The Last Poems of Les Murray

From the Famed Australian Poet’s Collection, Continuous Creation

A Note on the Text

“I think I’ve got about three-quarters of a new book ready,” Les Murray told me and my wife, Margaret Connolly, who was Les’s literary agent, on our last visit to the house in Bunyah where he had spent a large part of his life. It was November of 2018, and Les had only five more months to live.

In the years leading up to that day, his literary work had been confronted with a series of obstacles. His old typewriter had broken, and could not be repaired, while a second-hand replacement typewriter sent by a well- meaning friend did not work either. As Les continued to refuse to enter the digital world himself, he had come to rely on his wife, Valerie, to type out his new poems on the computer she had purchased. But Valerie, as a result of an unsuccessful knee replacement operation, was no longer able to walk to her study. Les, too, was almost completely immobile.

In October, he had resigned from his position as Literary Editor of Quadrant magazine after a tenure of more than 30 years. As we spoke with him, that day in November, it became apparent that his usual mental acuity was in decline, so we couldn’t be sure whether or not that new book really existed.

At the end of April in the following year, his long journey came to an end. Then came the complications of probate, and arrangements for a State Memorial, while Valerie had to move into a nursing home. Before we could return to Bunyah, the Covid pandemic arrived, and no one in New South Wales was allowed to travel beyond their immediate neighborhood. Not until October of 2020 did it become possible for us, accompanied by John Vaughan, the Murray family lawyer, to make our way along the gravel road that leads toward the humble wooden structure that once housed the author of the most distinguished body of work produced by any Australian poet.

The garden outside was overgrown and the living areas were chaotic, but the study where Les had written his poems seemed as if he had just left it—the bookshelves clean and well-organized, the desk tidy with writing pads and pens in place, the broken typewriter pushed to one side. In the center of the desk lay a black spring-backed folder, and, just as Les had said, about three-quarters of a book’s worth of poems were inside the folder, all typed out by Valerie. On the floor beside the desk was a large cardboard box, like one of the boxes seen in a removalist’s van, filled to the brim with pieces of paper. The box contained all of the past five years or so of correspondence Les had received, along with multiple handwritten drafts of the finished poems that were in the folder, and further drafts of poems that had not yet been typed out.

There were multiple drafts of these untyped poems, too, and I decided to type out what seemed to me the latest and best versions of these drafts, relying entirely on what Les had written rather than trying to “finish” or edit his words. The last 17 poems in this collection (from “Azolla” onward), as well as the poem “Exile”—which seemed to me a companion piece to “Balz’s Fosterling,” a poem that Les had published internationally in the preceding year—are the result, amounting to roughly a quarter of a book.

When Les was interviewed by The Paris Review, he claimed of his writing methods, “I often don’t have many drafts in handwriting,” but the contents of the box disproved this assertion. Instead, the box was proof of just how meticulous a craftsman Les had been, and of how hard he worked to polish every line, even of those poems that read like spontaneous quips.

Beside the box on the floor, under the desk, were the three massive volumes of the project Les referred to, again in his Paris Review interview, as his hobby: “I collect images, postcards, photos, bits of verse, weird newspaper snippets, labels. They all go into big old-style ledger books to which Clare gave the title ‘The Great Book’, pronounced in Scots.” (Clare is the younger of the two Murray daughters.) Each volume took a decade to compile, and in the latest one can be found the source material for some of the poems I have added to this collection. A somewhat mystifying poem called “The Breast Depot” is clarified by a photo pasted into “The Great Buik,” while the reference to “Clare’s albums” in “On Bushfire Warning Day” becomes self-explanatory.

These ledger books will, in due course, be deposited in a library, providing scholars and interested readers alike with indispensable insight into the mind behind the poetry. The collection of poems in the folder did not have a title, so I have chosen to name it after one of the briefest of them, a title which could be seen as summing up its author’s life’s work.

–Jamie Grant

*

From Continuous Creation

“Testing the Chainsaws”

Cross cut and long cut,

test splits and loud chaw,

dry blade with grit pouring,

blood heaped on the floor.

Up-angled many-severed

black toast-crusty ends

clamped in ring steel.

Crack-faced open lightnings

ham sliced parallel,

fragrant screamy chock burr,

pistol-gripped and urged well.

“Stuart Devlin’s Sculpture”

Modern coins the sizes of shine

swept off my friend’s bureau in Ghent

and pocketed by my careless habit –

not brown pennies too dull to return

they include designer Devlin’s sculpture

of the duckbilled animal

swimming up to the top swirl

and five kangaroo tails mixed to a dollar.

When the Irish attained their republic

they mounted their noble beasts trim

each well inside a knurled rim

and labelled in lapidary Gaelic

while our successors simply enact

themselves: the lyrebird under music,

echidna belly-on like a buckle

each numerally off-center and whacked.

What is the use of small change?

To pay small debts, toss up, delight children,

to gamble by the jingle-crash billion –

to clean your teeth, with the card tasting strange.

__________________________________

Excerpted from CONTINUOUS CREATION: Last Poems by Les Murray. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2022 by Valerie Murray. All rights reserved.

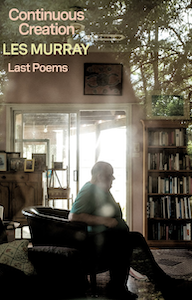

Les Murray

Les Murray (1938–2019) was a widely acclaimed poet, recognized by the National Trust of Australia in 2012 as one of the nation’s “living treasures.” He received the 1996 T. S. Eliot Prize for Subhuman Redneck Poems and was awarded the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry in 1998. He served as literary editor of the Australian journal Quadrant from 1990 to 2018. His other books include Dog Fox Field, Translations from the Natural World, Fredy Neptune: A Novel in Verse, Learning Human: Selected Poems, Conscious and Verbal, Poems the Size of Photographs, and Waiting for the Past. Photo by Peter Solness.