The French Satirist Who Brought Anarchy Into Art

On Georges Blondeaux, or Gébé

There is an Henri Cartier-Bresson photo of a fivesome from above and behind—all of them rather bon vivant, not to say portly—on the sloping banks of the Marne. Around them in the grass, on newspapers and a rumpled blanket, lie the ruins of a picnic, even as one fellow in a Borsalino and suspenders pours himself another glass of red. Leisure comes off the image in waves, like warm summer air.

In the late 1930s, when he took the picture, Cartier-Bresson was coming off Surrealism’s influence into a decade of political engagement that would see him working for the communist press. Between 1936 and 1938, he produced a series of photos that caught citizens of the Parisian region celebrating the simple joys afforded by the first paid vacations: one of the great political victories of the Entre-deux-guerres, that short-lived interwar period during which modern France’s mythical reputation for the good life was largely forged, much of it thanks to the even shorter-lived Front Populaire (a coalition of the Communist, Radical, and Socialist parties with the Workers’ International), which with the Matignon Agreements in 1936 secured such complementary legal fundamentals as the right to strike, the right to unionize, and the 40-hour work week.

Simple joys, our common human right to them, and the playful, even surreal shifts of perception that might bring them closer, would become presiding themes in the work of Georges Blondeaux. In 1936, he was seven, the only child of working-class parents in a suburb of Paris. Just over decade later, he joined the SNCF, France’s national rail service, as a draftsman and design technician, and a decade after that, the first single-panel editorial cartoons signed jaggedly but inimitably “Gébé” (the French pronunciation of Blondeaux’s initials, “G.B.”) began to appear: first in the SNCF’s house organ, La vie du rail (Life on the Rails), back from its wartime hiatus, and then in periodicals from the mainstream (Paris-Match, Le Journal du dimanche) to the fringe (Radar, Bizarre).

But it was not until 1960 that Gébé went “off” the rails, quitting his industrial job and fully embracing his calling as an industrious anarchist. In the years to come, he was to exercise his gift for whimsy and satire, absurd yet urgently humane, in everything from cartoons to prose fiction, radio plays to photo-novels, movies to song lyrics. He claimed to love 19th-century Russian literature, American science fiction, and Scandinavian theater. He penned a hit song for Yves Montand that manages to link political assassinations, Czech phenomenologist Jan Patočka, and clubbing baby seals. “The true anarchist,” wrote Pacôme Thiellement in a posthumous appreciation, “does not make: comics, literature, paintings, music, or cinema. The true anarchist makes anarchy in comics, literature, paintings, music, or cinema.”

In 1953, Guy Debord had spray-painted his famous “Never work” on the banks of the Seine. To hear Gébé himself tell it, he woke up one fine spring morning toward the end of the same decade and said, “No! Today I stop selling, at a three-hour round trip from here, eight hours of my life on a daily basis.” By the next year, he had joined the crack squad whose creation would change the face not just of satire but journalistic freedom in France: the infamous Hara-Kiri. In its motto, taken from an outraged reader’s letter, the magazine inspired by Harvey Kurtzman’s MAD proudly branded itself “stupid and mean.” Its early roster was a Who’s Who of scathing French humor: founders François Cavanna and Georges Bernier (a.k.a. “Professeur Choron”), Fred, Reiser, Roland Topor, Cabu, Willem, Wolinski, Lob, Delfeil de Ton.

To Hara-Kiri, Gébé contributed cartoons, prose faux-reportages, and sketches for photos later staged with live models as color covers. “What that fellow was able to convey in his spare, deadpan lines!” the excitable Cavanna crowed in his memoirs. “His brain hummed away by itself in its own little corner like a superannuated yet highly subtle machine whose gears had been lovingly oiled.” The more mordant Choron claims that the draftsman’s exactitude could always be detected in his style.

