The Immigrant Story is the American Story

15 Books By Immigrants That Changed America

As campaign season kicks off we’re going to be hearing even more about immigration than usual, though little of it is very enlightening. From Jeb Bush’s gaffes about “anchor babies” to reality-TV-star-turned-potential-leader-of-the-free-world Donald Trump’s insane claim that Mexico is sending murderers and rapists to the United States, our leaders are not exactly furthering the conversation. We can laugh (or cry) about the theater of it all, but it would be a mistake to dismiss what has been a perennial problem since Emma Lazarus wrote “The New Colossus”: Americans’ uneasiness about the “other” amongst “us.” Our leaders would do well to do some reading. From the days of the Founding Fathers—many of whom, of course, were first-generation immigrants themselves—those “others” have shaped the cultural fabric of our country and the meaning of America.

The Federalist Papers (1788), John Jay, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton

(Born in Charlestown, Nevis, Leeward Islands)

Founding father (and subject of the new rap-musical) Alexander Hamilton was born on the island of Nevis in the Leeward Islands and co-authored with John Jay and James Madison, under the joint pseudonym “Publius,” the series of essays that would come to be known as The Federalist Papers. These collected opinion pieces not only evangelized a skeptical American populace and ensured that we ratified the Constitution in the first place, but also affected more than any other document how we interpret our “supreme law” today.

The Birds of America (1827), John James Audubon

(Born Les Cayes, Saint-Domingue, later Haiti)

Nearly 200 years after it was first written and illustrated, John James Audubon’s Birds of America remains one of the most iconic works of naturalism ever compiled. The son of a French sugar plantation owner in Haiti, the six-year-old Audubon left for France and in 1803 immigrated to the US, where he began studying and painting birds. He gained enough confidence in his craft that in 1820 he declared that he intended to paint every bird in North America. In 2000, a copy sold for $8.8 million at a Christie’s auction, a record price for a book.

Anarchism and Other Essays (1910), Emma Goldman

(Born in Kovno, Russian Empire, now Lithuania)

Immigrants fueled the American industrial revolution—and often got caught in the gears of the machine of progress. At 16, Emma Goldman immigrated to Rochester, New York from Russia and got a job working long, underpaid hours as a seamstress. The news of the Haymarket Riot in Chicago a year later sparked in Goldman an interest in the growing anarchy movement, and she began to write fiery tracts in support of anarchy and women’s rights—two great fears of the establishment. Lauded and reviled, Goldman was known as the “the high priestess of anarchy” in her time, but now she is hailed as a civil rights warrior who was ahead of her time.

My First Summer in the Sierra (1911), John Muir

(Born in Dunbar, Scotland)

America’s best idea came into being in large part due to the efforts of a Scottish immigrant. Sierra Club-founder John Muir’s spiritual dispatches from Yosemite and the Sierra Nevada (and camping trips with the wealthy and powerful) brought eastward the magnificence of the ranges and sites threatened by westward-creeping industry, agriculture, and development, giving the preservationist movement the extra oomph it needed to bring about the founding of the National Parks.

The Prophet (1923), Khalil Gibran

(Born in Bsharri, Ottoman Syria)

Long before Richard Bach and Paulo Coelho turned spiritual humanism into a powerhouse literary genre, Lebanese immigrant Kahlil Gibran illuminated the literary world with his fascinating and strange book The Prophet, a collection of 28 poetic, epigrammatic essays that still inspires readers everywhere, with koans like these:

Only when you drink from the river of silence shall you indeed sing.

And when you have reached the mountain top, then you shall begin to climb.

And when the earth shall claim your limbs, then shall you truly dance.

Night (1955), Elie Wiesel

(Born in Sighet, Transylvania, now Romania)

Written by the Transylvania-born Wiesel, this seminal Holocaust book appeared in English at a time when doubt about the Shoah was first threatening to erase wartime memory among the American public. It has since had an impact on the country’s social consciousness equivalent to that of Frederick Douglass’s autobiography.

Atlas Shrugged (1957), Ayn Rand

(Born in Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire)

Russian-born Rand’s homage to the glories of capitalism has inspired legions of misunderstood teenagers, believers in American Exceptionalism (a coinage of a French visitor to the States, Alexis de Tocqueville) and the zealotry of The Tea Party, Alan Greenspan, and would-be namesake Rand Paul.

Lolita (1958), Vladimir Nabokov

(Born in Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire)

It took a Russian emigré to capture America’s sexual ambivalence, caught perennially between lasciviousness and prudery, and he did so with such potency that his book was instantly banned and still stirs up controversy half a century later. It was the peculiar genius of Nabokov to wrap this cultural atom bomb in what is perhaps the most formally accomplished novel of our time. As much about the seductiveness of language as about the language of seduction, Lolita puts on glorious display the linguistic virtuosity of someone for whom English was a secondary tongue.

