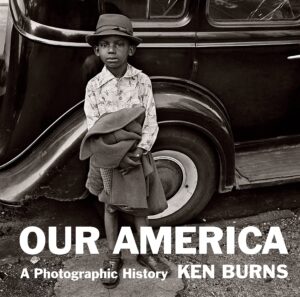

I’ve needed forty-five years of telling stories in American history, of diving deep into lives and moments, places and huge events, to accrue the visual vocabulary to embark on my book, Our America. I knew it would need to reflect all the films I had made; it would need to touch every corner of this country (indeed, every state of our union is represented here); and it would need to engage all of the big themes and small quotidian moments that characterized first Jerry’s approach to taking and looking at photographs, and now the arc of the collective narratives of my films.

It would need to insistently acknowledge in its pages the history of the U.S., but also the story of “us,” the two-letter, lowercase plural pronoun that in its intimacy often balances out the majesty, the complexity, the contradictions, and the controversy of its larger counterpart. I have had the great privilege and responsibility of operating in that special space between the U.S. and “us” for decades—and if I have learned one thing, it is that there is only “us,” no “them.” The photographs would need to try to reconcile these disparate energies.

As Susanna Steisel, and later Brian Lee, and I worked to select and match the images for the book, we were amazed at all the emotions and ideas about our larger national story that were inspired by each of the photographs you are about to experience. Here is our genius, our carelessness, our sensuality, our hypocrisy, our symmetry, our folly, our courage, our absurdity, our faith, our ugliness, our wonder, our irony, our ingenuity, and our cruelty.

Here is our authenticity, our sacrifice, our playfulness, our curiosity, and our grief. Here is our beauty, fragility, grandeur, and cool. Here is reflection and perseverance, industry and Nature. Our harmony and our dissonance. Our forgetfulness and our memory.

Memory permits us all to have an authentic relationship to our national narrative.Accumulated memory at its most intimate level is that deeply personal affirmation of self, that which calibrates and triangulates our sense of who we are. And yet memory is also an ambassador of our own individual “foreign policy”—the agency that helps cement friendships, associations, and ambitions. In a larger sense, memory permits us all to have an authentic relationship to our national narrative. These discrete stories and moments, anecdotes and memories, become the building blocks of our collective experience alongside our individual identities. Out of these connections we find the material, the stuff, the glue, to make our obviously still fragile experiment stick, permanent; “a machine,” someone once said of our constitutional undertaking, “that would go of itself.”

*

Memory is imperfect. But its inherent instability allows our past, which we usually see as fixed, to remain as it actually is: malleable, changing not just as new information emerges but as our own interests, emotions, and inclinations change. I believe that the study of history—particularly a complex and nuanced view of it populated with visual artifacts, like these photographs—can be a table around which all of us can have a personal stake in these past events, the simple moments and grand episodes, where we can have human engagement and try to evoke what Abraham Lincoln called “the better angels of our nature.”

My own work has been an attempt to summon those angels without neglecting the difficult aspects of our national existence. It is our intention, without cloying nostalgia or unforgiving revisionism, to gather up in these images the generous and the greedy, the prurient and the puritan, the sordid and sensational, the hideous and the humorous, the miserable and the miraculous.

In our films, we come across the myriad tensions of our story. Since freedom is at the heart of the American mythology, we straight away encounter an immediate and abiding tension between our personal freedom—what I want—and collective freedom—what we need.

