The Long and the Short of It: Hilma Wolitzer on Returning to Short Fiction in Her 90s

“To publish a collection of short stories in my 90’s seems miraculous to me.”

When I was a child and asked for a bedtime story, my weary mother sometimes recited:

I’ll tell you a story about Jack A Nory

And now my story’s begun.

I’ll tell you another about his brother

And now my story is done.

Of course I knew that I was being played, and when I protested, my father was enlisted to fill in. But as he lay at the foot of my bed, telling me once again about Little Red Riding Hood or Goldilocks and the Three Bears, he often fell asleep in mid-sentence. I would kick him awake and demand to know what happened next. Although I knew those fairy tales by heart, I couldn’t shake the expectation that this time things might end differently. Maybe the wolf would eat Red Riding Hood instead of her grandmother. Maybe the bears would adopt Goldilocks and they would all live together happily ever after.

I believe it was this curiosity that led to my lifelong passion for reading, and to my career as a writer. It’s not surprising, after those early threats to instant gratification, that I began by writing short stories. Other factors weighed in, too. I was in my thirties by then and busy raising a family; there was hardly any time for an extended narrative. I wanted to find out and to say what happened next—how things turned out—before I was distracted by a needy child or a hissing teakettle.

But it wasn’t merely a matter of enough time to write. Despite the shining examples of writers such as Chekov and Alice Munro, I believed that the short story was my creative adolescence, or apprenticeship, and the novel would be my maturity. I was a late bloomer and a slow learner. But I was also ambitious. When the editor of a literary magazine in which a couple of my stories had appeared inquired if I were writing a novel, I decided to try to do it.

After I developed the habit of writing novels, I seemed to have forgotten how to write short stories, as if I’d made a pact with a literary devil.

After several false starts, I discovered, with editorial help, that a novel wasn’t simply longer than a story. It began to seem wider to me, more encompassing. Even peripheral characters came more sharply into focus. Plot threads could dangle for a while before being tied together, and every chapter didn’t have to end on an epiphany. I realized, too, that it wasn’t necessary for a novel to follow four generations of a family through decades. Virginia Woolf’s novel Mrs. Dalloway takes place in a single day, and some of Alice Munro’s short stories cover entire lives. There were no rules, or if there were any, they were made to be broken.

Once I got the hang of it, I wrote several novels, and there was much to savor while delaying gratification. I woke up each morning with the now familiar characters living in my head, waiting for me to record their latest exploits. My novels were being published and reviewed, sometimes favorably! And for long periods I didn’t have to keep starting from scratch.

But after I developed the habit of writing novels, I seemed to have forgotten how to write short stories, as if I’d made a pact with a literary devil. I read poetry for its lessons of musicality and economy, and I was still reading stories with intense pleasure, but I couldn’t compose one.

Then Covid-19 came. At the beginning of the pandemic, my husband and I were both hospitalized with the virus, and he succumbed to it. Afterward, our younger daughter came up with the idea of collecting my short stories in a volume. I was feeling too sad and too sick, at first, to consider it. But as time went on, I realized that I needed something to do, besides grieve, and something to look forward to. So I began to look at those old stories and arrange them in some kind of order.

Once the collection had been accepted for publication, it seemed slim to me, and missing an element I couldn’t identify. Several of the stories were about a couple who were not my husband and me, but could have been contemporaries of ours. Now they were like neighbors who had moved away, and my old curiosity kicked in. I wondered what had happened to them. And I also felt the need to put down what had happened to us. So, “The Great Escape,” the final story in the collection, and the most autobiographical one I’d ever written, began to take shape. It’s a Covid story, but it’s also the story of a long marriage, and it all takes place in just a handful of pages.

In his essay “Why I Write Short Stories,” John Cheever, whose work—long and short—I love, says

To publish a definitive collection of short stories in one’s late 60s seems to me, as an American writer, a traditional and a dignified occasion, eclipsed in no way by the fact that a great many of the stories in my current collection were written in my underwear.

To publish a collection of short stories in my 90s seems miraculous to me. Many of them were written in my underwear, or my nightgown, and except for the last one, they were also all written in my (relative) youth, when I fervently wanted to know, as I still do, what happens next.

______________________________________________________________

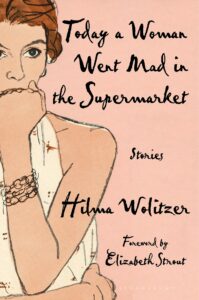

Today a Woman Went Mad in the Supermarket by Hilma Wolitzer is available now via Bloomsbury.

Hilma Wolitzer

Hilma Wolitzer is a recipient of Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts fellowships, an American Academy of Arts and Letters Award in Literature, and a Barnes & Noble Writers for Writers Award. She has taught at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, New York University, Columbia University, and the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference.