Maud opened the window and the distant sounds of the valley filled the room. The sun was setting. It left in its wake massive clouds that clustered together and rushed blindly toward a chasm of light. The seventh floor, where they were living, seemed breathtakingly high. The view around them revealed a deep and resonant landscape that stretched right out to the somber streak of the hills of Sèvres. Between this distant horizon crammed with factories and suburbs and the apartment high in the open sky, the air, brimming with a fine mist, appeared thick and murky, like water.

Maud stayed by the window for a minute, her arms stretched out on the balcony railing and her head tilted to the side in the pose of an idle child. But her face was pale and etched with boredom. When she turned back toward the bedroom and closed the window, the humming of the valley suddenly stopped, as if she had closed the sluice gate of a river.

At the far end of the dining room stood the buffet. It was a very ordinary piece of furniture from the period of Henry II, but with time it had taken on the role of a silent character in the Grant-Taneran home. It had followed the family and they had eaten their meals off its chipped dishes for more than twenty years. Its style and the disorder that reigned in its shelves revealed a strange absence of taste. It was obvious to anyone who saw the buffet that the Grant-Tanerans never chose or bought furniture but made do with average-looking, more or less suitable pieces of furniture that had haphazardly been passed down to them through various inheritances.

Thus it was that they gathered around the Henry II– style buffet on the evenings they arrived home from their trips. And those evenings were always the most trying because they realized that they hadn’t yet left each other and that their old sideboard continued to observe them like the image of their despair.

Tonight on the buffet, the statement addressed to Jacques Grant from the Tavares Bank lay waiting for someone to open it. These statements regarding his debts often came at a bad time. This was an especially bad day because Jacques had just lost his wife, Muriel. She had died that very day following a car accident. Jacques was weeping in his bedroom, abandoned by his family, for it concerned Muriel, whom they knew very little, and each one possessed, besides their personal reasons for not reaching out to him, a reason common to all the Grant-Tanerans, a kind of contemptuous mistrust with regard to his expression of pain. So Maud didn’t go in to see Jacques, even with the excuse of the statement from the bank. Moreover, it seemed to her that the statement’s arrival wasn’t entirely bad timing; it bitterly highlighted the fateful character of this tragic and lethargic day.

In the dining room, things like her brother’s overcoat, scarf, and hat lay around in disorder, thrown over chairs. These finer objects always surprised Maud, because they were so different from her own things.

From the dining room doorway and down the dark, bare hallway came the sound of Jacques’s sobbing. Maud listened attentively, her tall frame leaning against the window and her face alert. She was attractive in this pose and her beauty emanated from her face like untamed shadows. Her pale, overly wide forehead made her gray eyes look even darker. Her face, with its skin stretched out over her prominent cheekbones, was attentively immobile.

Maud felt nothing except her heart, which was beating heavily. An irresistible disgust churned inside her, but her body held it in well, like the solid banks of a torrential stream. She listened to her brother’s sobs, this elder brother who at forty was twenty years her senior, weeping like a child. He had married Muriel barely a year ago, and this marriage constituted the most important event of his life, for he had never accomplished anything else. Since attaining his majority twenty years ago, he claimed jokingly that he had been content to put up with his family.

Mrs. Grant-Taneran readily accepted the idle and dangerous life her son led but, on the other hand, had never forgiven him for marrying a woman from the world he frequented. Although their quarrels were once quickly resolved, with Mrs. Taneran revealing her influence over him each time by calming down almost magically in the face of her son’s growing indignation, this was no longer the case.

Maud sensed their mother’s presence, alone, in the depths of the apartment, entrenched in the kitchen, her last place of refuge. There was no sound coming from the kitchen, but Maud knew the noise of the sobbing cut through Mrs. Taneran’s apparent silence. And considering the time this ordeal had lasted, since three o’clock in the afternoon (and it was already eight o’clock in the evening), the devastating effects of the sobbing must have been considerable.

The doorbell rang. The young woman went to open it. Her half brother, Henry, poked his head in with a childlike movement, barely showing his angular face and brown hair and looking like the spitting image of his father, Mr. Taneran. From Maud’s low voice and the uncustomary calm that reigned, he guessed what was happening. “So it’s over? Leave them alone and come with me. Let’s get out of here.” Maud refused. She turned on a small lamp beside her and waited.

In the dining room, things like her brother’s overcoat, scarf, and hat lay around in disorder, thrown over chairs.Shortly afterward, with the sound of a grating key, Mr. Taneran emerged from the shadows of the apartment hallway. He had a short mustache, a bit charred-looking, with despondent eyes set in a face carved with wrinkles as pronounced as scars. He was thin and rather stooped.

At one time Taneran had had a respectable career teaching natural sciences at the high school in Auch. Upon retirement, he had married Mrs. Grant, who was living in the city where her first husband had worked as a tax collector.

Taneran was just returning from the Ministry of Education, where, at over sixty years of age, he had been obliged to take up work again in order to meet the heavy demands that, since his marriage, had completely absorbed his personal fortune.

In reality, his family had easily adapted to his sacrifice. It should be added that since he had started working again, Taneran had managed to escape a little from the tyranny of his family and felt quite pleased about it. He had never become used to the inevitable constraints of family life and lived, moreover, in constant fear of his stepson, Jacques Grant. If he had not hesitated to marry Mrs. Grant even though she already had two children, it was because he had assumed that the older one would soon be getting along on his own.

He and Mrs. Taneran had had another son, Henry, for whom he felt a great deal of concealed tenderness, although Taneran quickly had to get used to the idea that his feelings were not at all reciprocated. Thus, to all appearances, Taneran lived a very solitary life.

On entering the apartment, he, too, understood that something unusual was going on and approached his stepdaughter in the hope that she would fill him in. “If you want, I’ll serve you dinner right away,” was all Maud felt like saying. At that moment, Mrs. Taneran called out in a weak, husky voice, “Maud, serve dinner to your father—it’s ready.”

The doorbell rang. The young woman went to open it.The young woman hurried to unroll a wax tablecloth, set a place, and enter the kitchen. Her mother had finally turned on the light and was reading the newspaper. Without raising her head, Mrs. Taneran repeated in a gloomy tone, “Everything’s ready. You can eat with your father, and if your brother Henry comes back, you can serve him, too.” Maud did not acknowledge that her brother certainly would not come home that night.

Dinner was quick. Taneran wanted nothing more than to retire to his room. Nevertheless, he asked Maud in a low voice, “She’s dead, isn’t she?” Maud nodded, and he added, “Fundamentally, you know, I don’t feel any ill will toward him. It’s very unfortunate.” He was masticating his food, and in the silence of the apartment it made a bizarre, irritating noise. Before going out he turned and said, “I don’t want to disturb your mother. Please say good night to her for me.”

His bedroom and the dining room shared an adjoining wall. Maud could hear him walking in his room for a long time. Under his feet the bare floor made a gentle creaking and cracking noise.

Maud felt at peace. For too long trouble had been brewing, that is, ever since Jacques and his wife had begun to be short of money.

As far back as she could remember, Jacques had been in financial difficulty, except for the first few months of his marriage. He was always in need of cash. This was by far the most important thing in his life. He existed in the center of a whirlwind, his head spinning over money.

Whenever he had any, he became another man. He possessed such an acute sense of his own inanity that he spent recklessly, throwing money out the window, deluding himself by using up funds in a few days that could have lasted a month. He smartened up his wardrobe, invited all his friends, and, with the magnificent disdain that his temporary opulence allowed him, didn’t appear at home for a whole week, avoiding this family who knew how to stretch out money so shamefully, so miserably, like others who hold back on using their full strength or enjoying pleasure, or like a dutiful servant who spares his masters any grief.

The young woman hurried to unroll a wax tablecloth, set a place, and enter the kitchen.When he no longer had anything left but a few bills and some change in his pant pockets, he bitterly measured his slim possibilities. He would set out on the hunt, trying to pawn off a friend’s old jalopy, and, not succeeding, would turn to gambling, going flat broke right away. Finally, worn-out and unapproachable, he would put himself into the hands of the members of the gang that had followed the same leads as he had for years and knew all the rackets. (Perhaps they were the only ones who felt any sympathy for him, although he detested them because they had seen him in the most shameful moments of his life.)

His wife’s money had disappeared as fast as the profits from his shady affairs. For several months, the couple had led what one would call a futile life, because it made no sense, but which, in reality, is very difficult to live: an idle and perfectly egotistical life, even though it appears generous, which consists of an uninterrupted series of moments of pleasure and respite, a continuous exorcism of boredom.

Muriel, who had entrusted her fortune to her husband, always remained ignorant of the ways in which he used it. She “detested expense accounts and never bothered with them.” Jacques was soon rushing around like a madman, trying to cover expenses he had allowed himself to incur.

