The Long Golden Age of Useless, American Crap

Wendy Woloson Outlines a History of Our Glorified Junk

Americans have surrounded themselves with crappy things: consumer goods that are typically low priced, poorly made, composed of inferior materials, lacking in meaningful purpose, and not meant to last. Such crap has insinuated itself into just about every aspect of daily life, filling countless kitchen “junk” drawers and clotting garages and basements across the nation. So ubiquitous, crap is nearly invisible, like white noise in material form.

Crappiness is not just a material condition but a cultural one as well: an often exuberant and wholly unapologetic expression of American excess and waste. Crap’s creep into daily life might seem like a new thing, but it began centuries ago. Over time, Americans have decided—as individuals, as members of groups, and as a society—to embrace not just materialism itself but materialism with a certain shoddy complexion.

Living in a world of crap was not inevitable. But for various reasons, Americans forged consuming habits that are now ingrained in the nation’s very DNA. In an age of material surfeit, we continue to spend money on things we do not need, often will not use, and likely do not even want.

One of my favorite Twilight Zone episodes depicts the dynamic of crap better than almost anything else. In “One for the Angels,” affable street seller Lou Bookman tries to distract Mr. Death from taking the soul of a beloved neighborhood girl by giving him the sales pitch of a lifetime. Bookman draws Mr. Death’s attention to an array of goods that he brings forth from his traveling case, like a magician pulling rabbits out of a hat.

Thanks to Lou’s persuasive skills, Mr. Death, at first an aloof and skeptical customer, becomes utterly entranced. The peddler’s neckties are made not of polyester but rather “the most exciting invention since atomic energy,” a fabric that would “even mystify the ancient Chinese silk manufacturers.” His sewing thread is even more enthralling: “a demonstration of tensile strength . . . as strong as steel yet as fragile and delicate as Shantung silk . . . smuggled in by Oriental birds specially trained for ocean travel each carrying a minute quantity in a small satchel underneath their ruby throats. It takes 832 crossings,” Bookman exhorts, “to supply enough thread to go around one spool.” Bedazzled, Mr. Death frantically rifles his pockets for cash, shouting, “I’ll take all you have!”

Like Mr. Death, Americans have approached the marketplace of goods with a combination of world-weariness and openmouthed credulity. The promise of endless supplies of new things, ever cheap and accessible, has captivated and enchanted. And the risk is low, since any one thing doesn’t seem to cost all that much. Yet the result is a material world of ephemeral, disposable, and largely meaningless goods. It is a world of crap, and it has very real costs, ranging from the material to the mental, the environmental to the emotional.

Inferior things became desirable for probably as many reasons as there were people to buy them, including sheer accessibility and affordability.The encrappification of America dates back centuries. While there were, undoubtedly, once village blacksmiths who forged brittle nails, farm women who adulterated their butter, and tailors who cut corners, these were the exceptions. Most things were made by skilled and reputable hands working with good intentions, supplying the needs of people within local communities. The consumer revolution, which began in the mid-1700s, changed all that.

Responding to the increasing demands of farther-flung and more anonymous and democratized markets, cabinet-makers contrived faux finishes to simulate exotic woods and intricate inlays, metalsmiths discovered how to make plated and imitation wares, and jewelers began creating glittering gemstones made of “paste” backed with foils. Even then, however, ersatz goods were still only accessible to the elite and fortunate strivers because they still had to be crafted by hand. And these items were often prized because they were clever simulations, allowing people to purchase more than they truly needed and to show material excess off to others.

But crappy goods—inartful and deceptive simulations, shoddily made and not meant to last—followed very quickly. Inferior things became desirable for probably as many reasons as there were people to buy them, including sheer accessibility and affordability, the desire to emulate friends and impress neighbors, and a simple thirst for novelty. Crappy goods would not have become popular, however, without the countless slick-tongued persuaders who helped sell them. These early pitchmen, as essential to the rise of the nation as yeoman farmers and independent artisans, descended from a long line of itinerant salesmen who, by the late 18th century if not earlier, were pulling beguiling things from their packs with showmen’s flourishes.

Though they’ve long vanished from the commercial landscape, their legacies nevertheless remain. The siren songs promising untold treasures at bargain prices call to us from the jumbled stock of dollar store shelves, the seemingly infinite listings on sites like eBay, countless infomercials, and, once, the Lou Bookmans and Willy Lomans pounding the pavement looking for their next opportunity to make a pitch.

