“Smoke and Burnt Pine”

Nat Turner saw hieroglyphic characters on the leaves. Written in blood, they portrayed men in different poses, the same he had seen in the sky when the Holy Ghost had said to him, “Behold me as I stand in the heavens.” The spirit revealed itself in a stretch of lights spanning east to west—the Savior’s hands extended on the cross. Now amid signs closer by—the dew on the corn, the blood-men on the leaves—he understood that Jesus had risen to heaven and come back to earth. “As the leaves on the trees bore the impression of the figures I had seen in the heavens, it was plain to me that the Saviour was about to lay down the yoke he had borne for the sins of men, and the great day of judgment was at hand.”

Turner owned a Bible, a pocket-size volume about five by three and a half inches, densely printed on thin paper. Tattered and rounded at the corners, its front and back covers torn off along with its opening and closing chapters— Genesis, Exodus, Revelation—it is now a contact item, a holy relic: not only Turner’s personal book but the one he is said to have held when captured on October 30, 1831, some two months after he led the rebellion on August 21 of that year. As Turner saw the signs, now this Bible is the sign of him.

History in that Bible is dense and thin, portable and hidden, an illegal literacy of self-begotten truths. It speaks the words of heaven but it was also down in the hole where Turner hid, in a pit he dug with his sword beneath the crown of a fallen tree, its toppled peak lying in a clump of fence rails. The truth resided in unlikely places, concealed in plain sight, not far from the events it ordained, where sky and earth rose and resided. After the rebellion, Turner was as before: “wrapped . . . in mystery.” No martyr but the man, no deed or doctrine but by his own hands, cupped in palms of the Lord unseen.

He had cogitated his plans at a self-secluded place in the woods. William Styron imagined it as “a mossy knoll encircled by soughing pine trees and cathedral oaks.” In that place not far from the home of his master, Joseph Travis, Turner “built a shelter out of pine boughs,” using it as his “secret tabernacle,” where he would stay for days at a time, fasting to hear better the voices of prophets. “The crashing of deer far off in the woods became an apocalyptic booming in my ears,” reflects Styron’s Turner. “The bubbling stream was the River Jordan, and the leaves of the trees seemed to tremble upon some whispering, secret, many-tongued revelation.”

The strokes of the axe that killed the master Travis and his wife on the night of August 21, 1831, made another order of time. They split the moments not just into before and after but into ever-finer divisions and subdivisions, a whole real estate of life and death, bordered suddenly, it seemed, by nothing finite at all. Towns and counties took flight; maps lost their legends. The Travis bedroom became a laboratory in which moments, shaved by an axe, revealed an eternal hue, a rainbow glossolalia, spoken in tongues of smoke and burnt pine, a drought and parchment of terrific thirst. In that loss of speech, clouds severed from the sky and stains fell like rain, revealing no dream but of the end of time, no way of effecting that dream but in the time the dream annulled, and no wonder but the blade, in a shiver infinitesimally fine. All that remained were ordinations of territory unclaimed: no rule but abandon, no order but the one unbound, a country of the spotted leaves.

“Sculpting Thomas Jefferson’s Face”

Down the paths of Monticello the New York sculptor rode. John Henri Isaac Browere was arriving to make a plaster life mask of Thomas Jefferson, then eighty-two years old, using his secret process. The elderly Jefferson had recently broken his arm falling into a stream when his horse stumbled on the muddy bank, and he was in declining health generally. The business of slathering his features with plaster to achieve a remarkable “face”—indeed so lifelike as to seem less like a sculpture than a type of protophotograph—seemed too arduous for him to endure. But James Madison had provided Browere a letter of reference, Jefferson’s family wanted the mask made, and the former president felt he could hardly deny a person who had come so far.

There was a reason to consent. A Browere sculpture made the man, preserving him for all time. It made him so exactly that there seemed no art at all, just a pure transcription of his features. It was “so simple and direct that, next to the living man, he has preserved for us the best we can have—a perfect facsimile.” Other mold makers could not rid their masks of the somnolence of the sitter—the subject needed to be nearly comatose, a mass of slackened features, beneath the plaster—but Browere and Browere alone had figured out how to keep those features animate, perky. This was his miracle, his secret. But at Monticello it did not go well. Jefferson lay on his back on a sofa, grasping a chair with his good hand. His family did not want to see him with the plaster coating his face, so they left the room, leaving him and the sculptor alone with Jefferson’s trusted slave Burwell, who stayed to look after his master. After Browere laid on the plaster, Jefferson began having trouble breathing. He tipped the chair he held in one hand up and down, knocking the legs on the floor, signaling his distress. Burwell came to the rescue and Browere began breaking the cast with a hammer and chisel, jarring the old man’s head with the knocks. Once the mask was broken off the face, some plaster still clung tenaciously to the neck, requiring the sculptor to take a knife in his powerful hands and run it between the skin and mold. The cast having fallen in pieces to the floor, Browere picked them up with satisfaction, seeing that the likeness once glued together would be good. He disregarded the stare of Burwell, who held the president in his arms and cast the plasterer a fierce look. Nine years later, when Browere was dying in New York,

