That evening, back in Damascus, I called Ahlam. I suggested a meeting; she named the time and the place.

Nothing more was said over the phone. After that meeting we began working together. She would give me a new way of thinking about war, about what war does, and what it takes to survive. She would become my friend.

I like to work alone, to wander around, look and listen and ask questions, but that is not always possible or wise. Which is when a journalist like me needs a trustworthy guide, someone to act as a go-between, traverse the barriers of language and culture, and gain the trust of people who are unwilling to talk to outsiders. Often the first question put to me by Iraqis in Damascus was—for whom was I spying? They were on the run from strangers who wanted to kill them, so why should they answer questions from a stranger like me?

Given the time it takes to immerse yourself in a culture and do the complex work of observational journalism that requires gathering and cross-checking a complicated array of sources and material, there are few of us compared to reporters covering daily news. And with the collapse of news budgets and the shutting of foreign bureaus in favor of cheaper forms of newsgathering (like, say, not bothering at all), even those are thinner on the ground. To do the work of immersive journalism means being something of a go-between oneself. What I strive to do is bridge the gap between the readers of the magazines I write for, such as Harper’s or The Economist, and people in troubled places who such readers would never otherwise meet. We talk about them, make policies to deal with them, even make war on them, while knowing almost nothing of who they are or what consequences our actions might have.

To write a successful story I have to emerge from the field with an accurate representation of confounding, potentially dangerous situations. Another way of describing immersive journalism is “hanging out journalism,” which can feel a lot like “drowning journalism” or “thrashing around journalism,” especially at the start when I’m getting my bearings. To gain the access and understanding on which this work relies occasionally requires the help of someone informed and connected, whose judgement I trust. In the lingo of journalism, such a person is called a fixer. If a fixer were European or North American, he or she would be called a field producer or a media consultant. A fixer is the local person who makes journalism possible in places where the outsider cannot go alone. Arranging interviews, interpreting, providing context and background, sensing with their fingertips the direction of the winds, fixers are conduits of information and connections. And when they say, “It’s time to leave,” it is always time to leave. Without these local experts, who may be anyone from a doctor with good contacts to a university student with street smarts, most of the news from the world’s dangerous places would not be known, though by the nature of their work, they themselves remain invisible.

“For three days she was beaten, pistol-whipped, and not allowed to sleep, but then her captors began arguing among themselves.”

Fixers are informally contracted, working for a matter of hours to a matter of months, and tend to fade away once the job is done, but they take risks on behalf of the story that even the journalist might not take. Some fixers, in places where a foreigner would not stand much chance of coming back alive, gather the information themselves while the journalist waits at the hotel to type it up. And when the foreign correspondent goes home, the fixer stays behind. “I avoid fixers,” writes the war photographer Teru Kuwayama, “because so many of the ones I’ve worked with are dead now.”

Generally speaking, I avoid them too, preferring to find my own way around. In my Oxford English Dictionary, a fixer is “a person who makes arrangements for other people, especially of an illicit or devious kind.” That is indeed exactly how the Syrian government saw anyone who worked with Western journalists, and why—on a different level—journalists are wary of fixers. Those fixers who are close to a government (or other power structures, such as rebel groups or political parties) may, depending on their allegiances and the incentives involved, turn out to be more like minders, working as double agents without the journalist being aware of the fact. A Syrian working as an “official” fixer, for example, would have to report to the Ministry of Information in Damascus, a ministry with a mandate the opposite of its name. And since a fixer receiving permission to work from the Ministry could earn in a day or two the same two hundred dollars that a Syrian government employee earned in a month, there was incentive to tell the Ministry whatever the Ministry wanted to know.

I had only been there once since I arrived, to the daunting eighth-floor office of the Ministry of Information, to request permission to visit the border. That day I had carefully dressed in what I thought might pass as professorial garb: grey pencil skirt and black French-cuffed shirt, hair pulled back tautly as if I were about to give a lecture on Baudelaire. When the director, a tall and sorrowful-looking man with a reputation for disliking reporters, asked me directly if I was a journalist, I said no. “I’m a professor and a writer.”

If I were to stay below their radar, whoever helped me would have to be below the radar as well. The week I arrived, I had managed to locate two good interpreters: Kuki, a young refugee from Baghdad I’d heard about from a researcher at Refugees International in New York; and Rana, a schoolteacher from Damascus who came recommended by an American radio journalist based in Jordan. Rana was 34 and unmarried, despite (or because of) being attractive and educated. She had turned down many suitors because she didn’t want a controlling husband or a backward one. Though she was studying at night towards a second degree in international law, she still lived with her parents in an apartment where she and four sisters, all university-educated, slept in a single giant bed. “Like kebabs,” Rana said.

That first week I camped at the Damascus apartment of a freelance filmmaker from New York who had sublet me a mattress on her balcony. She was a skinny redhead in her early thirties with a finely calibrated register of anxiety—not a bad quality for a journalist to have unless it tips over the edge. Which it did the morning the air conditioner died.

Admittedly, in the midst of a heat wave, this was a crisis. Standing in the bare-bones kitchen, stirring instant coffee into boiling water and still not quite awake, I listened to her screaming over the phone at her landlord. She wanted him to come over and fix the problem immediately so she was layering it on, simultaneously claiming the malfunction had made her ill, praising the great country of Syria, and alluding to having spoken to “officials” and “police” who all agreed that he had overcharged her on the rent. Of course she wasn’t ill; Syria wasn’t great; and we assiduously avoided officials and police. They considered all foreigners spies, which is how we saw them in return. She had even put a picture of President Bashar al-Assad on the outside of our door, hoping to allay any suspicions about the possible journalistic activities taking place inside. And the rent, though almost as much as she paid for her half of a spacious loft in Brooklyn, was in line with demand: rents in Damascus had suddenly tripled with the arrival of more than a million middle-class Iraqis carrying their life savings in cash.

I’d enjoyed sleeping under the clear moonlit sky on her balcony, lulled by the hum of late-night traffic. But I needed a room, not a balcony, and after much searching I’d found my own place. It was on the fifth floor of a downtown walk-up, since Syrians, the owner wistfully conceded, objected to climbing more than three flights of stairs. Too small for more than one person, it was one of the rare Damascus rentals that didn’t have crowds clamoring to pay whatever the landlord wanted. I was glad to be getting out of the over- heated apartment and away from a roommate who had recently discovered that the pharmacies here didn’t require a doctor’s prescription to give her all the Xanax she needed.

I was going to be on the top floor, above everything, looking down on the city, able to see without being seen, invisible, almost omniscient: a writer’s fantasy. I was going to understand everything that went on, I imagined, and would avoid being caught up in any of it.

Rana and Kuki weren’t fixers: neither had connections or could lead me to sources, though both were game for helping me with whatever I had in mind. Kuki had been an interpreter in Iraq. Not for the army, but for one of the companies that made a fortune supplying overpriced goods to the army. He was young, educated, upper-class, subsisting on money from his parents in Baghdad, a professor and a lawyer whom he’d left behind after a letter arrived on their doorstep threatening to murder the entire family unless their gay son left the country. He came with me on a number of early exploratory interviews and said it made him feel better to see people worse off than he was. Before the war he had been a fashion model in Baghdad—he showed me his portfolio—and he was still vain, refusing to tone down his rock-star attire of tight black T-shirt and white-framed sunglasses even when we were working. Wherever we went, people stared.

One night the two of us went to a bar in the Old City, down tangled alleyways, under a pink neon sign. It was salsa night, hot and smoky, and a steamy, sexy crowd was shouting to be heard. Posters on the wall advertised a visiting European DJ. We drank the pink drinks that came with the cover charge.

I told anyone who asked that I was a professor of fine arts. Or just a “teacher,” if that seemed easier. Kuki said—since he would have liked to be one—that he was a VJ for MTV Lebanon. He was shaggily handsome, skinny as a heroin addict, and could put on a convincing Lebanese accent.

“Do you think anything you write will make a difference?” he asked me at our table looking out over the dance floor, lighting his last cigarette and crumpling the packet.