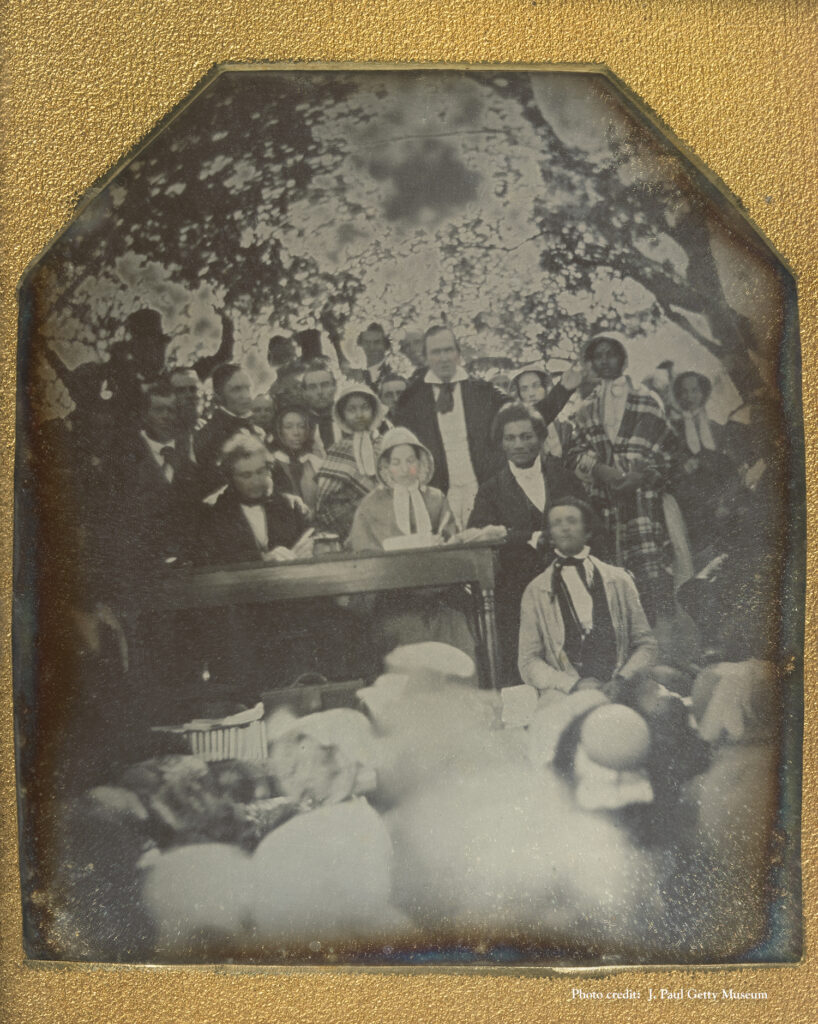

Our country was founded on the belief that all “men” are created equal, yet the man who wrote those words, indeed too many of our exalted Founders, owned other human beings and never saw that glaring contradiction and its attendant hypocrisy. And so race has played a huge, outsize role in our story. There are among us people who have had the peculiar experience of being unfree in a free land, whose history has sadly been relegated to February, our coldest and shortest month, as if it were some politically correct addendum to our national narrative and not, as it is, at the burning center of that narrative. The Black experience in the United States underscores, in ways particular and all-encompassing, our great promise and our great failing. Any attempt to sugarcoat or to bury this central fact of our history is dangerous and un-American.