But for Gébé, such tight-winding was the springboard to greater heights of lunacy—locating, like Bergson, comedy in the machine gone haywire. Rigor of art and argument lent his humor its off-kilter power, the sense of madness bristling in the schematics. When the Hara-Kiri weekly was shut down a scant decade later for mocking the death of General de Gaulle, its successor Charlie Hebdo sprang up almost immediately, while the Hara-Kiri monthly marched on with Gébé as editor-in-chief.

Hara-Kiri, if not central to the May ’68 protests, had a definite hand in goosing a prudish France into a more permissive media era. Gébé and several Charlie comrades began branching out, publishing in the long-running comics revue Pilote (home of Astérix and Valérian), as well as the short-lived, incendiary rag L’Enragé. But, riding the high of post-’68 enthusiasm, Gébé was preparing his own call for change, markedly more fanciful than his fellows’. Could his categorical “No!” be extended to all humanity? “Stop everything. Think. It’s a good thing!” became the cheery motto of his daffy utopian comic strip L’AN 01 (Year 01), which frst appeared in October 1970 in the pages of Politique Hebdo. “There was,” he wrote in a later afterword on its origins, “the idea, bracing as salt air, of vacationers who, having spent their sojourn reflecting, were firmly resolved not to go back to things as they were. And the jubilation I felt welling up, steadily overflowing into everything.”

What is it with French revolutions and rebooting the calendar? With L’AN 01, Gébé went from being the cog that quit the machine to impishly tossing grit in the gears, a wrench in the works. What he proposed was both modest and radical, literal and metaphorical: “a step to the side.” What would happen if we all took a step sideways? Lines would no longer match up with windows, rifles would fall down for lack of recruits, laborers would no longer be at their places on assembly lines, and at the bar, “you’d have to sip from your neighbor’s cup: no harm done!” Such implacable extrapolations of consequence along the lines of whimsy were a signature move, practiced derailments (déraillement) akin to Situationist subversions (détournement).

If, as a thought experiment in utopia, L’AN 01 seems overstuffed, well, “you need a lot utopia of to start with,” Gébé advised, “because it cooks down.” The book brims with suggestions too outlandish to be taken literally (except when acted out by readers) backed by intentions too serious to be taken as anything but (except when meant in jest). Its population lives on noodles, and its department stores have become museums, but its stakes are the life and death of society and the soul. In his repudiation of violence, his refusal to choose between “the weapons of production” and “the weapons of revolt,” his faith in sovereign imagination (“Imagination calls us only to imagine”), and his pursuit of joy as the only true awakening, Gébé recalls Raoul Vaneigem, the hero of whose 1967 classic The Revolution of Everyday Life (the poetry to Guy Debord’s theory) was “the man of survival . . . ground up in the machinery of hierarchical power. . . the man of absolute refusal.”

Rigor of art and argument lent Gébé’s humor its off-kilter power, the sense of madness bristling in the schematics.

Over the course of the next three years, L’AN 01 would become a transmedia event avant la lettre, a collective film in which Gébé invited people across France to freely participate, supplying prompts for scenes in his comics pages for Charlie Hebdo. The eventual result—a real movie, including sequences directed by Jacques Doillon and Alain Resnais, and featuring over 300 actors, from Coluche and Miou-Miou to the Hara-Kiri staff and the first film appearance of Gérard Depardieu—was a minor hit. The L’AN 01 strips were collected in book form by Hara-Kiri’s parent Les Éditions du Square, which also published Gébé’s cartoons and photo-novels.

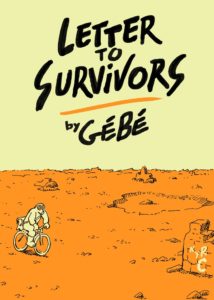

We all know what happened next. The oil crisis. The Cold War came back. The 1970s became the ’80s, even in France. In 1981, the government shuttered its Ministry of the Quality of Life, founded less than a decade earlier. Les Éditions du Square folded, taking Charlie Hebdo and Hara-Kiri with it. The intermittent Zéro, a magazine from the pre-Hara-Kiri days of Cavanna and Choron, was resurrected with Gébé as editor-in-chief, lasting a mere year. Gébé turned to writing prose novels. But before that, he gave us one slim, disillusioned volume composed from a pained rage at the imminence of global immolation, the dystopian Letter to Survivors. True humor is never far from suicidal.

