The Greatest Goths in Literary History

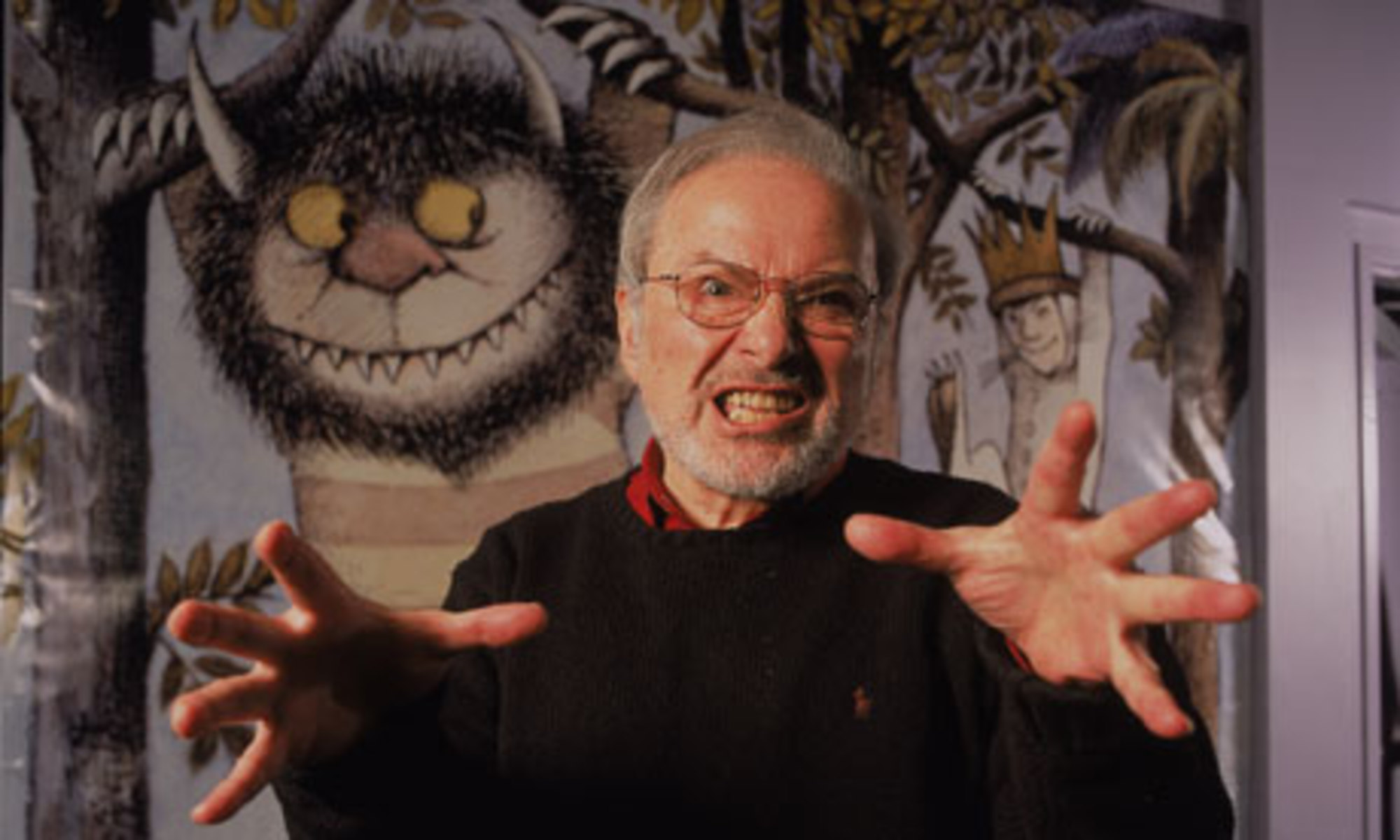

From Mary Shelley to Maurice Sendak

Today marks 220 years since the birth of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, whom you know as the author of Frankenstein and perhaps the greatest goth—literary or otherwise—that ever drew (hollow, ragged, romantic) breath. So, to celebrate her birthday (though honestly, she’d probably prefer a celebration for her death day), I was inspired to take a look at some other notorious goths from literary history, or at least those writers who have proved themselves goth-like. Since you asked, no, killing yourself doesn’t make you goth. Nor does writing gothic literature, unless you do it in a candle-lit cave or something. Goth is a style, a mood, an obsession with death, a wardrobe full of black clothing—well, it’s like art or pornography: you know it when you see it. See a few authors that I’d put in the category below—and add your own gothic favorites in the comments.

Mary Shelley was for sure the most goth author of all time—not only did she write Frankenstein, widely considered to be the first horror novel, but she also kept her husband’s heart wrapped up in a silk handkerchief on her person at all times. Here’s how it happened: Percy Bysshe Shelley drowned under mysterious circumstances a month before his 30th birthday. His remains, once retrieved, were cremated—but for some reason, his heart refused to burn. As if that’s not goth enough—apparently he may have suffered from a “progressively calcifying heart”—Shelley reportedly then carried his stone heart around with her for the rest of her life. After her death, the heart was found, wrapped in silk, in her desk drawer, along with a copy of Adonaïs, Percy’s elegy for Keats.

You may already know that Edith Wharton was really into her dogs. She was so into them that she buried them all in a doggy graveyard on a small hill visible from the window of her bedroom, which was also the place where she wrote some of her greatest works. She wrote until 11 each morning, gazing out at the ghosts of her dead dogs—whom, by the way, she also thought she could speak to.

First of all, Maurice Sendak famously said he wanted a “yummy death,” which seems pretty goth as these things go. More to the point, the creator of Where the Wild Things Are kept the original death mask of John Keats in a wooden box at the foot of his bed and would take it out and stroke it, and then lay it down on his own pillow after waking up in the morning. That wasn’t the only morbid piece of memorabilia he kept, either. According to Katie Roiphe, Sendak had a whole collection of “beloved objects that dealt with death: Mozart’s letter to his father telling him that his mother was dead. A Chagall funeral scene. A grief-struck letter he wrote at 16 to his future self on the day Franklin Delano Roosevelt died, full of lavish adolescent sorrow, railing against the people who just chattered and laughed as if nothing had happened. Wilhelm Grimm’s letter “Dear Mili, to a child whose mother had died.”

Sendak was obsessed with death from a young age, due in part to his many illnesses, and also because, as Roiphe explained, “when he was very small, his parents told him that when his mother was pregnant they went to the pharmacy and bought all kinds of toxic substances to induce a miscarriage, and his father tried pushing her off a ladder. . . He was unwanted, unwelcome, somehow meant to die, meant to be carried off.” Later in life he liked to sit with his loved ones as they were dying, and draw them.

Katherine Mansfield wore a black mourning dress and a black straw hat to her first wedding, which would be even goth-er if she actually liked her new husband, but she did not. According to biographer Jeffrey Meyers, though her “dress was grotesque and she was playing a tragi-comic role, [her new husband] did not seem to notice.” He noticed later, when she refused to sleep with him, and then left him in the morning.

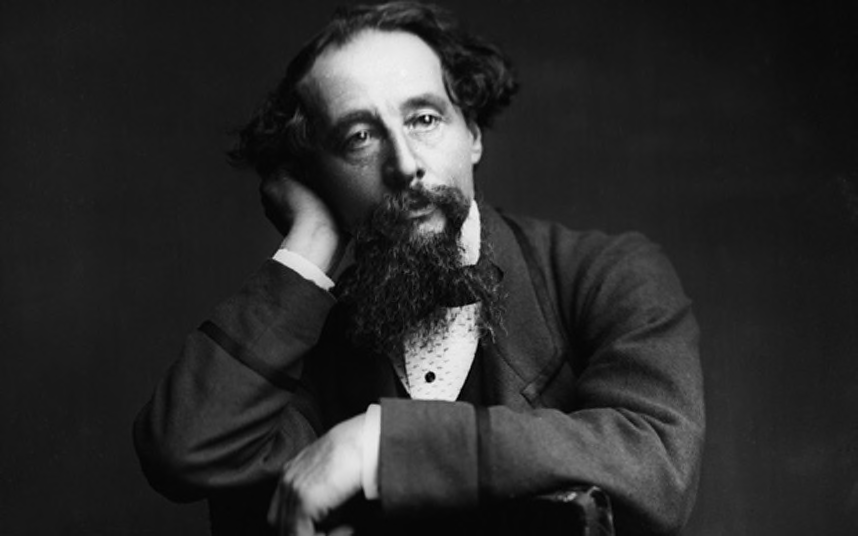

Everyone who’s anyone has a favorite spot in Paris. Clever wordsmith and #1 Victorian novelist Charles Dickens was no exception—his special place was the city morgue. In The Uncommercial Traveller, he wrote:

Whenever I am at Paris, I am dragged by invisible force into the Morgue. I never want to go there, but am always pulled there. One Christmas Day, when I would rather have been anywhere else, I was attracted in, to see an old grey man lying all alone on his cold bed, with a tap of water turned on over his grey hair, and running, drip, drip, drip, down his wretched face until it got to the corner of his mouth, where it took a turn, and made him look sly.

