The Last Thing She Wrote

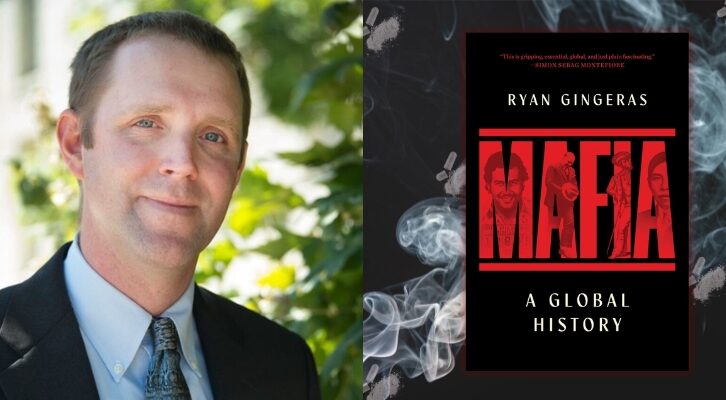

Jason Rosenthal Reflects on the Small Joys of Life With

Amy Krouse Rosenthal

When I first read Amy’s brilliant piece, I was blown away by the prose. I felt humbled that the last project she worked on, literally from her deathbed, was about me and for me. “Well, this is brilliant,” I thought initially. “If it gets published, great. If not, at least Amy had the time to get it done.” It’s part of the life of a writer that it’s impossible to predict how far a completed piece will go, if anywhere. Zero part of me imagined what would happen once her Modern Love column was published in the New York Times.

I recognized the traits from our very private life that Amy wrote about in her essay. We did not need to shout to the heavens how we felt about each other during the course of our long marriage together. We knew it. However, when she got her diagnosis, we began to speak about life after Amy. In those conversations, she encouraged me to carry on, to find someone else, that she wanted happiness and a long life for me with someone new. I was unable to process that reality until much later, so my reaction to her words at that point was always along the lines of “Okay, Amy, thank you. I understand how you feel.” And in typical AKR fashion, she’d say something like “But please wait a few months . . . ,” always infusing the challenges of life with humor.

Reading Amy’s words again is as overwhelming as people’s reaction to the piece when it first came out. It conjures up the emotions from that time, because behind so many of the qualities she comments on, I don’t just see me, I see us. Those memories of cheese and olives, of the mini-sculpture that still sits on my shelf, of the Sunday morning smiley faces . . . those are memories of us. Sure, I did those things, but I did them for Amy. It didn’t strike me until much later that embedded in those memories are seeds that go all the way back to our marriage goals and ideas list. They are parts of me that didn’t emerge fully formed but instead grew out of my love for her and our love for each other.

More than anything, though, the shared DNA here is that drive for “more” that Amy speaks of. In so many ways, that was the essence of our time together, a hunger to be together in whatever way possible.

*

And yet even at the end of her life, there were surprises.

One evening when we were deep in the throes of hospice, I stepped out of the house—a rare event at this point—to make a trip to the grocery store. The store was close to home, so I took the opportunity to get some fresh air and walked there. Our house is located on a tree-lined street on the north side of Chicago, with a brick-paved front area and a black wrought iron picket fence, kind of a modern Tom Sawyer deal.

I was gone for maybe thirty minutes. I walked home in a quiet dusk. Streetlights had just come on. The peace and the beauty gave me a welcome exhale.

Then, as I approached the house, I came to a complete stop and just gaped. I even wondered if I was experiencing some sleep-deprived, stress-induced hallucination. Somehow, in the half hour I’d been gone, someone had tied a row of yellow umbrellas to the 38 or so feet of our fence. They were evenly spaced, open, glistening in the fading dusk. I’d never seen anything like it, not even in a movie or a museum.

I raced into the house, and Paris and I assisted Amy to the front door to see this incredible vision. Depleted and frail as she was, she was still able to marvel at it. She didn’t say a word, she just stood there, with help, her eyes wide, and she smiled.

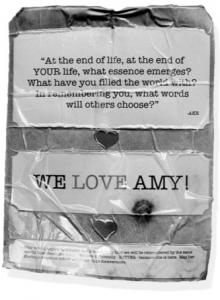

This sign marked the scene I returned to.

This sign marked the scene I returned to.

Possibly the most amazing thing of all—it was done in completely anonymity. No one ever took credit for it. To this day, I have no idea who gave us the gift of that unforgettable work of art.

Whoever you are, “Thank you” doesn’t begin to express it. And thank you, human race, for the goodness that goes unacknowledged far too often.

Looking back, it’s become especially clear to me that much of the generosity that was showered on Amy during this impossibly difficult time was the result of the immeasurable generosity she showered on the rest of us. Somehow, with that frail, dying body, she found the strength to pay attention to everyone close to her—her family and close friends—and give them each a special moment to remember her by and tie her to them forever. A last conversation. A final thought. An assurance that everything would be okay, that she knew death was coming, and that she wasn’t afraid. We all recall how at peace she was with the fact that she’d done everything medically possible and was ready for her transition, and she still found the strength to take care of us, while she was in hospice.

What a gift to have had these moments, and why shouldn’t the rest of us have them now, while we’re still healthy? What are we waiting for? How arrogant of us to believe there will always be “more time.”

__________________________________

From the book My Wife Said You May Want to Marry Me: A Memoir by Jason Rosenthal. Copyright © 2020 by Jason Rosenthal. To be published on April 21, 2020 by Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

Jason Rosenthal

Jason B. Rosenthal is the number one New York Times bestselling author of Dear Boy, cowritten with his daughter, Paris. He is the board chair of the Amy Krouse Rosenthal Foundation, which supports both childhood literacy and research in early detection of ovarian cancer. A lawyer, public speaker, and devoted father of three, he is passionate about helping others find ways to fill their blank spaces as he continues to fill his own. Jason resides in Chicago, a city he is proud to call home.