It was a good question, an existential question, and one I had begun asking myself. I liked to distinguish the work I did from “parachute journalism”—flying in and out and thinking you were an expert when you could have written the same thing without leaving the office—or from the kind of institutional newsgathering that took its cues from press conferences, which meant that whoever gave the press conference wrote the script. But I had been writing long enough to doubt my own contribution. The whole media landscape—so many articles, so much commentary, so much noise—was changing fast, disintegrating. One article, a thousand articles, however in-depth and penetrating, what could they actually do beyond letting me say I had tried?

![]()

George Orwell, in his famous essay “Why I Write,” said that aside from the need to earn a living, there were four great motives to write. The first is sheer egoism: “Desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on the grown-ups who snubbed you in childhood, etc., etc.” The second is aesthetic enthusiasm: the perception of beauty in the world; the desire to share a valuable experience; pleasure in “the firmness of good prose or the rhythm of a good story.” The third and fourth motives interested me most. Historical impulse: “Desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and store them up for the use of posterity.” And finally, political purpose: “Using the word ‘political’ in the widest possible sense. Desire to push the world in a certain direction . . . No book is genuinely free from political bias.” And, thinking about the article I was writing on the refugee crisis, to push the world towards reckoning with the long-term consequences. To show them a human face.

It wasn’t too late to find out a few “true facts”—as opposed to the other kind—and store them up for posterity, but it was too late, at least with the story I was writing, to change the present situations of the people whose lives I was documenting. They might, of course, go on to better days, but there was no question that what was done to them was done. The dead were dead; some people really had been driven mad with grief. Observation, recording, documenting, what difference could that make? If the answer was “nothing,” was I doing it just for selfish reasons: to make myself feel better, less useless, less angry at various injustices? In which case the whole enterprise was not much more than therapy.

“I don’t know,” I told Kuki. Salsa music pounded at my ears. A woman with an Afro was showing the dance floor how it ought to be done. “I think,” Kuki said, blowing a thoughtful smoke ring, “that people are busy.” He knew a fair bit about life in the West and the sort of people who read in-depth analyses in highbrow publications. He had an American boyfriend—they met online—and was trying to get accepted to the United States through the UNHCR. His dream was to live in New York, to become a New Yorker. “You write something, they read it,” he said. “Maybe they feel something. But what do they do about it?”

Then he turned to his favorite subject. “How’s your man?” he asked. “How does he feel about you being away?”

Ahlam and I had been introduced three days before my trip to the border by a Syrian journalist who was on his way to see an Iraqi woman in Damascus’s Little Baghdad—Sayeda Zainab—and invited me along. “She might be interesting for you.”

Ask Syrians what they thought of Little Baghdad and the word “backward” usually came up, or the joke about the two Iraqis expressing their surprise at seeing something unusual: a Syrian! The last time I had gone there my taxi driver, an avuncular man who believed he was dealing with a confused tourist, tried to talk me out of going. “There’s nothing to see there,” he insisted into the rear-view mirror. “Just Iraqis.”

Home to 300,000 refugees, this was where Baghdad had transplanted itself. It was insular, poor and unstable—the Syrian secret police, the mukhabarat, hovered over Little Baghdad the way cops do around high-crime neighborhoods.

“When I caught him staring, he glanced away nervously. If he was a spy he needed to go back to spy school.”

I would love to go with him, I told the journalist that day, but not right then. I was still wearing what I had put on to meet him at his magazine office, a sleeveless shift dress over jeans. This was perfectly fine for the affluent areas of Damascus, which were modern and anything-goes, but not for the sort of outing where I should make an effort to dress modestly and not stand out. Just a glance at my non-Arab face would identify me as a Westerner, so I didn’t bother with a headscarf—I’d had my fill of it in Iran; and in secular Syria even the president’s wife didn’t bother. But when I had time to think ahead I usually wore a wedding ring to visit poor areas, places where marriage was a life event as significant as birth or death. I’d bought the ring for ten dollars at a stand in a shopping mall, preferring to be pitied for having a cheap husband rather than admit that I lived with a man to whom I wasn’t married. Unfortunately, the ring sometimes required me to provide vivid descriptions of my wedding: inventing the dresses the bridesmaids wore, the hall or beach where the celebration took place—usually I opted for the beach. Thinking of this made me realize I hadn’t called home lately. My boyfriend had emailed to say he had tried my number several times but couldn’t get through.