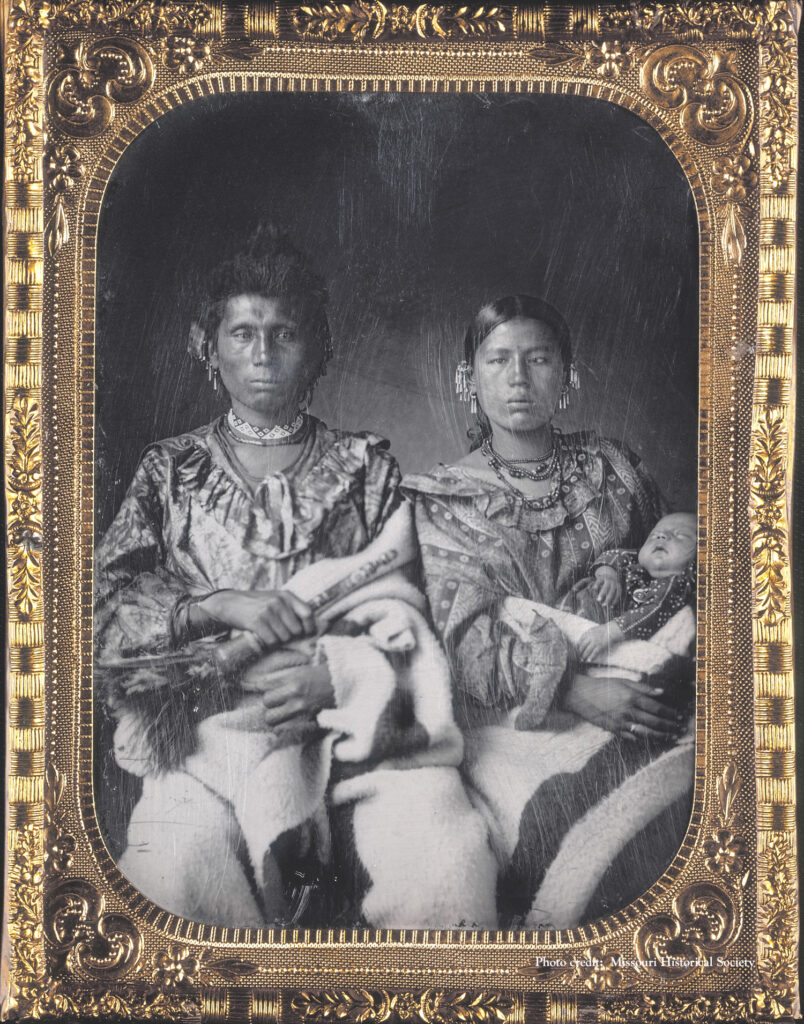

I have had the great privilege and responsibility of operating in that special space between the U.S. and “us” for decades—and if I have learned one thing, it is that there is only “us,” no “them.”Other tensions manifest, as well. We, as Americans, acquired through the ruthless dispossession of Indigenous peoples’ lands an extraordinarily beautiful continent, then proceeded to dam as many rivers as we could, clear-cut as many forests as we could, and mine even the most magnificent of our canyons. And yet we also, for the first time in human history, created national parks, set aside not just for the enjoyment of the rich but for everyone for all time.

We have boasted to the world about our love of liberty—and yet we failed for 144 years of our national existence to extend those basic rights to a majority of our citizens. We have created flying machines and probed the heavens, but have failed to protect the most vulnerable among us. We have, of course, constantly criticized these very failings, overlooking the blessings before us and the natural and human beauty right before our eyes.

These photographs attempt to embrace these contradictions. I take exception to an automatic assumption of American exceptionalism, but we do find much that is exceptional in these images, much to celebrate, even smile at, glimmers of light amid the dark and perilous divisions that threaten still to overtake us.

We are fond of saying that history repeats itself. It never does, of course. No event has ever happened twice. Mark Twain is supposed to have suggested that “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes.” If he did in fact say that, he was right. The Book of Ecclesiastes, from the Old Testament, says this: “What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.” However disappointing or reassuring these words may be, human nature doesn’t change; it superimposes itself on the seemingly random chaos of events. In this way, we see recurring issues, motifs, echoes, resonances—rhymes, Twain would say—in our present moment that seem to mirror the themes of our historical investigations.