One New Year’s Morning (by the same token, the sun was shining outside, and there was a mountebank balancing a feather on his nose, within a yard of the gate), I was pulled in again to look at a flaxen-haired boy of eighteen, with a heart hanging on his breast—from his mother, was engraven on it—who had come into the net across the river, with a bullet wound in his fair forehead and his hands cut with a knife, but whence or how was a blank mystery.

To be fair, corpse-viewing was a bit more commonplace in Dickens’s time than it is now, but still—what’s more goth than spending your weekends gazing poetically at the dead?

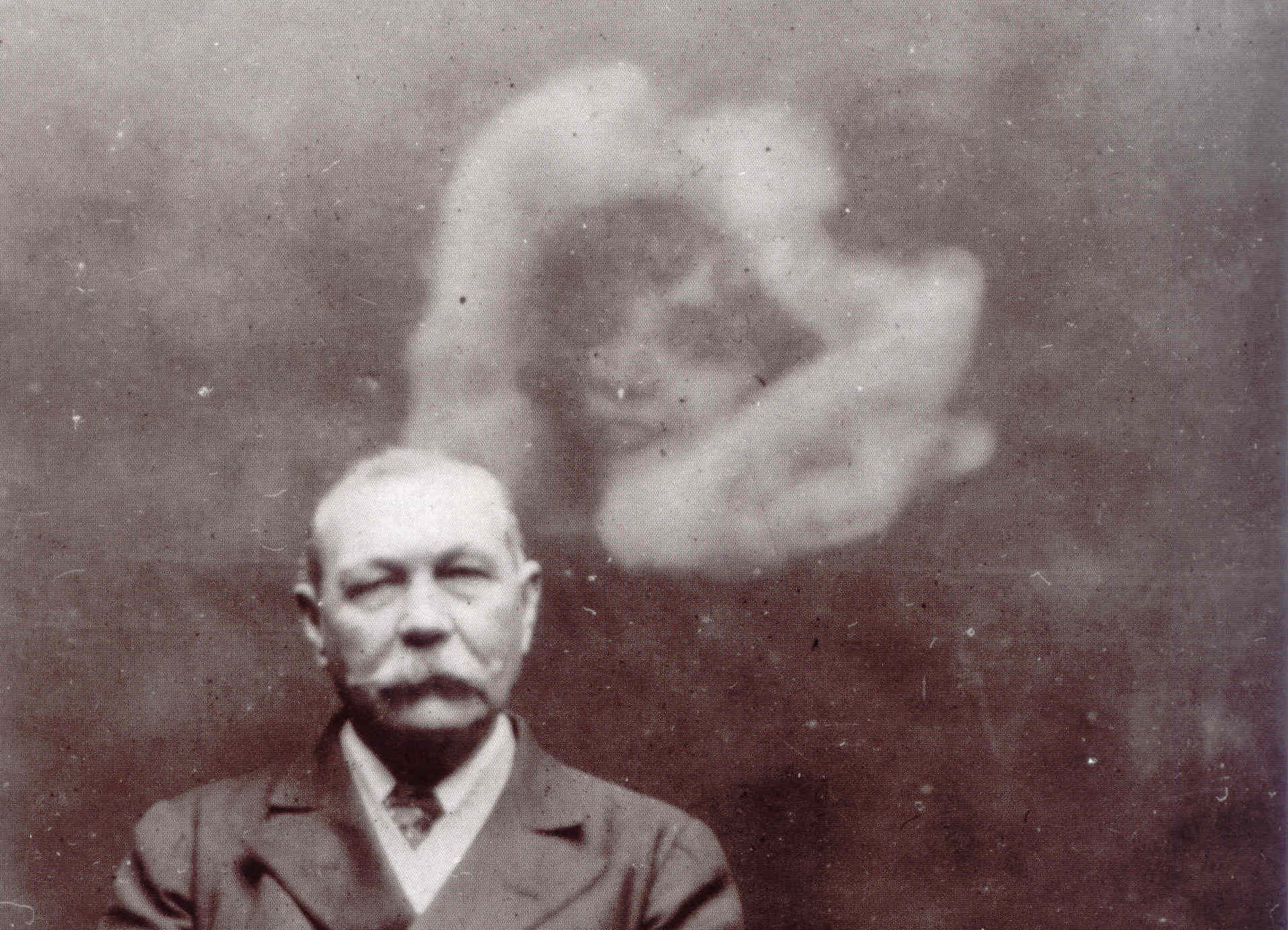

Best known as the creator of Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle was a fervent spiritualist, seance-attendee, spirit-photography-enthusiast, friend of Houdini, and member of The Ghost Club, the oldest group dedicated to paranormal investigations in the world. Basically, he believed that the