As soon as Americans could get their hands on cheap stuff—often aided by all those roving peddlers and pitchmen—they began encrappifying their lives, tentatively at first, and then with gusto. Not long after the American Revolution domestic markets became inundated with goods from overseas. Great Britain dumped the majority of these items on America’s shores, and many of them were inferior in some way: remainders; damaged goods and knock-offs; the unfashionable and outmoded; things dyed with fast-fading “fugitive” colors and constructed with less durable materials; myriad items that had little purpose and likely would not last.

None of that mattered. After domestic boycotts and periodic embargoes, Americans of all sorts—rich and middling, urban and rural—not only had access to new markets but came to see themselves as consumers as much as producers. By the early decades of the 19th century, retailers advertising bargain wares and shops specializing in cheap variety goods began appearing in large cities and small towns alike.

There were profits to be made in selling cheap goods. Precursors to our dollar stores, they offered the beguiling combination of great variety and low prices. Aiding these retailers were the countless itinerant peddlers who introduced their Yankee notions—and the cosmopolitan ideas they embodied—to the hinterlands. For the first time, American consumers began to value cheaper, ephemeral objects over more durable ones, enamored by the low cost and pulsing abundance of these new goods and the material and emotional satisfactions they seemed to promise.

Americans quickly came to enjoy the cyclical churning of cheap possessions, avoiding long-term commitments to fewer, better-quality, and more expensive things. America’s unapologetically disposable culture has its roots in this era and with these goods.

There is something to be said for the embrace of cheap things over time. Such material access has enabled American consumers to fully participate in the marketplace—not simply the world of goods but the ideas and possibilities they represent. Too, the taste for cheap goods boosted the output of manufacturers, thereby helping to raise the general standard of living. Producers were able to employ more workers to make their wares, wholesalers expanded networks to distribute them, retailers could hire more clerks to sell them, and so on.

Facilitating access to cheap goods also helped spur the government to invest in infrastructure. Networks of turnpikes, canals, and railroad lines not only connected people to once-distant markets but also made possible new ways of doing business, like the mail order enterprises of Sears, Roebuck and Montgomery Ward. On a more personal level, the vast majority of American consumers could embrace novelty for its own sake and for the pleasures it provided, since they no longer had to make do with just a few things that would have to last a lifetime.

This lessened the burdens of ownership itself: now easily discarded and just as easily replaced, possessions no longer had to be painstakingly cared for. The marketplace of crap turned a broken kettle or cracked dish from a crisis into a mere inconvenience effortlessly—and pleasurably—ameliorated by a new purchase.

Long before Cracker Jack tokens and cereal box prizes, merchandisers were rewarding loyal customers with giveaways and prizes.Cheap goods made people’s lives easier in other ways, too. The number of gadgets—from combination corn grinders to miracle fire extinguishers—began increasing in the 1840s and exponentially so after the Civil War, supplementing reliable and familiar tools. Gadgets embodied the seemingly limitless creativity of American ingenuity and drive toward greater efficiency. “New-fangled” devices offered faster, easier, more enjoyable processes for doing everything from washing clothes to peeling apples. But that wasn’t all. Gadgets came to seem like personal servants, promising to turn the burdens of work into entertaining leisure activities.

People could now, all by themselves, make magic happen, whether instantaneously rejuvenating their skin or transforming ordinary potatoes into perfectly julienned strips with the simple turn of a crank. At relatively low cost, gadgets—from yesterday’s all-in-one tools to today’s miracle garden hoers—have delivered outsized wonders and spectacles matched only by their extreme functionality.

More alluring still is the crap that isn’t just cheap but free. Since the first decades of the 19th century, long before Cracker Jack tokens and cereal box prizes, merchandisers were rewarding loyal customers with giveaways and prizes. Even the most pedestrian of things—fly swatters, calendars, ballpoint pens—have helped kindle warm feelings between sellers and buyers, creating loyalty. While today it manifests in items such as t-shirts and tote bags, 19th-century commercial goodwill came in the form of things like calendars, embossed rulers, and cheap jewelry. All of it was crap, but it was free crap, which was all that mattered.