Soon he began to beg. The little his family could give him had become appreciable of late. “I know you can’t give me much, but do what you can. A hundred-franc bill will be enough. I just need to hang on.”

“I thought your wife was rich,” countered his mother. “Don’t you think I have enough expenses already? ”

He didn’t answer so as not to spoil things, guessing that his difficulties were on the rise. And indeed, Mrs. Taneran had let go of less and less money, at the same time that her son’s needs continued to grow. This money, obtained through promises and pleas, represented more and more of the essentials for Muriel: stockings (“she has nothing left to wear”), the rent, or money needed to redeem a piece of jewelry, part of her “family heirlooms,” from the pawn shop. In the end, he stopped coming up with reasons to justify his demands. They had to eat. And again, he found appealing ways of making his requests. “She’s a wonderful cook, poor dear. If only you could taste her cooking. You’ll come, won’t you, Mother, when we have a bit more money? ”

“What about me? Don’t I know how to cook? You’re saying you didn’t like my cooking? Go on, say so . . . ” Mrs. Taneran detested him because love contains the dregs of hatred. In the end, she wasn’t unhappy with his romantic misfortune.

It didn’t take long for him to start playing highly emotional scenes. Stretched out as if he were sick, he would wait for someone to come and ask him what was wrong. “Nothing it’s nothing. But I won’t go back home tonight without a thing. She’s no doubt waiting for me, but I prefer not to see her again, to disappear.” The gang he had left a few months earlier had let him down. And so, acting on a supreme sense of family solidarity, his sister, brother, and stepfather all dug down to the bottom of their purses or pockets—all of themMaud, Henry, and even Taneran. They gave him, secretly, twenty, thirty, or fifty francs, with a feverish joy. He took pleasure, however, in vexing them. “Mother went along with it? ”

“No, she doesn’t want to hear any more about it.”

__________________________________

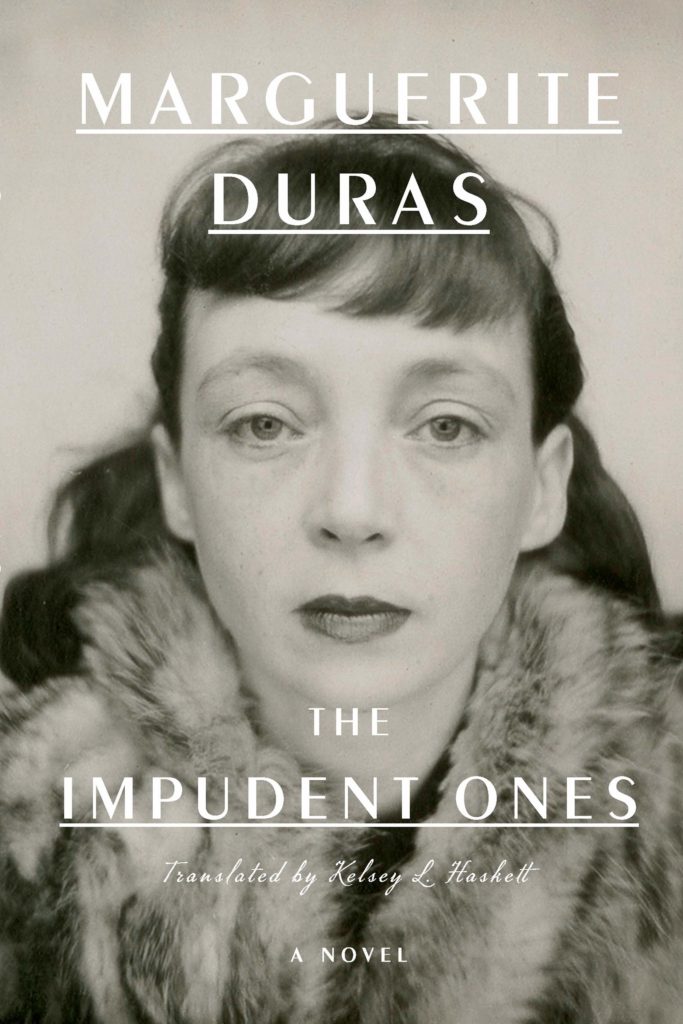

This excerpt originally appeared in The Impudent Ones, published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission. English translation © 2021 by The New Press.