dead were out there, and he wanted to talk to them. Apparently, his interest in the supernatural spiked when his son and brother both died of pneumonia within a four-month period, which seems only reasonable. This next part might not be very goth (or is it?), but it is worth mentioning: he also believed in fairies. Doyle was completely convinced by the so-called Cottingley Fairies—a series of photographs of fairies faked by two young girls in 1917—that he wrote a book, The Coming of the Fairies, declaring their veracity. He was later roundly mocked.

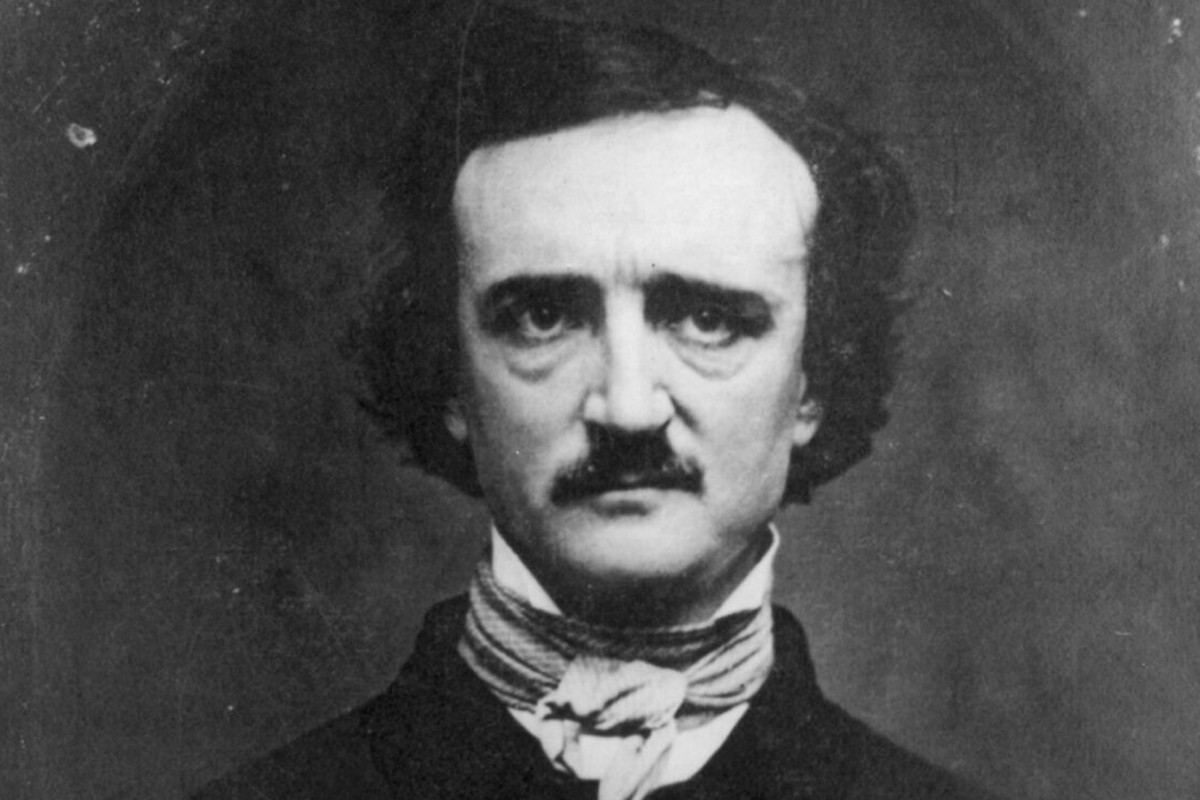

Edgar Allan Poe is actually not as much of a goth as pop culture would have it—until he began to devolve in his later years (due to drink and poverty, primarily), he was a relatively regular guy, handsome and athletic—but he’s the only author on this list (that I know of) that supposedly haunts his old favorite bar. There’s nothing more goth than being an actual ghost, right?

