The Governor’s Race That Made George Wallace a Hardline Segregationist

Peggy Wallace Kennedy on Her Father's 1958 Defeat

Political prognosticators agreed that the 1958 Alabama Democratic primary would not be won without a runoff. In 1958 and for four decades after, becoming the Democratic nominee was tantamount to winning the race. The November elections were only to make it official.

It’s strange that perhaps more than any other single factor it was Daddy’s opponent, John Patterson—a young, handsome lawyer from Phenix City, Alabama—who would shape our family’s future and impact national politics and race relations. None of us could possibly have foreseen that.

Patterson seemed congenial but he was a racist in his heart. He had been thrust into the consciousness of the Alabama psyche when his father, Albert Patterson, was assassinated by local gangsters following his attempts to shut down their illegal gambling operations. Following his father’s death, John took his place on the ballot and was elected. The loss of his father endeared John to the people of Alabama.

Although Daddy knew Albert Patterson, he was less familiar with his son, John. Patterson was not one of the movers and shakers, the Jefferson Davis Hotel lobby sitters who influenced Alabama politics. At first, Daddy was dismissive of Patterson: “All that kid has going for him is his dead father. That ain’t enough to get him to the governor’s office.”

Daddy had yet to come to terms with the notion that Patterson’s real appeal was his blatant racism. As the campaign began to tighten, and Patterson’s racial rhetoric began to attract the Ku Klux Klan and white supremacists, Daddy scoffed at the notion and shrugged off suggestions that he needed to solidify his support with the Klan—which was especially active in the late 1950s in south Alabama, where the state’s largest black population lived—by taking a position to the right of Patterson on the issue of integration.

Daddy continued to think that his best chance was to rail against income inequality and large corporations while promoting public education and promising roads, roads, and more roads. He targeted the concerns of the common man and headed to vote-rich north Alabama during the final weeks of the primary election, leaving Patterson to gin up the racists in the south.

Mama’s friends dropped by, sipped coffee at the kitchen table, and gave Mama fashion tips on what they thought a First Lady should wear.Patterson and Daddy headed toward election day neck and neck. Daddy’s pace was frenetic. His campaign workers and volunteers were pushed to the limit, and Mama joined him at rallies in North Alabama. He was on the verge of collapse: his voice was always hoarse and his suits hung slack on his gaunt frame. The only race he ever lost was as a college freshman when he bucked up against the college fraternities and ran for president of the Cotillion Club.

On June 3rd, Daddy came in second place: 162,435 votes, or 26 percent, to John Patterson’s 196,859 votes, or 31 percent; the rest of the votes went to third-tier candidates. Daddy had three weeks to turn it around.

During the runoff, Patterson campaigned fiercely throughout the southern part of the state and continued to rely on racial rhetoric and his promises to keep Alabama white. He “was honored,” he said, to be running with KKK support. He reminded white voters that as Alabama’s attorney general, he obtained a restraining order to bar the NAACP from operating in Alabama on the grounds that it was not registered as an Alabama corporation.

He made much of his suit against the Tuskegee Alabama Civic Association, a negro group that instigated an economic boycott in Tuskegee in protest of white attempts to gerrymander the town to protect white control. He did everything he could to remind the KKK and white voters that he was on their side.

*

On the morning of the runoff, my parents mingled with supporters on the courthouse steps in Clayton before going inside to vote. Daddy dropped Mama off at the house before heading to Montgomery. Mama fussed with her clothes as she packed her bags to travel to meet him. There was excitement in the house: a “we just know he is going to win” attitude prevailed.

Mama’s friends dropped by, sipped coffee at the kitchen table, and gave Mama fashion tips on what they thought a First Lady should wear. There were giddy discussions about what it would be like to live in such a grand place as the Alabama Governor’s Mansion with cooks and handsome men in uniforms to drive Mama around.

When we arrived in Montgomery, the mood was festive. The air in the Greystone Hotel’s ornate lobby was thick with cigar and cigarette smoke. Mama took us to our rooms. Daddy was with a small group of his campaign advisers, phoning county courthouses and campaign workers across the state.

“Peggy Sue, where are you?” Mamaw’s sister, my Aunt Bill, yelled out in her singsong way when she walked in our room. “I brought something special, just for you.” She handed me a brown paper sack that was folded at the top. She looked over her shoulder at Mamaw. “I know I should’ve wrapped it, but I just slam ran out of time.” I reached into the bag and pulled out a pair of pink plastic play high-heeled shoes. “Sugar,” Aunt Bill said, “put those Cinderella shoes on and let’s go downstairs and priss outside while your mama gets dressed.”

I felt glamorous, although unsteady on my feet, as Aunt Bill and I walked along the downtown sidewalk. Aunt Bill pointed to one of the stores. “This is where your mama will take you shopping when your daddy wins.”

My grandmother Mozelle’s stoicism, her commitment to “never let anyone see you cry,” had been passed down to my father.We returned to the hotel and were waiting in a crowded suite when the first hint bloomed that Daddy could lose the election. As evening turned to night there was still hope that voting boxes in north Alabama would heavily favor Daddy and offset the lopsided numbers for Patterson coming from the state’s southern counties. But as the night wore on, it became apparent that John Patterson would become the next governor. His hard-line racism had given him the edge. My father had lost.

*

Daddy gathered us up and took us to a waiting car to drive to a local television station on the outskirts of Montgomery. He was going to concede. I sat in the middle of the front seat next to Daddy and buried my face in his side. I felt his arm surround me as he pulled me close and whispered: “Well, we lost, sugah, but it is goin’ to be all right. Sweetie, now don’t you cry.” The tears I was drying with the handkerchief he pulled from his pocket were not for me, they were for him.

While he was making his concession speech, we sat in the lobby to wait. Directly across from me there was a large wire cage, barren and rusting. Inside was a small monkey. I can still see it 60 years later. It looked as sad and lost and forlorn as I felt.

Following Daddy’s televised remarks, we were driven back to the Greystone Hotel. A crowd of supporters, some crying, greeted him on the sidewalk as he stepped from the car. It was time for him to speak to his campaign supporters who were waiting for him. He was gracious in defeat. This is just the first round, he must have thought—I can hold on for four more years. He contained his anger and disappointment. My grandmother Mozelle’s stoicism, her commitment to “never let anyone see you cry,” had been passed down to my father.

Although there is disagreement about the events that immediately followed, depending on who tells the story, and overlooking Daddy’s vague memory on the subject, it is generally agreed that Daddy said at some point that night, “I’ll never be out-ni**ered again.”

Those five words, spoken in the heat of his intemperance and rage, would follow us for the rest of our lives.

Later on in his life, Daddy told me several times that he had never said that. “Seymore Trammell, or somebody in his camp, just made that up. I would have never used the N-word like that.”

Perhaps Daddy did not say those words on that night in 1958. But during his first term as governor, Daddy stood in the schoolhouse door, never punished or fired the state troopers that attacked marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and sent law enforcement officers to Birmingham to support Bull Connor’s reign of terror in the summer of 1963.

__________________________________

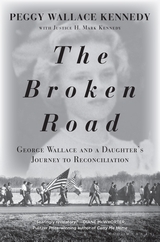

From The Broken Road: George Wallace and a Daughter’s Journey to Reconciliation. Used with the permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury. Copyright © 2019 by Peggy Wallace Kennedy.