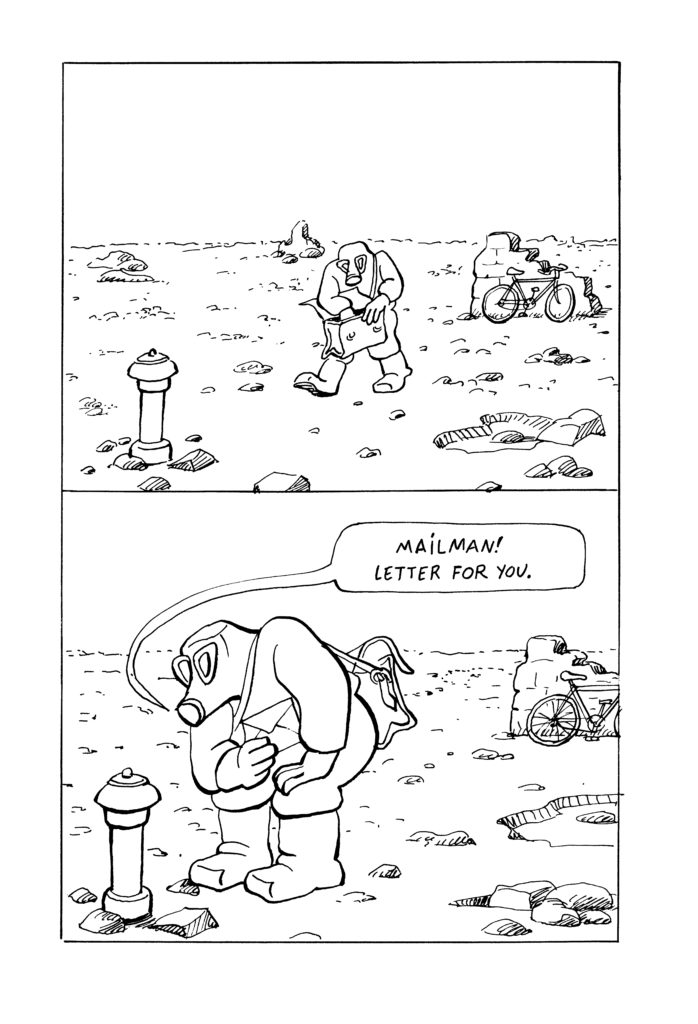

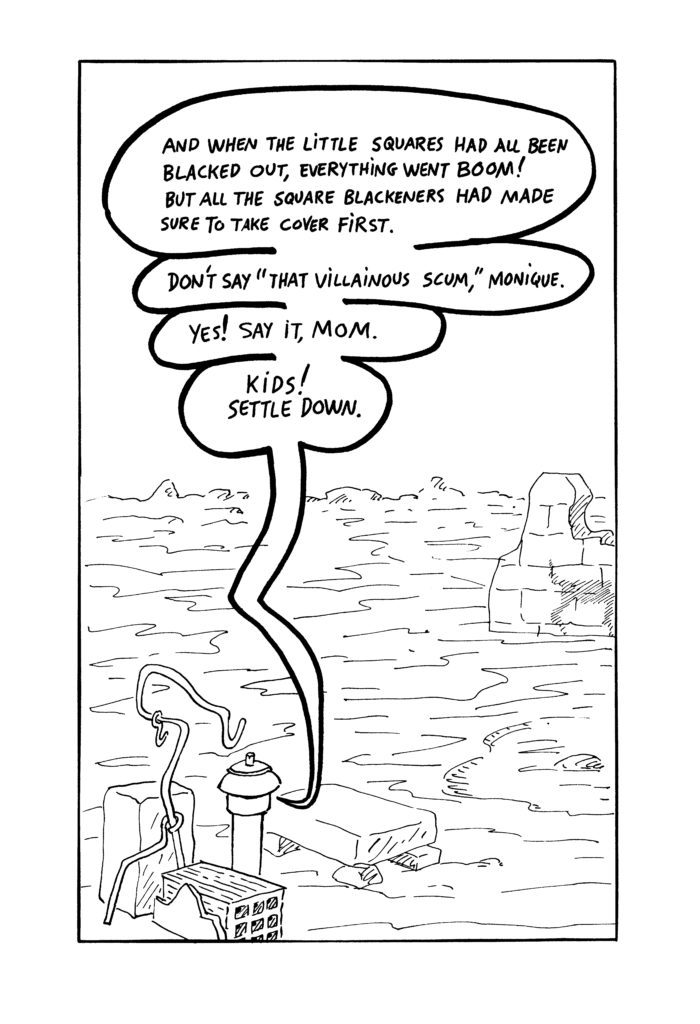

American science fiction is hard science, European science fiction is hard humanities; so goes the stereotype. And in keeping, Letter is short on how-to, long on how-did-it-ever-come-to-this? If L’AN 01 was a Whole Earth grab bag of poetic tactics to awaken the imagination, in Letter to Survivors it was as if a disillusioned Stewart Brand had put out a special follow-up issue wholly devoted to fallout shelter living. Instead of gung-ho can-do and helpful tips, Letter serves up mockeries of advertisement and fragments of familiar genres. Gébé gives us a series of vignettes nested in a post-apocalyptic postman’s narration.