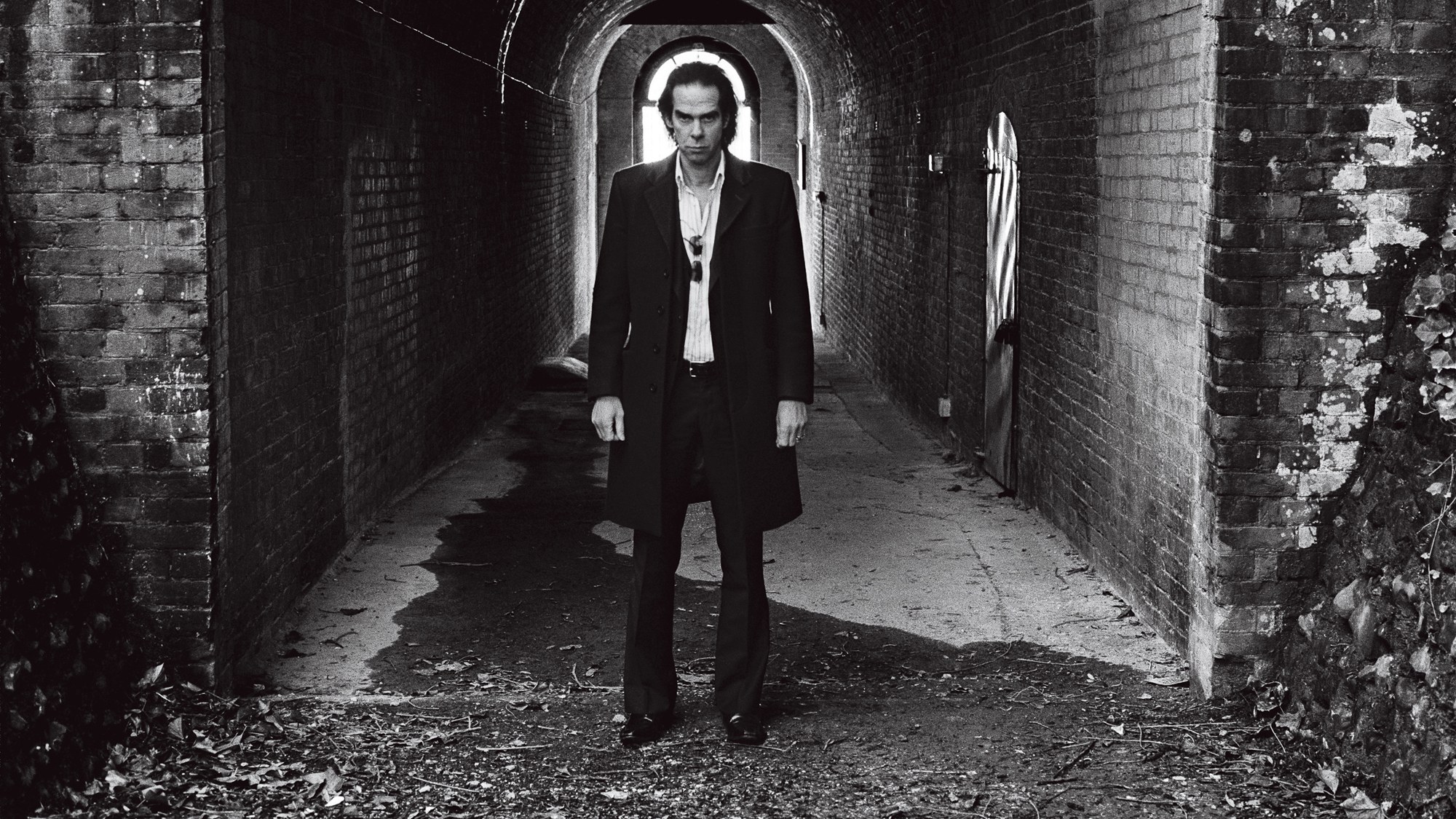

Well, Nick Cave is pretty much a gimme. But after all, he is a novelist, in addition to being the “grand lord of gothic lushness.” And honestly, just look at him.