The Logistical Challenges of a Supersize Acid Test: On the Merry Pranksters’ Trips Festival

John Markoff Details the Publicity Campaign for a Happening

In the fall of 1965, Mike Hagen, one of Kesey’s young Pranksters, arrived at Brand’s place in North Beach and excitedly told him the Pranksters were planning to put together a supersize Acid Test that would eventually be named the Trips Festival. Brand thought it was a great idea. He also knew that the Pranksters were disorganized and that, left to their own devices, they would never make it happen, so he got on the phone and began making calls.

There was already a nascent music scene in San Francisco at the Matrix nightclub, and a group known as the Family Dog had put on some early rock concerts at the Longshoremen’s Hall—a cavernous, six-sided building with a high ceiling—earlier that year. Brand was able to reserve the venue for a January weekend for a $300 down payment on the condition that the hall would be completely cleaned up after each evening’s show.

The immediate challenge was how in the world he was going to advertise his happening. His second call was to Jerry Mander, a partner in Freeman, Mander & Gossage, a high-profile San Francisco ad agency with an office in a converted firehouse near the San Francisco waterfront. Mander and Brand had crossed paths frequently in North Beach, and Mander had watched several performances of America Needs Indians!. He had been impressed when Brand ended the performances by picking up a slide projector and waving it around while chanting wildly, mimicking the sound of a Native American chant he had learned from attending peyote gatherings during his travels in the Southwest.

In Mander’s mind Brand was a pioneer in exploring the new electronic communications and entertainment world that was being touted by Mander’s advertising partner Howard Gossage—a close friend of Marshall McLuhan’s.

“We have something we want to talk to you about,” Brand told Mander, and the advertising exec invited him over. Brand, Kesey, Ramon Sender, and a young man named Ben Jacopetti, who ran an alternative theater group in Berkeley, showed up at the agency a couple of days later, explaining that they had no idea how to market their event.

“I know a guy who knows how to sell tickets,” Mander said. He turned and called Bill Graham.

Graham, a German-born refugee from the Nazis who had grown up in New York City, had come to San Francisco in the early 1960s to be closer to his sister. He had worked briefly as a statistician for Southern Pacific Railroad before going to work as a promoter for the radical theater group the San Francisco Mime Troupe. Mander knew him as an aggressive guy who would drive around town in his Karmann Ghia convertible putting up event posters in bookstores and record shops. Graham showed up, loved the idea, and agreed to come on board.

That was how, several weeks later, while on Christmas vacation from a teaching job she had taken on a reservation in Montana, Lois Jennings would barrel through the financial district as a passenger in Graham’s Karmann Ghia as part of an unsanctioned parade led by the Pranksters during the afternoon before New Year’s Eve. The caravan tossed out handbills as they rolled along. (In San Francisco, getting a parade permit was virtually impossible, but if you kept moving and passing out handbills, it was possible to cause quite a stir while staying one step ahead of the authorities.)

Brand was in full Prankster mode. He maneuvered his VW bus—a sticker on its side read “Love Generator”—through the confetti and toilet paper and old calendars that, per San Francisco tradition, were raining down on the last working day of the year, giving a running commentary from a loudspeaker on top of his bus to the financial district crowd, whom a reporter described as “secretaries and vice presidents and clerks.” When the caravan turned the corner onto Montgomery, Brand’s loudspeaker blared: “You’re urban folkniks. Help us litter up this street. There’s a message for you on each of these snowflakes. Read them. Hey, there’s a pigeon landing on a window up there! What’s wild is we’re all in this parade. It’s all a big trip.”

The group arrived several blocks away in Union Square, where they took out three giant helium balloons with a long cloth banner spelling “N-O-W.” One of the Pranksters, a young woman whose Prankster name was Mountain Girl, spray-painted “Trips” on the balloons, and they were launched into the sky.

Two years later, in 1968, Brand and Jennings would achieve international celebrity when they appeared in the opening pages of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Tom Wolfe’s adrenaline-fueled re-creation of Kesey’s and the Pranksters’ exploits. Wolfe described a mythic figure, the “half-Ottawa Indian” with her hair thrown back, a radiant smile with a jumble of poorly formed teeth. (After being recruited into helping promote the event, Jennings would miss the actual event because she had to return to teach school after the holidays.)

The Pranksters were known for their costumes, and Brand and Jennings had taken to wearing Native American regalia as they went about advertising the upcoming festival. “I remember that we went around to all the hotels with promotional literature for the festival, and the people in the lobby kept saying, ‘Oh, the travel desk is over there,’” Brand would recall later. In a way, they weren’t altogether wrong.

*

There was a series of dress rehearsals for the Trips Festival in December and early January. Bill Graham had organized a benefit for the San Francisco Mime Troupe at the Fillmore Auditorium in December, the night before the Pranksters held the second public Acid Test at Muir Beach. Then the Pranksters held an even larger Acid Test at the Fillmore on January 8. Two thousand people showed up to hear the newly minted Grateful Dead play. At the time, the Fillmore was simply a rundown music venue in a black working-class neighborhood that had been built a half decade after the San Francisco earthquake as a dance hall.

That night, amid all the cacophony, Stewart Brand had an unusual encounter with Neal Cassady. Iconic as the quintessential Beat during the 1950s, Cassady was, like Brand, also a bridge between the Beats and the Hippies. The film documentary The Other One: The Long Strange Trip of Bob Weir documents how Cassady was essential in shaping the Grateful Dead’s worldview and by extension the values of the emerging counterculture. His life captured the free spirit ideal that Brand would later express succinctly in the Whole Earth Epilog: “Stay hungry. Stay foolish.”

Already a larger-than-life character in the fifties, portrayed as Dean Moriarty in Jack Kerouac’s 1957 novel, On the Road, he was the towering figure of the Beat generation. He was twelve years older than Brand, and two years later he would die in Mexico, alone, from a drug overdose after being found comatose on a lonely stretch of railroad tracks on a cold and rainy night.

In the sixties, with Kesey and the Pranksters, Cassady was a speed freak, a wild man, never stopping, speaking in scat verse, carrying a small sledgehammer that he would hypnotically flip in the air over and over. He was the default driver of the Pranksters’ bus, and was known for shifting the gears manically as he drove.

The night Brand and Cassady crossed paths at the Fillmore, among all the chaos, they found a quiet alcove where it was calm. When Brand approached him, Cassady was standing motionless, staring down at the band and the dancers. Brand discovered a Cassady who was not dialing his way wildly through multiple personalities, who was sensible, who was interactive. He was surprised as he realized that there was a “reflective Neal” hidden inside all the time, something other than the manic hipster the Pranksters celebrated. In between the music, the two men chatted quietly. What Brand found was a friendly, thoughtful man who was aware of what was happening.

“It looks like the publicity for your Trips Festival is going pretty well,” Cassady said. It was indeed.

___________________________________________________

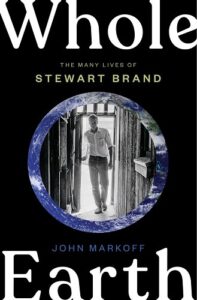

From Whole Earth: The Many Lives of Stewart Brand by John Markoff, published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2022 by John Markoff.