The Long Fight to Decolonize Book Research

Kristen Millares Young on Learning from Makah Tradition

I am zipped into a tent on my friend’s beachfront lawn. Caring for her mom and kids, she has a full house, but on this crisp August night, I am glad to be ushered to the cusp of sleep by the churn of the Pacific. I am on Makah Nation land. It is late in a long day spent following my sons, who scootered around the unaccustomed crowds of Makah Days, the tribe’s annual celebration of gaining the right to vote in US elections.

My friend slides open her glass door and shouts into the sea wind. “Do you guys want to try some whale?”

Every single member of my family sits up, sleep forgotten. The boys have heard the story of this year’s whale, a juvenile humpback struck by a non-Native commercial boat in the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Jaw broken, the dead whale was towed ashore by Makahs, including my friend, and butchered for tribal use.

I walk into the house, my husband carrying the boys over the dewy grass, our entire entourage in pajamas. I smile at her mom, who nods and smiles and turns back to the TV, where a newscaster says that no amount of alcohol is safe, a fact that my sons will ask about for months, alongside repeated requests to hear how and why the whale died.

My friend is pan-frying strips of humpback, blood boiling to the surface. I have never eaten whale meat before. I worry about the parasites the blood might contain. “This isn’t how we used to prepare it,” she says. “You’re supposed to soak it in water first. My friend’s making some whale jerky, too. But I couldn’t help myself. I wanted to try a little so I sliced it thin.”

“The word itself, ‘research’, is probably one of the dirtiest words in the indigenous world’s vocabulary.”

Pan-fried humpback both smells and tastes like steak, my favorite when I was a child raised in an intergenerational house like this one. The ways that Makahs take care of their elders reminds me of Latinxs. My friend and I are both amused by the cultural cross-pollination she plates out for my family—tortillas wrapped around sautéed onions, peppers and whale meat.

“Road kill,” some elders scoff, dismissive of meat that was dragged home, already dead, rather than hunted.

I didn’t live in the Pacific Northwest in 1999, when Makah tribal members exercised their treaty rights and, after thousands of hours of physical and spiritual preparation, hunted and killed a gray whale. But it was here, on couches and in kitchens, where I learned to listen for the unsaid.

Stories reveal the teachings the way light casts a shadow. When I read the words of Mukoma Wa Ngugi—“The work of decolonization is as personal as it is political”—I think back to the ways I was conditioned to consider Native peoples through the prisms of federal policies and popular culture. I didn’t believe what I had been told in textbooks and movies, but I didn’t yet know how to link historical genocide to contemporary oppression, nor that they are one and the same.

“The word itself, ‘research’, is probably one of the dirtiest words in the indigenous world’s vocabulary. When mentioned in many indigenous contexts, it stirs up silence, it conjures up bad memories, it raises a smile that is knowing and distrustful,” wrote Linda Tuhiwai Smith (Ngati Awa and Ngati Porou) in Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples.

There are good and terrible reasons for that suspicion. Phrenology—the literal measurement of skull size to confirm theories designed to prove the intelligence of white colonizers—is but a few generations removed. “The ways in which scientific research is implicated in the worst excesses of colonialism remains a powerful remembered history for many of the world’s colonized peoples,” wrote Smith. “It is a history that still offends the deepest sense of our humanity.”

Growing up in a house run by Cuban exiles, I have long been fascinated by how people attempt to exercise personal agency over coerced assimilation into an oppressive structure. In these disunited states, containing within them many sovereign nations, we are in what Biodun Jeyifo called “arrested decolonization.” Every immigrant to this nation becomes a settler upon arrival. I’m drawn to the lies we believe and are told to hasten or counteract our loss of cultural identity. These explorations are my American inheritance.

My own family skipped across three countries in as many generations. We could not afford to stay in our small towns. Not in Spain. Not in Cuba. And, for me personally, not in Florida, hence my home in Seattle. In the Pacific Northwest, I encountered the strength and presence of modern indigenous governance and became curious about these enduring peoples. Raised in diaspora, I wanted to know what it was like to belong somewhere specific.

