The Lost Art of Custom-Illustrating Your Favorite Books

On Grangerizing, the 19th-Century DIY Craze

It’s 1795, and you’re a bookish person with a modest library. The trouble is that very few of your books have illustrations, because illustrations are hand-printed and expensive. Fortunately, there is a guy for that. For a price, you can have your books taken apart, enhanced with extra illustrations, and rebound in your preferred style of leather.

Let’s say you own a three-volume set of Revolutionary War history. Your book-binder (because you are the kind of person who has a binder) can add all kinds of things to it: Engravings, letters, autographs, even photographs. These might include memorabilia from your own collection or family history, or things you bought at auction, or items the bookbinder offered for sale. That three-volume set might expand to six volumes after all those treasures were added, and you’d have a truly unique set of books about the Revolutionary War.

The mass-market version of this was a Grangerized book, named after British clergyman James Granger, who published his Biographical History of England, from Egbert the Great to the Revolution in 1769. It was bound with blank leaves, with the expectation that people would add their own prints, which they might purchase from print stalls in London at the time. Nineteenth-century British bookseller Joseph Lilly expanded his copy of Granger’s book to an astonishing 27 volumes through the pasting-in of additional illustrations. This practice came to be called Grangerizing, and its practitioners Grangerites.

Granger sparked a craze for selling illustrations intended for specific titles. Imagine: a new edition of a Dickens novel comes out, and along with it you could buy a set of illustrations that you could paste in yourself (or have bound in at your book-binder’s shop) that were designed specifically for that edition.

Here, for example, is a Grangerized edition of John Sanderson’s Biography of the Signers from 1824, on exhibit recently at the Huntington Library. It’s a book that perfectly lends itself to the practice: in addition to portraits of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, people might have bound in autographs, letters, and other bits of memorabilia.

John Sanderson, Biography of the Signers. New York, n.d. Illustrated by Thomas Addis Emmet. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

John Sanderson, Biography of the Signers. New York, n.d. Illustrated by Thomas Addis Emmet. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

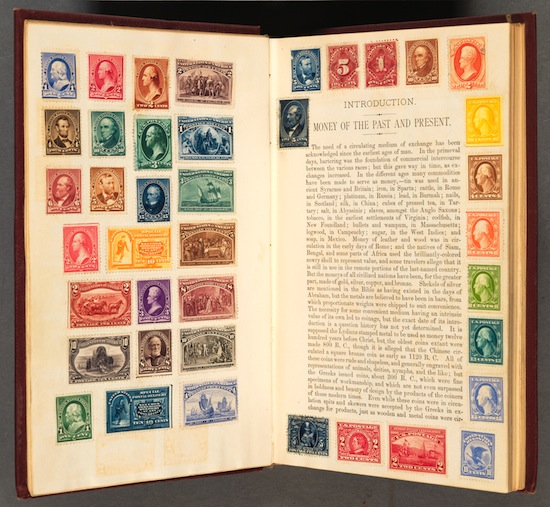

Here’s George Greenlief Evans’ Illustrated History of the United States Mint from 1888, illustrated with stamps. Now you know what to do with your stamp collection.

George Greenlief Evans, Illustrated History of the United States Mint. Philadelphia, 1888. Illustrated by Frederic Rowland Marvin. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

George Greenlief Evans, Illustrated History of the United States Mint. Philadelphia, 1888. Illustrated by Frederic Rowland Marvin. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

But Grangerizing also became a DIY practice, sort of like scrapbooking. Pick up a battered old botany book from the late 19th century, and it’s not uncommon to find a few extra illustrations, some hand-colored, pasted in by a woman of your great-great grandmother’s era. It’s one of those interesting, mostly forgotten domestic arts practiced by women at a time when they were barred from participating in so much of the arts, culture, and scholarship of their day.

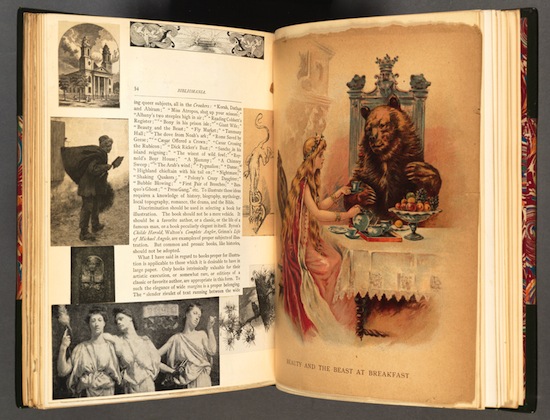

Although this book, Irving Browne’s 1886 Iconoclasm and Whitewash, was Grangerized by the author, it’s very typical of what anyone might have done at home, for entertainment, under the dim light of a gaslight in some dusty parlor.

Irving Browne, Iconoclasm and Whitewash. New York, 1886. Illustrated by the author. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

Irving Browne, Iconoclasm and Whitewash. New York, 1886. Illustrated by the author. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

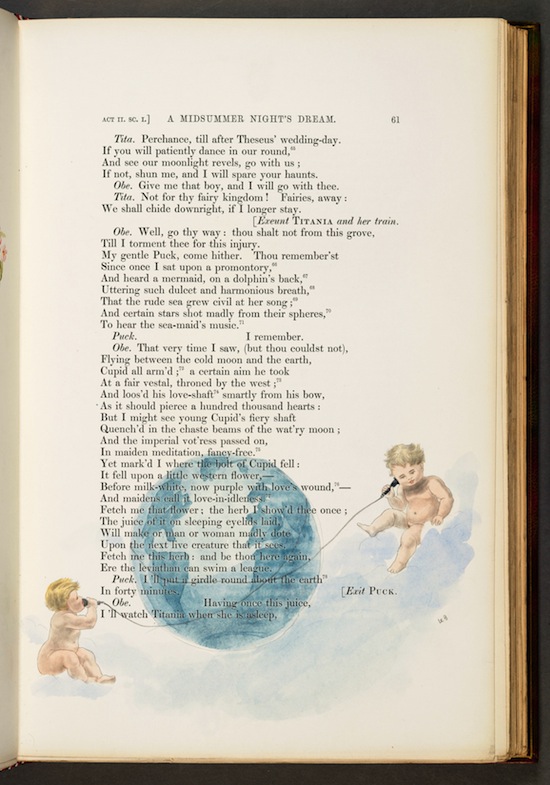

And of course, an extra-illustrated book can simply be illustrated right on the page, as C. Arthur Le Boutillier did for this volume of Shakespeare’s Works, published 1853-65.

William Shakespeare, Works. London, 1853-65. Illustrated by C. Arthur Le Boutillier. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

William Shakespeare, Works. London, 1853-65. Illustrated by C. Arthur Le Boutillier. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

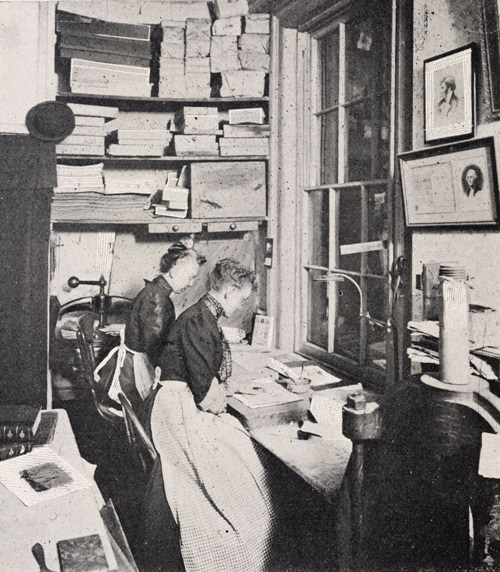

Some people made their living as Grangerites: Here are sisters Carrie and Sophie Lawrence practicing their art at their New York studio.

Sisters Carrie and Sophie Lawrence extra-illustrating a book in their New York City workshop, ca. 1902. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

Sisters Carrie and Sophie Lawrence extra-illustrating a book in their New York City workshop, ca. 1902. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

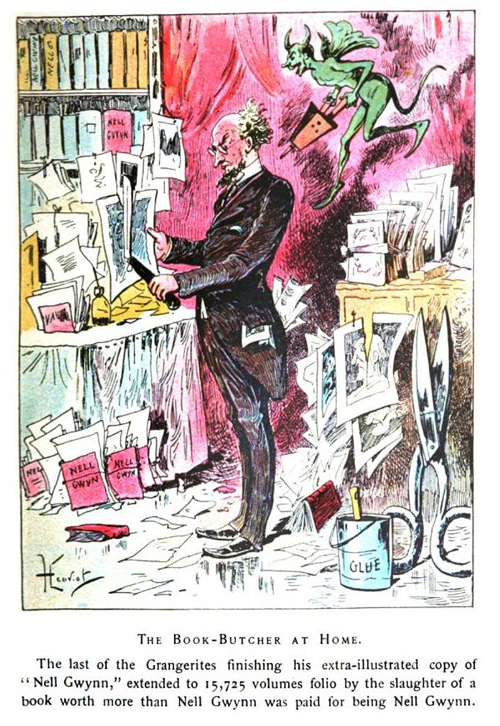

But the practice of Grangerizing, or extra-illustrating, wasn’t universally loved. Around the turn of the last century, it faced quite a backlash, as perfectly good books were pilloried for their prints and modest single volumes expanded to sets of eight or ten to accommodate all the prints injudiciously thrown in. In 1893, the Book Lover’s Almanac criticized the practice, calling Grangerites “knights of the shears and paste jars” and pointing out the folly of “crowding a Bible or a Shakespeare with engravings by the thousands in sets of dreary uniformity as long as your arm.” They called this type of unimaginative extra-illustration “a delusion and a snare, and a weariness to the flesh.” They illustrated the shears-and-paste set this way:

Even children did it: There’s an edition of Longfellow illustrated by Bernarda Bryson Shahn (wife of artist Ben Shahn) when she was ten years old. (This copy’s for sale—you can own it!)

It’s a quaint and forgotten art, but the fact is that there’s something magical about an extra-illustrated book. It’s entirely unique: there’s not another edition like it, anywhere in the world. It has a hand-crafted aspect to it that makes a mass-produced book more personal. And of course, a little of the owner’s personality shows through in the choices about what to paste in, what to illustrate, what to annotate, and what to leave untouched.

In a nod to the tradition of Grangerized books, she’s created an extra-illustrated edition of her novel GIRL WAITS WITH GUN, and is giving it away through a contest on her website.