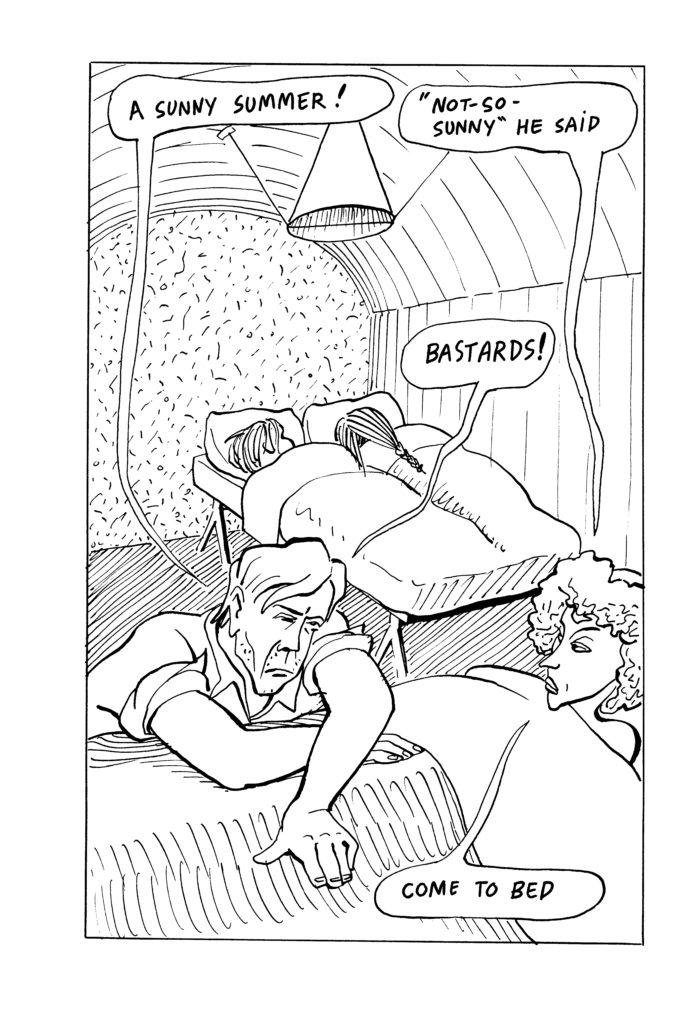

In his short fiction, Gébé was fond of parodying popular genres, from mystery to pastoral to fairy tale. Here, we find a torpid story of love and detection by the seaside, a bucolic idyll of Sunday walks and country cafés, a magic lantern show: time-honored settings likely to stir in readers memories of family outings and childhood holidays. Each strays further back in time, seeming to follow the specious narrative of nostalgia, wherein the good old days are made to glow gold through the alchemy of longing. While L’AN 01 exhorted us to leave our jobs for the natural state of leisure, in Letter such opportunities are severely curtailed; these evocations are but reminders of loss. The past is a trap, and the present a wasteland.

The postman’s inscrutable goggle eyes and filter snout visually echo Gébé’s early breakout character, the inhuman prankster Berck (a homophone of beurk, the French for ick or blech), a dwarfish, potbellied, errant, and imperturbable id of simple desires who eats fresh fish and flowers. Both Berck and the postman are equal-opportunity offenders (though the postman is unionized) with a bit of Renoir’s Boudu about them, reminding us through wile and casual havoc of our best instincts, bringing a new meaning to the words “masked hero.” The postman’s mission is to introduce a grain of sand into the oyster of the bunker, grit enough to agitate. Through him, Gébé means to awaken us to indignation, to the intolerability of our circumstances, the extent of our passive and successive amputations. Though the worst has not yet happened, so many of us live as if it were at once impossible and inevitable, in a state of willful ignorance and spiritual resignation.

Witness the mother’s alcoholic disintegration, hitting rock bottom in a bomb shelter. A few deft lines are enough to render her bitterness, and yet her pinched face recalls more than any other family member’s the abstract visage (geometrical and hardly idealized) that is arrested by the dual smells near the gazebo in the fondly remembered town square. By the defeat of our hopes and dreams, we have been driven underground already, but Gébé wants to get us back to a place where, out of rage, we might begin to dream again. “We’ll be waiting for them right outside their five-star bomb shelters,” the trapped mother of Gébé’s nuclear family vows. “They’ll expect to get butchered but all we’ll do is spit at their feet.”