Growing up, while my mother wrote policies and gave speeches in flawless English she learned by watching television as a teenager, my abuela bustled around the house, sweeping the carpets and handwashing dishes in a rubber tray she emptied, with trembling arms, into the garden. Weeks later, a green pepper might grow from a discarded seed, and the joy it brought Abuela was undimmed with time. Our family owned a vacuum cleaner and a dishwasher that she refused to use.

We have what we have because of our personal industry, I was taught. Hard work is the answer, I was taught. Focus on your own trajectory and be frugal, I was taught.

And, perhaps to make me believe I could succeed in a country that doesn’t always want its immigrants, I was taught to disregard systemic persecution in favor of individual effort. Of the peoples who preceded us, I was taught nothing.

For years I examined layers—documents, oral testimonies, artifacts, the random stuff people keep—and in my book, I tried hard to get it right, knowing most efforts fail.

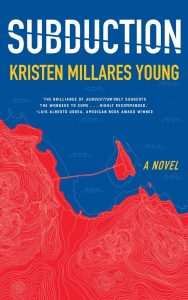

Through the two protagonists of my novel Subduction, set on Makah land, I studied how we tell stories—in particular, what we tell ourselves about ourselves when no one else is listening. Upon these narratives, we build our identities. From those identities, we envision our communities and their attendant constellations of sacred responsibilities.

After researching the recurrent history of anthropological disturbance of Makah territory, I wrote a novel to explore contact, nothing less than the long story of living. Worried about the fractals of oppression spreading like frost over history, for years I examined layers—documents, oral testimonies, artifacts, the random stuff people keep—and in my book, I tried hard to get it right, knowing most efforts fail. But never to have risked engagement feels like a bigger failure, one I’ve seen replicated too often.

I began studying their story only 15 years ago, a lengthy time in the life of a writer but a short window into the world of a people. Taught to keep moving, I learned how to be still, how to quiet myself down and hear the deep wisdoms delivered piecemeal during commercial breaks.

When my belly is full of whale fajitas, my friend tells me a story.

That morning, while I and my family were driving the long hours from Seattle to Neah Bay, she and her friends worked on the whale for hours, cutting strips of blubber and butchering the meat for other tribal members. “When you’re cutting whale blubber, it’s important to have a sharp knife. One young mother, her child strapped to her body, sharpened knives for us all day,” my friend says. “She’d never done it before, but she worked non-stop with her baby on her back.”

Her image echoes across millennia of traditional practice for the Makahs, who have sustained their culture despite federal attempts to exterminate their way of being from this earth.

Resilience is a quality cultivated under duress, over time and against the odds. In diaspora, I learned to appreciate sacrifice and endurance from watching my own family, but our methods of survival required displacement of the community bonds which allowed that mother to flourish. To grow in place could be a far greater thing. For that, the immigrants to this country must recognize on whose land we stand.

__________________________________

Subduction by Kristen Millares Young is available via Red Hen Press.

Kristen Millares Young

Kristen Millares Young is the author of Subduction, named a staff pick by The Paris Review and called an “utterly unique and important first novel” by Ms. Magazine and a “lyrical and atmospheric debut” by Kirkus Reviews. A prize-winning journalist and essayist, Kristen is Prose Writer-in-Residence at Hugo House. Her reviews, essays and investigations appear in the Washington Post, The Guardian, and elsewhere, as well as the anthologies Latina Outsiders: Remaking Latina Identity and Pie & Whiskey, a New York Times New & Notable Book. She was the researcher for The New York Times team that produced “Snow Fall,” which won a Pulitzer Prize. From 2016 to 2019, she served as board chair of InvestigateWest, a nonprofit newsroom she co-founded to protect vulnerable peoples and places of the Pacific Northwest.