“Don’t worry,” said the journalist, interrupting my thoughts. “We’ll take a taxi to her door.” Outside his office he quickly flagged down a cab on the busy street.

Twenty minutes later we arrived at her apartment. Ahlam opened the door—her husband was out, both kids still at school. Clad in jeans herself, she wore a heart-shaped pendant with a photo of a boy around her neck. Her eldest son, she explained, touching the portrait with one hand. He had died last year.

“In the war?” I asked. Later I would understand how hard it was for her to answer that question.

“Here in Damascus. An accident in hospital.” He had been 11 years old.

As she beckoned me to take a seat, I apologized for my bare arms. She looked at me blankly. She appeared not to have noticed. She offered me a cigarette as if to say: don’t be so uptight.

I’d like to say I knew immediately who she was. That she was the most famous fixer in Damascus. But fixers are never famous—not to anyone except those in the know. They work in murky times and murky places. Which is when and where they are needed. And honestly? She didn’t look the part. Later, because she lost herself in her work in the same way I did, I would sometimes forget how much she had been through to end up here, but that day she gave me a glimpse of something she normally locked up. When she spoke of her son, she looked like someone with a broken heart.

She told me a bit of her story, in fluent English, explaining what had brought her here from Baghdad, and despite how harrowing it was I couldn’t help but admire her attitude. She had a certain flippancy that told me she didn’t care about things other people cared about, that she was her own person living by her own rules. She mentioned that she had worked for the international press in Baghdad, and when I said I was interested in meeting more Iraqis in her neighborhood, she wrote her telephone number in the back of my notebook.

![]()

It was easy to miss the gravel turnoff from the paved highway that had taken me from the chic shops and modern restaurants and office towers of downtown Damascus. The taxi driver had to brake and reverse against traffic. Marking the roundabout on the main street of Little Baghdad— recently renamed Iraqi Street after its residents—was a large folk mural of Hafez al-Assad, who had ruled Syria for three decades, painted in the style of a psychedelic rock poster. Every second shop window displayed a photograph of Assad’s son Bashar, in mustache and aviator sunglasses and army fatigues, an obvious attempt to make him look less like the nerdy ophthalmologist he had been before taking the presidency in 2000 when his father died. Aside from its festoons of electrical wires and its taxis and sputtering motorcycle carts, the neighborhood looked medieval.

Drab low-rise tenements emerged like dead teeth from streets of pounded dirt. The air smelled of roasting meat and baking bread. A mule passed by pulling a cart overloaded with watermelons. At the roadside a bearded man with a wrestler’s build sold cigarettes, his upper half so hale and robust that it took a moment to register that he had no legs. Farther along were the gold shops where Iraqi widows performed alchemy, turning their jewelry into bread; some did the same with their bodies once the gold was gone.

Looming above it all, aloof from the spectacle, was the magnificent shrine to Lady Zainab, granddaughter of the Prophet Mohammed for whom the neighborhood had taken its name. With its turquoise minarets and gilded dome, the shrine was the only good reason for visitors to come here. Zainab is a heroine to the Shia for having stood up against oppression after the seventh-century battle that cemented the Sunni–Shia divide. The split began after the death of the Prophet Mohammed in 632 AD, when there was a dispute over who would take his place. The Shia believed it should be the Prophet’s direct descendant, and the Sunnis believed any upstanding male was electable. After the murder of the Prophet’s closest male relative, Ali, a battle took place on the plains of Karbala in what is now Iraq. Ali’s small band of followers, the shia’tu Ali, were slaughtered, and his daughter Zainab was taken to Damascus in chains. This was known as a Shia area because of the shrine, but now Iraqis of all sects—Sunni, Shia, Christian—lived here side by side as they used to in Baghdad.