Crappy stuff has also enlivened American homes. Early itinerant peddlers selling cheap plaster figurines helped democratize the trade in bric-a-brac, knickknacks, and tchotchkes. Ornamental wares could now be enjoyed by rich and poor alike. Although they lived in “filthy, damp and dismal conditions,” 19th-century tenement dwellers, for instance, nevertheless were able to “crowd” their mantelpieces with cheap figurines.

However crappy, such knickknacks did not simply adorn people’s homes but offered them brief mental respite from their straitened circumstances. Sometimes, too, cheap imitations were in some ways superior: artificial plants and fruits, whether plastic or plaster, and even if “laughably clumsy, and daubed over with green and yellow paint,” could be more vibrant than the real thing and lasted forever, defying decay and death.

The growing trade in “giftware”—upscale tchotchkes—enabled Americans to expand their decorative horizons even more broadly and boldly. Sold in specialty boutiques, these affordable items—blown-glass art vases, carved wood figurines, hand-dipped candles—allowed their owners to make more nuanced statements about themselves, their tastes, and even their politics. Gift shops began appearing in America at the dawn of the 20th century, serving the rising number of leisure travelers who took cross-country tours in their new automobiles.

These independent shops, often owned by women, offered customers seemingly unique merchandise—Irish linen tea towels, ashtrays crafted in India, hand-painted woodenware napkin holders. Over time, the number of gift shops expanded, enabling ever more consumers to purchase special things that seemed to be imbued with their own personalities, life histories, and individual marks of artistry. But because it has always been mass-produced, giftware can only be derivative and never unique. Its appropriated stylistic glosses, often described as “looks,” such as Colonial Revival, rustic, and contemporary, can only embody a faux authenticity.

Another way that Americans have been able to keenly demonstrate their connoisseurship, taste, and status has been through mass-produced and -marketed collectibles. Produced specifically to be collected, “intentional” collectibles first appeared in the late 19th century, when cutlery companies began making souvenir spoons. But the market really took off in the mid-1950s, when ceramics manufacturers began aggressively marketing commemorative plates. In due course the world of collectibles expanded to include figurines, historical replicas, dolls, and other items that purported to be investment opportunities for increasingly prosperous Americans.

There is no denying that crap has brought different forms of pleasure to people over time.The manufacturers of these myriad objects democratized collecting, which had been a fairly exclusive activity. People afflicted with the collecting bug but of limited means had had few choices: some collected stamps; others, matchbooks and luggage stickers. Serious collecting of serious things—the high-rolling world of antiques auctions, the fine art market, and museum patronage—was a practice both economically and socially out of bounds to all but the very elite.

Intentional collectibles, however, enabled ordinary people to enjoy the thrill of the hunt, the satisfactions of acquisition and curation, the pride of display, the company and camaraderie of like-minded people, and (nominally) the economic benefits of investing. By the 1960s and 1970s, clubs, magazines, and even special market exchanges were serving collectors of everything from Hummel figurines and scale-model replicas of military machines to commemorative coins and limited-edition dolls.

There is no denying that crap has brought different forms of pleasure to people over time. This is probably no truer than when considering novelty goods like Joy Buzzers, Whoopie Cushions, and plastic vomit. These things, too, have long histories: mass merchandisers were selling things like exploding cans of snakes, trick spiders, fake mustaches, Resurrection Plants, and surprise boxes as early as the 1860s.

Americans had never before seen many of these queer and curious things, let alone known what to do with them. But no matter. They seemed to offer untold delights, opportunities, and even mysteries, especially among children and childish-at-heart pranksters.

The nascent novelties market continued to expand, thanks in part to technological innovations that made new things pop and whizz and explode more reliably and in part to the expansion of advertising. Pulp magazines, mail order catalogs, and even bubblegum wrappers had become, in the early 20th century, prime ad space for x-ray spectacles, fake dog poo, and Chinese finger traps. Although the golden age of novelty goods is now long past, for over a century they enabled even young consumers to explore taboo subjects like sex and death by disguising them in frivolous and playful forms.

__________________________________

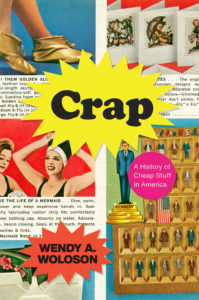

Reprinted with permission from Crap: A History of Cheap Stuff in America by Wendy Woloson, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2020 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved.