The Language Police Were Terrifyingly Real. My Grandfather Was One.

Martin Puchner on Rotwelsch, an Elusive Language of Central Europe

Our society seems divided between those who want to abolish the police and those who want to abolish the language police. The Left fears people with handcuffs and guns making violent arrests while the Right fears newspaper editors and college teachers canceling offensive words.

While today “the language police” is only a metaphor—no one is actually handcuffing words or arresting their speakers—it hasn’t always been that way. I’ve been researching how generations of police tried to control a forgotten language called Rotwelsch, which I learned about as a boy.

Rotwelsch—which means “beggar’s cant” (in Rotwelsch)—was a language spoken by vagrants on the roads of Central Europe since the Middle Ages. Combining German, Yiddish, and Hebrew, it was incomprehensible to all but initiates, and never written down, a language perpetually on the run.

Associated with vagrancy and criminality, Rotwelsch attracted the attention of the police. Collaborating over centuries, police forces across Centra Europe compiled lists of words and their meanings to decode this jargon of the underground. Their preferred method was to arrest its speakers and force them to divulge their secret way of talking. In the case of this language, at least, the police with handcuffs and the language police were one and the same.

The study of Rotwelsch took a darker turn in the early 20th century, when it was swept up in a wave of anti-Semitism.

The first person to gather and study the archives on Rotwelsch was an unusual policeman by the name of Friedrich Christian Benedict Avé-Lallemant (1809–1892). Living at a time when the first modern police forces began emerging, he analyzed the influence of the social environment on crime, attacked the criminal justice system as antiquated, and argued for prison reform.

It was in the course of these efforts that Avé-Lallemant came across Rotwelsch. He noticed that these itinerants were adept at shmusen, a word borrowed from the Yiddish shmooze, “to converse,” but among Rotwelsch speakers it meant speaking Rotwelsch. A prison was a shul, because it was an ironic twist on the Yiddish term shul, meaning a religious school.

Vagrants might be caught by a schlamasse, or policeman, a word adapted from the Yiddish shlmazi, meaning unlucky. Avé-Lallemant also befriended a Roma woman, who helped him detect many Romani words in Rotwelsch, such as hachner for farmer.

In many ways, Avé-Lallemant did what generations of policemen had done before him: he decrypted what he thought of as a criminal language. But he also became the first to study its grammar, its uses, and the people who spoke it, with something approaching scientific rigor. He was a policeman who doubled as a linguist.

The study of Rotwelsch took a darker turn in the early 20th century, when it was swept up in a wave of anti-Semitism. A representative of this trend was a historian of names, Karl Puchner, who happened to be my grandfather. He denounced Rotwelsch and its speakers for being criminal and Jewish (neither was true: many speakers were not Jewish, and only some were criminal).

He made common cause with the Nazis and joined the storm troopers to keep the German language pure. He was policing Rotwelsch not simply to thwart criminal activity, as Avé-Lallemant had done, but to enact a racist ideology. (After the war, he managed to bury this past—until I chanced upon it while doing research at Harvard’s Widener Library.)

What I learned from this history of Rotwelsch, and my family’s entanglement with it, is that there does exist a strange connection between police and language—but it has little to do with our debates about words related to gender and race, with pressure groups seeking for change the way we talk.

Words can be arrested and studied by the language police, but they can’t be controlled for long.

Instead, the policing of language has to do with fears of foreigners and vagrants, with suspicions about languages of the underground and jargons of the disenfranchised, it points to the dark place where ideas about race and language get confused.

The history of Rotwelsch also shows that language tends to escape the clutches of police and scholars alike. Despite its best efforts, the (real) language police could never quite pin down this mobile language, which kept changing and adapting to new environments. I became aware of this dynamic towards the end of my research, when I was able to communicate with a surviving speaker, a member of a group in Switzerland.

He spoke movingly about the struggle to maintain an itinerant lifestyle in the margins of a modern state that suspects mobile people and mobile words. He had learned to distrust any outsider who showed an interest in the language and deliberately made up nonsense words to send nosy scholars and police on the wrong track.

My interaction with this speaker (who remained anonymous) was the redemptive end of a journey that had led me to the darkest places in European history. It reminded me that languages, especially those spoken at the margins of society, are surprising resilient, surviving many generations of persecution. Words can be arrested and studied by the language police, but they can’t be controlled for long. Like people, they want to be free.

__________________________________

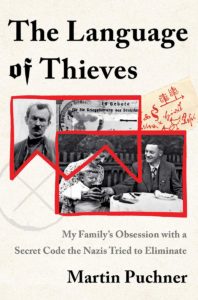

Martin Puchner’s book The Language of Thieves is available now.

Martin Puchner

Martin Puchner is the Byron and Anita Wien Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Harvard University. He is a prize-winning and bestselling author whose books include The Language of Thieves: My Family’s Obsession with a Secret Code the Nazis Tried to Eliminate and The Written World: The Power of Stories to Shape People, History, Civilization. He is the general editor of The Norton Anthology of World Literature. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Twitter @martin_puchner