It was Ahlam’s suggestion to meet at the main street roundabout. In the warren of nameless alleyways that branched off from it, she figured I wouldn’t be able to find her apartment. I waited under the red canvas awning that shaded an electronics shop, willing myself to look inconspicuous. This wasn’t easy. Westerners never came to this part of the city except in tour groups to visit the shrine. Fat and pale, they filed out of buses with expensive cameras dangling from their necks, blinking like newborns in the stark sunlight.

As I stood there, glancing at my watch, I felt a rising anxiety. Once, when I’d come here before meeting Ahlam, I had been swarmed by a group of Iraqi men. They were out of work. They were running out of money. They were desperate. They were angry. “I have a question for you,” said one of the men, his face inches from mine. “If people come and tell you to get out of your home, if they are killing you based on your identity card, if the international community does nothing—tell me, what will be your destiny?”

I had no answer to give him. The crowd was growing larger, gathering momentum. Crowds like that crave some sort of release, a catalyst, some object on which to vent.

Now, as I stood alone in the shadows beneath the canvas awning, a man walked past. He stopped short to rubberneck, his mouth agape, then took up a post beside me and watched me from the corner of his eye. When I caught him staring, he glanced away nervously. If he was a spy he needed to go back to spy school.

“Like army commanders, sea captains and wilderness explorers, Ahlam’s stubborn fearlessness made those around her feel fearless too.”

I was relieved to see Ahlam crossing the sunlit main street towards me. She was tall for an Iraqi woman. She wore men’s black jeans, men’s black shoes, and a man’s overcoat that defied the oppressive heat—a style she had adopted when the war began and there were bigger problems to worry about than conforming to fashion. Her broad and high-boned face might have been beautiful if she had paid the least attention to vanity. But her face was unusual here because it seemed cheerful, right at home. As if we weren’t walking through a refugee slum where Syrian agents kept watch for rogue journalists and for any sign of the sectarian tinder that might set fire to Syria as it had to Iraq.

Phone in one hand, she greeted me with the standard three kisses—right, left, right—smiling as if our meeting here was the most natural thing in the world. We might have been two friends about to go to lunch. No one seemed to be watching us, but two policemen were standing beside the Assad rock poster directing traffic, their eyes concealed behind mirrored sunglasses. Leading the way to her apartment, Ahlam walked quickly but not as if she were in some kind of hurry. Merely the gait of a busy person. She stopped to talk to a shoeshine boy whose family she knew. Such boys were eyes on the street: useful sources of information.

Walking with her into the maze of yellow dirt alleyways, sweat pooling beneath my clothes, I felt a strange sensation. I felt relaxed. Almost happy. Like army commanders, sea captains and wilderness explorers, Ahlam’s stubborn fearlessness made those around her feel fearless too.

She had come to Damascus after being kidnapped in Baghdad two years ago. The conditions of her release were a $50,000 ransom and a promise to leave Iraq forever. Her family raised the money—her younger brother Salaam sold a car; her sisters and sisters-in-law sold their jewelry; her older brother Samir organized loans to cover the rest. “For the money,” she said, reaching for her cigarettes as we talked in the sweltering heat of her living room, “they let me live.” She came from a thriving Sunni farming village on the northwest edge of Baghdad, and spent the early months of the war working as a fixer for the Wall Street Journal. After that, for the next two years, she had worked at a civil–military affairs office the Americans had built in her district. The General Information Centers (GICs)—the Americans, and anyone else referring to them, pronounced it “gik”—were connected to the Iraqi Assistance Center, which ran humanitarian operations for the US military. Hired as a caseworker on a salary of $450 a month, her job was to translate compensation claims for the families of war victims. A successful claim for someone killed by accident had a maximum payout of $2,500. But the centre, with its all-Iraqi staff, was largely left to its own devices, and since by then she was also a district councillor, she was soon made deputy director, addressing all manner of humanitarian concerns: the wounded, the orphaned, the widowed. A lot of her time was spent locating prisoners who had disappeared into American jails, leaving anxious families who came to her for information on their whereabouts.

Of course it was dangerous to be in any way associated with the Americans, but it was the only way to get anything done. “I had many threats from militias who thought I was a spy.”

First came a petrol bomb, tossed through her bedroom window. She returned from work one day to find her bed charred by fire, all her clothing incinerated. She had hidden her savings in her clothing: no one trusted the banks.

Then came flyers, delivered to the homes of her neighbors, accusing her of being a spy for the Americans. “I didn’t care. I wasn’t a traitor. My aim was to serve my people.”

She ignored the signs until the beginning of 2005, when the head of her district council was murdered. A rumor surfaced that another councillor had also been killed.

Concerned that it might be Ahlam, the Americans sent soldiers to knock on doors throughout her village. “Have you seen this woman?” they asked, showing her photograph to the very people who had been told she was a spy. Returning home from work that day, she felt the eyes of every villager upon her. “Now I was trapped.”

One cold January evening, a week after the murder of the council leader, she was gathering firewood beside the main road of her village. By day she was a professional woman, working 12 to 14 hours, consumed by problems that seemed only to multiply, but outside of work she still had the responsibilities of a wife and mother. Since electricity was no longer reliable and cooking fuel now sold on the black market at outrageous prices, she had to cook for her family over a fire.

As darkness approached, and with it a bitter cold, she bundled twigs and branches into her arms. A car pulled slowly up alongside her and stopped. A black Mercedes with tinted windows. She could not see inside. The driver’s side window lowered just enough for her to hear a man’s voice. “Peace be upon you, sister.” A voice she did not recognize.

“And upon you peace,” she replied.

He tossed a scrap of paper from the window and the car sped away, its tires tearing up the road.

She walked over and picked up the paper. It was a handwritten letter, hastily scrawled. She read it in the dim light.

Peace be upon you, sister. I am someone who knows what you are doing and respects you very much. For your own safety and the safety of your children, you must leave your home tonight.

She dropped the bundle of sticks. She had received threat- ening letters before, and ignored them, but this time was dif- ferent. “I knew I was next.” Gathering her husband and three children, throwing their belongings into the car, she moved to a friend’s home, and from there they crossed the border and made their way to Syria’s capital, Damascus.

She had thought she would stay in Damascus and keep her family safe, but her two older brothers followed her there to relay a message. Her flight, they told her, was being viewed as proof to everyone back home that she was exactly what she had been accused of being—an American spy. She came from a respected family; her father had been the most important man in their community. Their lives depended on those relationships of trust. If she stayed in Syria it would be like admitting she had done something wrong. For the safety of her extended family at home, she must return to Iraq.

Reluctantly, defiantly, she agreed. She left her husband with the children in Damascus and returned on her own. Before she left she bought new black jeans and a pair of new black boots; she decided she would walk with her head high and prove that she was proud and unafraid. When she arrived back in her village, her father-in-law, in lieu of a greeting, listed off the names of all those who had been killed or kidnapped in her absence.

This time she no longer slept at home but lived in her office at the GIC. She had everything she needed—food, a generator, a mattress, guards to watch over her. The Americans even offered her a car and driver, she said, but this she refused: it would be an obvious target. After her car broke down, she relied on her brothers to drive her around, and when they were busy, on taxis. Taking a taxi was Russian roulette, and one bright summer morning in July 2005, flagging a taxi on the street, her luck ran out.

Four cars surrounded her, each with four armed men inside. Who were they? It would take her some time to figure out the answer to that.

“You’re coming with us,” said one of the men. The youngest of them, a boy with a machine gun, looked hardly more than 14. “He wasn’t even old enough to grow a proper mustache,” Ahlam recalled. When he lunged at her, she grabbed him by the collar and shoved him hard against one of the cars. The man standing next to him fired a shot between her feet. “I’ve been tracking you for a year and a half,” he snarled.

“Why didn’t you just call me?” she told him. “I would have come to see you.”

The man didn’t like her attitude one bit. “He shot a bullet beside my right ear. He would have liked to put the bullet in my head, but they only had orders to torture me, not to kill me. He told me he’d already tried to kill me several times but he couldn’t catch me.”

He told her she drove too fast. “I used to drive 160 kilometers an hour on the highway.”

“You were trying to escape them?” I asked.

“No. I just like to drive fast.” She sighed. “I had a Volvo. My dream in life is to have another Volvo.”

The next thing she knew, she was bundled into the passenger seat of one of the cars, a blindfold across her eyes.

“I want to smoke,” she said, her back stiff as a pole. “What?” said the boy. He was sitting behind her in the back seat with his machine gun.

“Give her a cigarette,” said the driver.

The boy had taken her purse. Now he dug through it until he found a pack of cigarettes. “These are American,” he said suspiciously, as if this were proof of her treachery.

“No, they are Korean,” Ahlam told him. Pine cigarettes, her favorite brand, are made in South Korea. “You have to learn how to read.”

She didn’t have time to finish her cigarette. Pulling off the road, the men grabbed her by her feet and shoulders and tossed her into the back of a truck. They changed trucks several more times along the route, tossing her from one to the next. “They were playing soccer with me, like I was the ball.” She was handcuffed, the cuffs so tight on her wrists that her hands swelled, and she shouted until they loosened the bands. She was taken somewhere in the desert. The walls of the building were mud and the floors of sand, the wind so hot it burned her skin. She later heard that her boss at the GIC, an American major named Adam Shilling, had sent a hundred soldiers to look for her.

Her captors began to interrogate her. They tied her to a chair and asked about contractors, military bases, interpreters. “I didn’t have any answers to their questions.”

One of her captors beat her several times a day—“he seemed to be enjoying himself”—but she had the feeling there was some confusion. As if she wasn’t the kind of captive they had been told to expect. They had envisioned some high-value American spy, some sort of Mata Hari, and seemed utterly baffled by a mother from a respected family who had become important enough to have information they wanted. They claimed to have reports that she traveled around in a Humvee, that she was having an affair with an American colonel, that she had dyed her black hair blonde.

“Take off my head cover,” she told them. She’d always covered her hair, it was how she was raised, and since the war began it was a matter of life or death. “See for yourself.” They seemed frightened by the suggestion. Killing her would be a lesser sin in their eyes than seeing her hair. That’s when she knew who they were: al-Qaeda.

For three days she was beaten, pistol-whipped, and not allowed to sleep, but then her captors began arguing among themselves. She could hear them through the walls of her room. The man who beat her argued that she ought to be killed. Another voice, one she had not heard before, agreed. “If I were in your place,” he said, “I would just kill her. If she’s innocent she’ll go to heaven. If not she’ll go to hell.”

Another voice, younger, objecting. Would God not want them to discover the truth?

The younger one asked her tough questions but he never laid a hand on her. He interrogated her extensively about her central crime, working for the Americans, and she tried to convey nuance. She worked with the Americans, yes, but in fact her work was for the orphans and widows who came to her for help, and for the families of prisoners detained by American forces. She knew nothing of military bases, mercenaries, maneuvers.

They shouted at her that this was exactly the sort of thing someone in her position would say. If she was lying, she would pay with her life. “I said my only request was that they don’t throw my body in the river. So my mother wouldn’t wonder if I was alive or dead like many of the families of the disappeared.”

The young interrogator investigated everything she told him. When she told him she had helped rebuild a school, he sent a scout to check on her story. Then he took her phone and called through the numbers it contained one by one. And in the end, in the strange and circular way life sometimes works, it was the testimony of the orphans and widows she had been trying to save that saved her life.

So the feeling I had about her, that she was fearless, was right. She was fearless though she had plenty of reasons to be afraid. Because after she finished telling me this story she told me something else.

“I’ve figured out I’m being watched here in Damascus,” she said. “Maybe by those same people who kidnapped me in Iraq.”

She was wrong about it being the Iraqis, but she was indeed being watched.

__________________________________

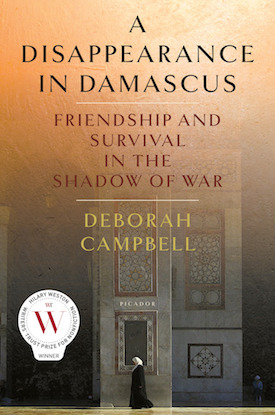

From A Disappearance in Damascus: Friendship and Survival in the Shadow of War, by Deborah Campbell, courtesy Picador. Copyright 2017, Deborah Campbell.