London is a time-machine. As you walk through the city, you move through different eras: there is the house where Dickens lived, the hospital where Keats received his medical training, Shakespeare’s theater. You experience all the Londons that have existed, superimposed as in a palimpsest.

I was in London to research a particular time: the fin-de-siècle, that transitional period between the 19th and 20th centuries with the suspiciously French name. It was the time before everything changed, but change was already in the sooty London air. Women were adopting rational dress and agitating for the vote. Omnibuses were being replaced by electric trams, and London’s streets would soon be free of the horse-dung that had clogged them for centuries. The Kodak was starting to capture reality as it had never been captured before, to fix the moment on film. In Austria, Freud was discovering the unconscious, and in England itself, Hardy and Wilde were inventing what would become literary modernism. I wanted to write a novel set in that era—a novel about monsters. The fin-de-siècle was a great era of monsters: Mr. Hyde slinking through the Soho streets, Dracula stalking his prey in Piccadilly Circus. (Could he have used the first tube line? It was already built by the time he arrived in London.) Dr. Moreau, hounded from London by anti-vivisectionists, sailed to a distant island to create his Beast Men shortly before Wells’s Martians arrived to feed on humanity. This was the era in which mummies such as Stoker’s Queen Tera or Conan Doyle’s nameless Lot No. 249 came to life—no wonder, since it was also the age of archaeological digs in Egypt. Even Sherlock Holmes battled the Sussex Vampire.

It makes sense that monsters were prominent at the fin-de-siècle. The era inherited two important but countervailing 19th-century tendencies: the tendency to classify, and also to resist classification. The first of these tendencies was embodied in the Great Exhibition of 1851. In London, I saw traces of the Great Exhibition everywhere. In letters Prince Albert had written about the construction of the Crystal Palace, which housed its exhibits. In paintings of the exhibition halls filled with visitors, six million of whom came to see what was, despite its international character, a monument to British industrial superiority. Even in the geography of Hyde Park, where the Crystal Palace had stood. The Victoria and Albert Museum is filled with items that were displayed there. The Great Exhibition haunts London, like a ghost.

It was, at its metal and glass heart, one of the great classificatory enterprises, like Diderot’s and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie a century earlier. The Great Exhibition aimed to be both comprehensive and systematic: the exhibits were divided into four categories, each containing numerous subcategories, a classificatory system embodied in a three-volume Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue. We can think of this ambitious task, the systematization of all knowledge, as the great 19th-century enterprise. George Eliot mocked it in Middlemarch: Edward Casaubon’s attempt to create a Key to All Mythologies is a pedantic exercise that threatens to destroy her heroine, Dorothea Brooke. However, it was the basis for Herbert Spencer’s tomes on philosophy, sociology, and ethics, as well as Lyell’s Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man and Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. Walking through the Great Exhibition, visitors would see a world that was ordered, logical, comprehensive—and under British imperial rule. Darwin’s theory of evolution was particularly helpful to the classificatory enterprise: after the publication of On the Origin of Species, evolutionary status became the classificatory standard par excellence. The Italian criminologist Cesare Lombroso hypothesized that criminals could be identified by their physical characteristics because, like the troglodytic Mr. Hyde, they were evolutionarily closer to apes.

Around the same time, another sort of exhibition was becoming increasingly popular in London and throughout the English countryside: the freak show. Freak shows have existed since the medieval period, when congenital abnormalities were regarded as omens—signs from God that required interpretation. By the 19th century, they had lost that significance: monsters, whether two-headed calves or Joseph Merrick, the Elephant Man, had become objects of scientific curiosity, studied by researchers into teratology, the science of congenital abnormalities. They had also become popular entertainment. The transportation systems that brought a third of the British population to the Crystal Palace also allowed freak show performers to travel throughout the countryside. If the Crystal Palace represented order, logic, and imperial rule, the freak show represented what did not fit comfortably within categories—what was taxonomically problematic. Freak show performers broke through 19th-century categorical boundaries: like Jo-Jo the Dog-Faced Boy and the numerous bearded ladies of the circus sideshows, they were both human and animal, male and female—even, in the case of Chang and Eng, the Siamese Twins, both one and two. The freak show also had an imperial component, since some performers, rather than having congenital abnormalities, were simply from different cultures: crowds flocked to see the Aztec Children, the Small-Footed Chinese Lady and Family, and the Zulu Kafirs. The foreigner was also identified with the freak.