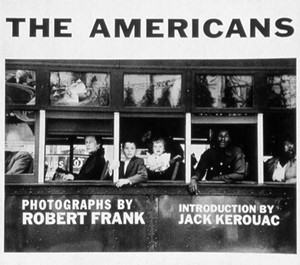

The Americans (1958), Robert Frank

(Born in Zurich, Switzerland)

Robert Frank, who was born in Zurich and immigrated to New York in 1947, changed the course of modern photography with this monumental portrait of American society in the 1950s. Frank spent two years traversing the country, snapping some 28,000 frames with his Leica, and giving us a whole new perspective on ourselves: jarring, unsentimental pictures of auto workers, cowboys, diners, cars, segregated cities, transvestites, and all the contradictory thrills of the American landscape.

Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963), Hannah Arendt

(Born in Linden, German Empire)

Arendt’s account of the trial of Adolf Eichmann gave us the indelible phrase and much-misunderstood notion of “the banality of evil.” A journalist-philosopher, Arendt suggests that the very worst deeds are not perpetrated by monsters but by ordinary people motivated by conformity and self-interest. Few books about the Holocaust and World War II still have the power to enrage and provoke like this one.

Black Power (1967), Kwame Ture, a.k.a. Stokely Carmichael

(Born in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago)

The future leader of the hugely influential Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee that helped drive the American Civil Rights movement in the 1960s emigrated from Trinidad to Harlem at the age of 11. His first year at Howard University, in 1961, Stokely Carmichael participated in the Freedom Rides to desegregate buses between Baltimore and DC. Later, Carmichael joined other Freedom Riders in Mississippi, where he went to work for the SNCC full time. In 1966 he uttered his most famous coinage: “Black Power,” which he defined as “a call for black people in this country to unite, to recognize their heritage, to build a sense of community.”

The Godfather (1969), Mario Puzo

(Born in Hell’s Kitchen, New York City to Italian parents)

It’s fitting that one of the most iconic American families ever rendered on the page, and later the screen, was a clan of immigrants. Mario Puzo grew up in Hell’s Kitchen during a time when the neighborhood earned its name, and when the Five Families who infamously ruled crime in New York City—and inspired the Corleones—were at their height of influence.

The Woman Warrior (1976), Maxine Hong Kingston

(Born in Stockton, California to Chinese parents)

Maxine Hong Kingston’s father emigrated from China to the United States in 1924, the year that the Asian Exclusion Act was passed—one of many such pieces of legislation meant to stem the tide of immigration from Asian nations. Growing up in the Chinatown neighborhood of Stockton, California, Kingston’s upbringing was conservative, in an environment where women were discouraged from pursuing careers outside the home. She turned her experiences into a landmark work of the Chinese-American experience, The Woman Warrior, a formal blend of memoir and Chinese folklore that Kingston would return to in her book China Men.

The House of the Spirits (1982), Isabel Allende

(Born in Lima, Peru)

The manuscript of The House of the Spirits, Peruvian-born Chilean-American writer Isabel Allende’s debut novel, began as a letter to her dying grandfather; we know it now as an essential and defining examination of life in 20th-century Chile. The book follows the fictional Trueba family over four generations and ends in a dramatic political upheaval, with a military coup that overthrows the socialist government—a plot point that closely mirrors the ousting of the author’s uncle, Chilean President Salvador Allende, by Augusto Pinochet.

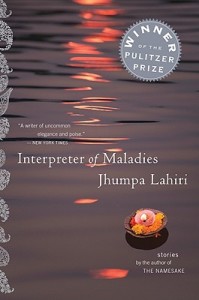

Interpreter of Maladies (1999), Jhumpa Lahiri

(Born in London to parents from West Bengal, India)

Winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 1999, the PEN/Hemingway Award in 2000, and named the Best Debut of the Year by The New Yorker, Jhumpa Lahiri’s first collection of short fiction has made a marked impact on American literature and culture. Though the stories in Interpreter of Maladies follow the lives of Indians and Indian-Americans in particular, they are, more largely, stories of displacement, and about understanding and redefining one’s cultural identity out of its context.

This list of great books by first-generation Americans is just a starting point. Restless Books is fostering the next generation with The Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing: $10,000 and publication awarded to an original work of fiction by a first-time, first-generation American author. We look forward to adding to this list.

Contributors: Nathan Rostron, Joshua Ellison, Jackson Saul, and Brinda Ayer.

Restless Books

Restless Books is an independent publisher of international literature, based in Brooklyn.