherries, the stone house: part of the landscape and topography itself, the sensory details of Mina’s young, vibrant existence. Her world is alive and she is alive in it.

“Everything was beautiful,” Groff writes. “Anything was possible. The whole world had been split open like a peach.” And then, turning to address the older characters who occupy the stone house with its great pale room: “And these poor people, these poor fucking people. Were they too old to see it?” Groff goes to a stuttering, nongrammatical moment here, the verblessness of “these people, these poor fucking people” void of even the actionless action of the preposition. This too has been scraped away, for indeed, we have learned in the story, that they are, in fact, too old to see it, too old and too wrapped up in the pettiness of their lives. And yet, as Mina tells us, “All they had to do was reach out and pluck it and raise it to their lips, and they would taste it, too.”

The key here is achieving a kind of balance in our sentence writing, a way in which we might stagger the reader’s heart while not drawing attention to the techniques we employ to do so.That Groff gives us this final statement as two independent clauses is telling, for she means each half of this compound sentence to carry equal weight; to do otherwise would be to grammatically betray the story’s theme. Recall that we have been rendered briefly verbless and now are offered a surfeit of verb/pronoun pairings—“reach out / pluck it / raise it”—followed by the comma indicating the start of an additional independent clause, which then shifts the pronoun (it) almost to the end of the sentence. That she drops us on an adverb (too) pulls the story’s theme together, for Mina’s grammar of us and them here is meant, in the end, to be as damning as it is inclusive. They too can pluck that peach but of course, like Prufrock, they would not dare to do so—and Mina knows it, in a sense celebrating her own youth by damning their years.

Like all of Groff’s writing, Florida is a remarkable achievement and one which rewards rereading. The stylistic and meaning-making decisions she has made in “For the God of Love, for the Love of God” are inverted and changed in other stories from the same collection. I offered the opening sentence of the volume’s final story, “Yport,” near the start of this analysis, but let me also be clear that Groff is quite capable of running a long, complex, compound sentence when it suits her. This, from the opening of “Ghosts and Empties”:

I have somehow become a woman who yells, and because I do not want to a be a woman who yells, whose little children walk around with frozen, watchful faces, I have taken to lacing on my running shoes after dinner and going out into the twilit streets for a walk, leaving the undressing and sluicing and reading and singing and tucking in of the boys to my husband, a man who does not yell.

I admit to some temptation to examine the grammar of this beautiful, emotionally fraught sentence, but let me instead ask the reader to think about it on her own: Groff is a master of syntactical balance; look how she holds “a woman who yells” against (or with) “a man who does not yell,” and places all the sentence’s attendant information between, its rhythms (to me) presenting a series of small platforms upon which the reader might pause to observe the stress-fractured domesticity of the scene. (Apparently I have more temptation to examine this grammar than I anticipated.)

The key here, for Groff and for many of us, is achieving a kind of balance in our sentence writing, a way in which we might stagger the reader’s heart while not drawing attention to the techniques we employ to do so. I have sometimes used the verb ensorcell to underscore the process of drawing in the reader’s heart unawares. It is an archaic verb meaning to enchant. That is, I think, our work as writers, but like a magician, one ruins the trick if one sees behind the curtain, which is why grammar is such a useful tool in developing meaning.

Groff’s is a grammar of longing and, often, of loneliness in which she situates her characters (often mothers) in a kind of emotional isolation fettered by competitiveness. (She yells; he does not—so which is the better human?) The markers of this isolation are often stark and clear—her stories are sometimes set on islands or in inaccessible cabins, for example—but it is, I think, in the style of her sentences that we best see her mastery, for here are the gears and wheels of her genius, the ways in which she draws upon the reader’s heart, ensorcelling it to her vision.