Although I saw traces of the Great Exhibition everywhere I went in London, to see the remnants of the freak shows, I had to go to the Royal College of Surgeons. There, on the second floor, you can still see a medical collection assembled in the 18th and 19th centuries that contains examples of congenital abnormalities: a two-headed chick, a four-tailed lizard. Such examples were used to demonstrate problems in development to medical students. However, the collection also contains the brain of the mathematician Charles Babbage, as well as the skeletons of the criminal Jonathan Wild and Charles Byrne, known as the Irish Giant, who worked on the freak show circuit. The genius, the criminal, and the freak were linked in the 19th-century imagination: they were outside the ordinary, the classifiable—and therefore monstrous. Taxonomic instability was part of the freak show’s appeal. Freaks such as Joseph Merrick and Julia Pastrana, who was advertised as the Bear Woman because her body was covered with hair, crossed taxonomic boundaries, including the boundary between human and animal that had already been problematized by Darwinian evolutionary theory. Monsters, whether mythological creatures or 19th-century freak show performers, have always been boundary-crossers and disruptors of categories. Freak show advertisements emphasized this volatility. One of the terms most frequently used for freaks was “nondescript,” a term implying that the freak could not be adequately defined or categorized.

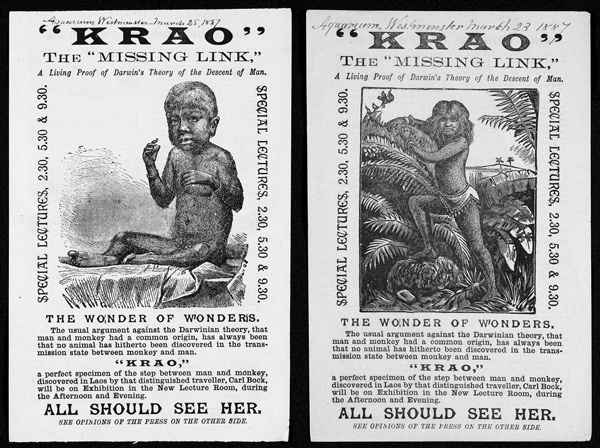

However, the impulse to categorize the monstrous is as old as the monster itself. Freak show advertising could also be used to contain the freak within a classificatory system. One of the most interesting and popular performers on the freak show circuit was Krao, the “Original Missing Link.” I came across her story while researching my novel, which takes place in London at the fin-de-siècle. The novel is about female monsters, including Mr. Hyde’s daughter and a Beast Woman created by Dr. Moreau. In her cultural context, Krao was a female monster: she was first exhibited in 1883, when she was only seven, at the Westminster Aquarium, a show space in London that featured theatrical performances, concerts, and freak show acts. She had been brought to London from what was then known as Siam. Like Julia Pastrana, she was one of the hairy women; her distinguishing characteristic was the fine, dark hair that covered her body. The showman G.A. Farini claimed that she was “Living Proof of Darwin’s Theory of the Descent of Man.”

By placing Krao within an evolutionary narrative, Farini could both categorize her and emphasize categorical instability. She was a modern atavism, an evolutionary throwback who demonstrated the validity of Darwinian evolution while reinforcing the evolutionary superiority of her English viewers. However, she also functioned as a source of frisson, reminding them of the scandalous Mr. Darwin and their own primate ancestry. Freak shows were so fascinating precisely because they provided a combination of discomfort and reassurance, calibrated to the audience’s cultural expectations. Krao was presented and advertised in different ways depending on what the audience expected to see. In England, she was often dressed as a middle-class girl, in a dress and boots, although her arms and legs were left exposed to show their hairiness. Contemporary newspapers noted her good manners and command of English, stating that since she had come to England and realized the benefits of civilization, she no longer wished to return to her own country. In France, she was more likely to be shown as an exotic and sexualized woman: more of her body was exposed and her primitivism was emphasized. The Darwinian narrative was less important than an image of savage life harking back to Rousseau. Krao spent her life on the freak show circuit, eventually marrying Farini and appearing with both Barnum and Bailey and the Ringling Brothers. To the end of her life, she claimed to be the “Original Missing Link,” presumably to distinguish herself from subsequent imitators.

There is one thing missing from Krao’s story: her voice. The monster is rarely allowed to speak. We are sometimes given glimpses of the monster’s point of view: from the perspective of Le Fanu’s vampire Carmilla, her desire to feed on Laura is an expression of love. But the narrative remains firmly in Laura’s voice. Before the 20th century, it is only in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein that the monster is given his own narrative—which causes us to wonder whether he is a monster at all, and whether his creator, Frankenstein, is the more monstrous of the two. Speechlessness is an aspect of the monstrous because monsters are expected to signify: they exist so we can read meaning into them. They exist for us, as Krao existed for her 19th-century audience. What did that little girl brought so far from home think and feel? What did she see when she looked into a mirror? Why did she marry Farini? Was she upset when other performers claimed to be the missing link? It marks a fundamental change in human culture that, after two world wars, as in John Gardner’s Grendel or the movie Shrek, we let the monster speak.

Since Julia Kristeva formulated her theory of abjection, it has been used as a theoretical framework to think about the monster: it implies that we produce the monster out of what is abjected, what we reject in the process of defining the human. Monsters are a way of policing our own boundaries. No wonder they became so popular during the fin-de-siècle, when those boundaries were being called into question. However, this framework does not account for the full complexity of how the monster signifies. As we see in Mr. Hyde, the Beast Men, and Krao, the monster is always hybrid: it is both human and inhuman, both other and us. That hybridity is what makes the monster fearsome and fascinating at once—we desire it (remember that Krao was presented as sexual in France, that Mina Harker does not want to resist Dracula) and recognize that it is never entirely out there, but also in here, like Ridley Scott’s aliens. When Edward Prendick returns to England after his stay on Dr. Moreau’s island, he sees Englishmen as Beast Men. We may use monsters to reinforce boundaries, but by their very nature, monsters threaten boundaries, showing us they can be crossed.

Each era creates the monsters that most signify—that mean in terms of its central practical and philosophical concerns. Frankenstein’s monster responds to Locke and the French Revolution. Dracula invades England during a time when the British Empire seemed strongest, but was already starting to crumble. Dr. Moreau’s Beast Men reflect, almost too obviously, contemporary concerns with theories of evolutionary change. What about the monsters of our fin-de-siècle, since we are living at our own turn of the century? They are not different in kind—we are inundated with vampires, mummies, and werewolves (literary versions of Jo-Jo the Dog-Faced Boy, a Russian named Fedor Jeftichew who was born with hypertrichosis and performed as a freak for Barnum and Bailey). But we treat them differently. Our vampires are both eternally attractive rock stars… and counting Muppets. We both identify with and tame the monster, while simultaneously creating a new narrative of the monstrous—serial killers and terrorists are our villains. They are not monsters, although we sometimes use that term for them: they are human, not hybrids. Perhaps they indicate that what we now fear, more than an other out there, is ourselves and our own capacity for evil. Two world wars have certainly taught us that. It makes sense, culturally, that Hellboy would join forces with the Americans to battle Nazis: in a battle against the worst of our own species, the monsters are on our side.

Our willingness to listen when the monster speaks indicates an openness to hybridity and ambiguity, to voices that tell us what we may not want to hear. At the beginning of the 21st century, we have problems that did not exist at the end of the 19th, when environmental degradation did not threaten global life. But our culture is also open to alternative discourses, to ways of being that used to be identified as monstrous when Wilde was compared in Punch to an animalistic Mr. Wild of Borneo. Although London is haunted by the Great Exhibition, it has become a monstrous city. As I walked down its streets, what I saw and heard was not just hybrid but polyvalent: a continual mixture of languages and cultures. If the Crystal Palace is indicative of its past, its future is presided over by Norman Foster’s skyscraper, a giant egg that looks as though it is about to crack open and release the sorts of aliens imagined by Wells and Scott. In that future, at once frightening and exhilarating, we will have to acknowledge that the boundary between self and other has always been something we create. How we perceive and present monsters will continue to change in response to our cultural needs—but monsters will always signify. They will always function as cultural barometers that allow us to gauge who we think we are, what we do or do not wish to become. Because monsters are always, finally, about us.

Author’s note: In this essay, I deliberately use the word “monster” to describe performers on the freak show circuit. The appropriate scholarly term for a professional freak show performer is “freak,” a word that acknowledges the extent to which performers were social outsiders, as well as the agency they often had in creating and directing their own careers. However, the late 19th-century medical term for a person born with congenital abnormalities was “monster.” I use the word to emphasize how freak show performers were perceived and their connection with contemporary literary monsters. If you would like to learn more about freak shows, and Krao specifically, please consult Nadja Durbach’s Spectacle of Deformity: Freak Shows and Modern British Culture, which first introduced me to Krao and her story.