By 1992, Philippe Val had resurrected Charlie Hebdo, and Gébé was brought on as managing editor. The revolution, back in fashion, spent the decade resting on its laurels and canonizing its survivors. Shortly before his death in 2004, the pivotal indie comics publisher L’Association began reprinting Gébé’s greatest hits, and a decade later came a retrospective exhibit. But the genial anarchist and cartoonist’s cartoonist, who by temperament shunned the limelight, remained a name for those in the know, never quite achieving the renown of his more overtly political comrades like Wolinski or Cabu—often to the surprise of the same. At the news that critic Jean-Charles Vidal had proclaimed him a genius, Gébé is said to have exclaimed, “Merde! Don’t let it get around, or they’ll can me!”

Over 35 years after its initial publication, this letter from one era of staring down the missile silo has reached another, none the wiser. Armageddon, nuclear and non-, is timely again and its aftermath more popular than ever, if also smacking faintly of nostalgia, an almost nihilistic longing for the prophesied doomsday that never came to pass. It is hard to tell real panic from the retro-post-apocalyptic. It has been almost midnight for such a long time.

__________________________________

From the introduction to Letters to Survivors. Translation and introduction copyright © 2018 by Edward Gauvin; Images copyright @ Gébé and L’Association. Rights arranged through Nicolas Grivel Agency.

Edward Gauvin

Edward Gauvin has translated more than 300 graphic novels, including Blutch’s Peplum (NYR Comics). His work has won the John Dryden Translation prize and the Science Fiction & Fantasy Translation Award and has been nominated for the French-American Foundation and Oxford Weidenfeld translation prizes. He is a contributing editor for comics at Words Without Borders and has written on the Francophone fantastic at Weird Fiction Review. Other publications have appeared in The New York Times, Harper’s, Tin House, World Literature Today, and Subtropics.