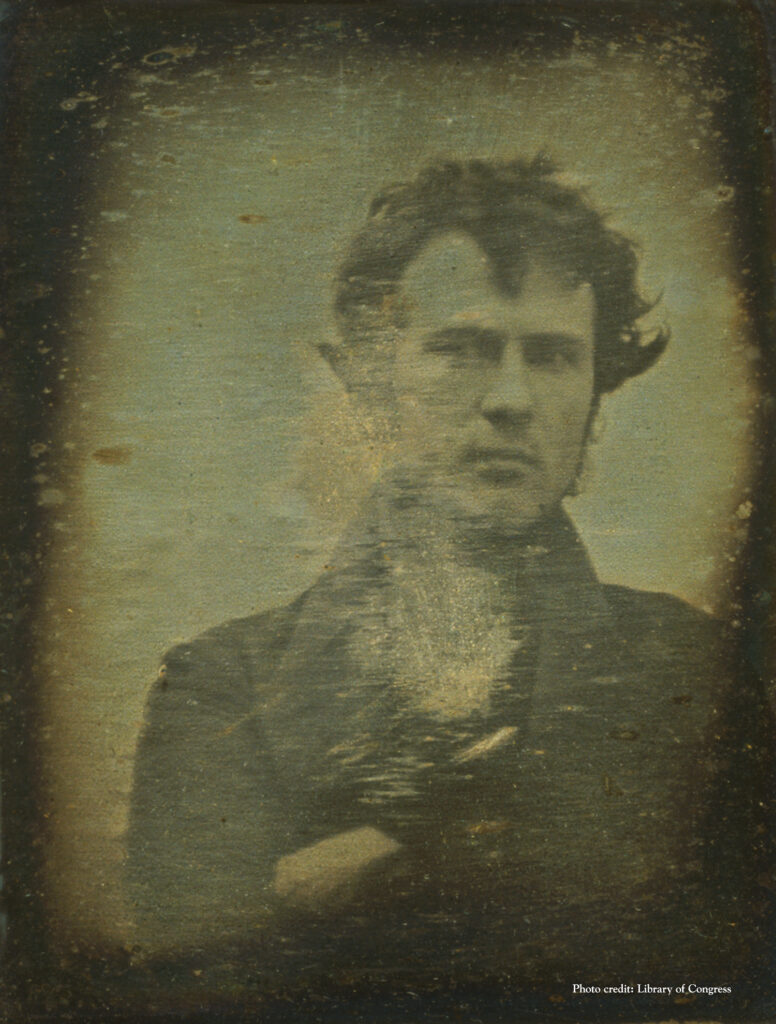

There is selfishness and generosity, scandal and rectitude, altruism and animosity. Rhymes of race, freedom, innovation, politics, war, leadership, prejudice, art, and scandal recur vividly and insistently. The scholar will interpret these manifestations dispassionately; the artist will extract the poetic. The following photographs listen to and amplify these rhymes within specific images, between them, and in their totality. They begin with the advent of photography itself in 1839 and end, more impressionistically, in the historical “no man’s land” of our recent past—all history needs the perspective the passage of time permits—approaching but not quite touching our present moment.

We have created flying machines and probed the heavens, but have failed to protect the most vulnerable among us.My book is entitled Our America, and it was conceived and created in the spirit that assembling photographic evidence of our collective past might help heal our divisions. Of course, this book is really “my” America. We all understand our country differently. There’s no right way to view it, no uniform focal length or perspective. One size cannot, by the very nature of us, fit all. But the poet and painter William Blake thought you could “see the world in a grain of sand.” Our religious teachings suggest “as above, so below.”

The architecture of the atom and the solar system share a similar profound design. So too does my book try to find the specific in panorama and the universal in myriad telling details, a few hundred images to stand in for the billions and billions of photographs that have been taken in our America. It is beyond clichéd to say that a picture is worth a thousand words, but perhaps today—with their ever-increasing number and lack of attention at the time of their taking—the value of a photograph has been diminished. Maybe it’s worth only five hundred words, or two hundred and fifty, or maybe not even one hundred. We have tried here to return something like full value to these images. We hope you will look at each one of them a good long time.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 1839 (Photo credit: Library of Congress)

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 1839 (Photo credit: Library of Congress)

Louis, Missouri 1849 (Photo credit: Missouri Historical Society)

Louis, Missouri 1849 (Photo credit: Missouri Historical Society)

Cazenovia, New York 1850 (Photo credit: J. Paul Getty Museum)

Cazenovia, New York 1850 (Photo credit: J. Paul Getty Museum)

Hanford, California 1914 (Photo credit: Naomi Tagawa courtesy King County Library, Hanford, CA)

Hanford, California 1914 (Photo credit: Naomi Tagawa courtesy King County Library, Hanford, CA)

_____________________________________________

From Our America by Ken Burns, available from Knopf