a victim of the cholera outbreak of 1834, he asked that the heads of his most important plaster busts be sawed off and placed in crates for forty years. Only then would his work be revealed to a more enlightened future generation as a great achievement. He raved on his deathbed as he did even in better days, vilifying the academic art establishment that had jealously dismissed him, envious of his extraordinarily lifelike art. He hated the rumor about how he had nearly killed Thomas Jefferson, the legend that went first to the newspapers in Richmond and then to other rags across the nation. It was all a lie—the man’s life was never in danger. His enemies hated his work because it was too true.

The refined artists scorned him as not really an artist at all, just a man who coated people’s faces in goo and peeled back a perfect copy: he was a mechanic, a laborer. His studio was a “plaster factory,” as Browere himself called it, there at the corner of Center and Pearl Streets in Manhattan, not far from the home of John Quidor, his friend. They made a perfect pair, those two—Quidor with too much imagination, Browere with none—united in their pursuit of the uncouth. But there was something off-putting about his work.

Even on the best of days a whiff of death attended Browere’s art. When he rode up to a notable person’s house, it was as though the undertaker himself had arrived. With his plaster and chisel, he might as well have been measuring coffins; his presence was a sure sign that his subject was not long for this world. His first bust, back in 1817, had been of John Paulding, a dying hero of the Revolutionary War, one of three colonial soldiers who captured the British spy John André and sent him to the gallows. Now Browere was the executioner, the likeness-man, first taking Paulding then eventually his two colonial comrades, David Williams and Isaac Van Wert, before turning to other elderly worthies, transiting them on plaster-caked journeys to the beyond. No wonder a famous person might take fright on Browere’s approach. He would freeze you in time, turn you to tendon and bone, and suck all moral value from your speechless head. Jefferson, barely alive and almost killed in the act of commemoration, died the year after Browere’s visit. And pity the destined subject that gained the grave before Browere could arrive. He was not above exhumation.

When his busts were uncrated forty-two years after his death, displayed at the Centennial Exposition of 1876, the wrinkly replicas were less a national gallery than a sideshow, a carnival, and not a terribly beguiling one at that. They attracted only a few gawkers. In life the man had been an evil wizard, a weird force, who routinely cast “terrible imprecations upon the heads” of his enemies—curses strangely like the creepy terms of his plastered praise. The late sculptor’s son, himself an artist, bestowed the remembered sitters with posthumous togas, hoping to dignify their strangely naked shoulders, but it was no use. The pantheon was a crypt.

Strange then that Browere and Nat Turner both came within a hair’s breadth of taking the same life. Turner originally fixed the date of his insurrection as July 4, 1831, choosing it because Jefferson had died on that day five years earlier, fifty years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The deed accomplished, Turner might become a new Jefferson, author of a new declaration. By a black art he would be free, his Bible a new national creed. Jefferson would symbolically die a second time, falling in the name of the scripture he had taken to reading in his last years, when he expressed “his contempt for all moral systems compared with that of Christ.” When Turner moved back the date of the rebellion, he might still have taken solace, had he known that Browere had already scared the life out of the president, nearly suffocating him and holding a knife to his throat.

In the way of things, however, the symmetries were not so neat. Turner himself sat for a macabre and lifelike portrait, the interview of Thomas Gray, who took a “faithful record” of the prisoner’s words while he awaited death in his Virginia cell. History for Gray, no less than for Browere, was a perfect replica on the eve of death. Did anything escape this mortuary craft? Art palls, it obscures—but in that night, that tone of smoke, we hear a voice otherwise withdrawn and gone.

__________________________________

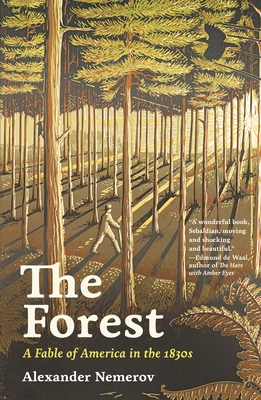

From The Forest: A Fable of America in the 1830s by Alexander Nemerov. Used with permission of the publisher, Princeton University Press. Copyright © 2023 by Alexander Nemerov.